Some nine years ago, a collection of expressive little icons — emoji ? — showed up in our smart devices and now it’s hard to imagine life without them. Everyone uses them — teenagers, adults, corporations and even large institutions like the EU. Emoji aren’t just silly icons for adding flair to our online conversations. Some argue that emoji is a “lingua franca” — a bridging language that allows us to communicate across spoken language barriers and cultural differences.

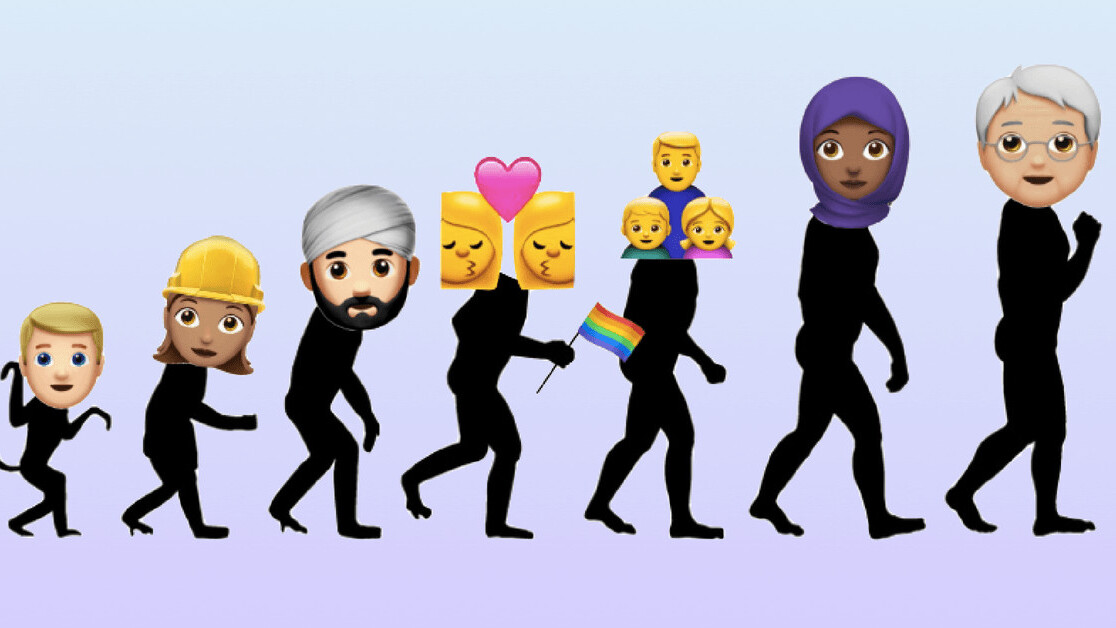

Emoji saw their virtual light of day in the year of 2010 when they became available globally. In the beginning, they might have seemed overwhelming, with a wide range of options and categories available. But after a while, the novelty wore off and people noticed that there actually weren’t that many options. In fact, emoji was lacking. People found emoji to be overwhelmingly white, a bit sexist, and, in terms of religious symbols and cultural diversity, extremely limited.

Fast forward to 2018, and you have Google promising to serve up gender-neutral variants of popular emoji in the next version of Android. A lot has happened in those eight years — those seemingly innocuous little icons have been shaped by politics and global opinion into a new language for the digital era.

Emoji: A brief history of time

Emoji were first created in 1999 by the Japanese artist Shigetaka Kurita, who wanted to create a simple, quick and attractive way of conveying information. At that time, Kurita was working as a developer for i-mode, an internet platform of Japan’s main mobile carrier, DOCOMO.

Kurita’s emoji quickly became popular in Japan, and ten years later the rest of the world followed. In 2010, the Unicode Consortium, which is responsible for the standardization of symbols in digital interfaces, adopted the emoji. All emoji that today are supported by smartphones derive from a standardized model created by the Unicode Consortium.

When Unicode first introduced support for emoji in its version 6.0 in 2010, numerous issues began to crop up: human emoji had no other skin-colors but white, the men could be seen in some different professions like a construction worker, ?♂️ police officer, ?♂️ or guard, ?♂️ while women had the only option of a bride with veil. ? Similarly, the family units were the classic nuclear version, ???? and the only “couple with heart” emoji was of a straight couple. ?

The founder of Emojipedia, Jeremy Burge, explained “This was the original emoji set compatible with phones outside of Japan. The emoji in this update were created based on what was available in Japan at the time.”

This explains the limited diversity of the original emoji set and also why there were (and still are) so many randomly specific Japanese-themed emoji, like “love hotel,” ? and “Japanese post office.” ?

Although it was rather limited, this initial release in 2010 was the start of a major change in the way people communicated on the internet. We just didn’t know it at the time.

#EmojiEthnicityUpdate and “the Great Emoji Politicization”

In 2012, pop sensation Miley Cyrus, in a tweet, called for an increase in ethnicity options in emoji, using the hashtag #EmojiEthnicityUpdate.

