Researchers at China’s Southwest Jiaotong University recently built a prototype for a “super maglev,” a track that carries a train at incredibly high speed using magnetic levitation (maglev). What makes it so super? According to the researchers it’ll be capable of supporting speeds up to 1000 km/h (600 MPH). That’s fast — in fact, it’s hyperloop-fast.