RT if you think there needs to be an #emojiethnicityupdate

— Miley Ray Cyrus (@MileyCyrus) 19. december 2012

This did not immediately lead to a reply from the tech industry, but it did fuel conversations online. People were increasingly starting to question the variety of emoji available and pointing out where it was lacking. Two years later, on March 24, 2014, Apple responded to the conversation:

Our emoji characters are based on the Unicode standard, which is necessary for them to be displayed properly across many platforms. There needs to be more diversity in the emoji character set, and we have been working closely with the Unicode Consortium in an effort to update the standard.

2014 became the year Wired named “The Great Emoji Politicization.” Online discussions at the time were highly focused on how emoji did — or rather didn’t — represent the vast amount of people from different cultures using them. Everything ranging from food to flags to family units was being discussed and criticized.

Emoji as a concept had evolved into a language people needed to express themselves in the digital sphere but lacked the words. Arielle Pardes from Wired, explains “It wasn’t just a matter of having the right icon to describe what you ate for lunch — it was having a digital acknowledgment of your culture.”

When Apple responded to the conversation, it probably already knew that something was in the works. On June 17, 2015, one year after their response, Unicode released version 8.0 of its standard, which, as Emojipedia’s Burge explains, “Unicode 8.0 was the first Unicode release with a focus on human diversity. This update allowed companies to support different skin tones for the human emoji.”

Emojipedia declared the year 2015 as “the year of Emoji diversity.” Every updated version of Emoji since has brought new additions to inclusive emoji. Some of the more notable inclusions are women portrayed in various professions, like “woman detective,” ?️♀️or “woman firefighter,” ??to food options representing different cultures, religious symbols like prayer beads, ? headscarves and garments, ?? synagogues, ? to single parents, ?? or same-sex couples. ?❤️? And, most recently, a gender-neutral person. ?

The politics of emoji

If emoji are to be understood as a language to express ourselves and our culture, Jeremy Burge says “It’s only reasonable that these should reflect the world around us.”

However, as emoji get more inclusive, more diverse and more ‘woke’, emoji also get political.

Representing cultural items or religious symbols in emoji is an important, but also a rather harmless step for the Unicode Consortium to take. The discussion immediately becomes more nuanced when it comes to representing nations and its flags.

When the Unicode 8.0 was announced 200 new flags were added to the emoji set – and among them was the Palestinian flag. ?? Before this update, there already was an Israeli flag. ??

The relationship between Israel and Palestine is a long-standing, brutal, geopolitical feud. Palestine is recognized as a state by some countries, but by others as ‘the Palestinian Territories’. When the Palestinian flag was added to the emoji set, and therefore also to iOS and Android, the website Geektime speculated if this could mean that tech companies are actively taking a political stand.

In that article, author Roy Latke pointed out that there has been evidence to show for this before. For example, in Apple’s iOS 6 update, Jerusalem had deliberately not been presented as the capital of Israel. Similarly, in 2014 Google changed the definitions of its search engine to show ‘Palestine’ instead of ‘the Palestinian Territories.’ It was a relatively minor change, but one that sent a powerful, symbolic message.

The Rainbow flag ?️? was added to the emoji set with iOS 10. Mathew Shurka, an LGBTQ+ activist was one of the most vocal advocates for getting the Rainbow flag added to the emoji set. In a YouTube video shot in June 2016, he urged people to sign a petition for adding the Rainbow flag emoji, arguing:

The thing about the Rainbow flag is that it’s bigger than just the LGBTQ+ community. It crosses all borders, races, genders and sexual orientation. Maybe you think emoji are silly, but they have become a part of our everyday life. It’s a form of expression and the Rainbow flag emoji would allow people to express love and acceptance.

Taking the notion about flags a bit further, in a Wired article, Collette Shade argued:

Many Kurds recognize Kurdistan as a nation, but it is not officially a state, meaning it lacks a sovereign government and international recognition as a sovereign entity. But it is possible that in the near future — due to war and disputes in Iraq — Kurdistan might become its own state. Will a Kurdish flag emoji arrive then? And, more broadly, how will Unicode deal with a world of shifting international borders?

This does raise some interesting questions in terms of how decisions are made within the Unicode Consortium. Should emoji take political situations into account or appeal to public opinion?

Lingua franca or lingua politico

Same-sex marriage is not yet legal all over the world. Similarly, the option of being registered as gender-neutral or non-binary is only available in a few countries. The official, political state of things does seemingly not stand in the way of emoji becoming increasingly diverse and inclusive.

But just because registering as gender-neutral isn’t an option in most countries, that doesn’t mean that people who identify as gender-neutral don’t exist. Just because Palestine isn’t recognized as a state by all countries, doesn’t mean that people can’t identify as Palestinian. No matter the political state of things, we need words to explain ourselves and the world around us — and emoji are words too.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.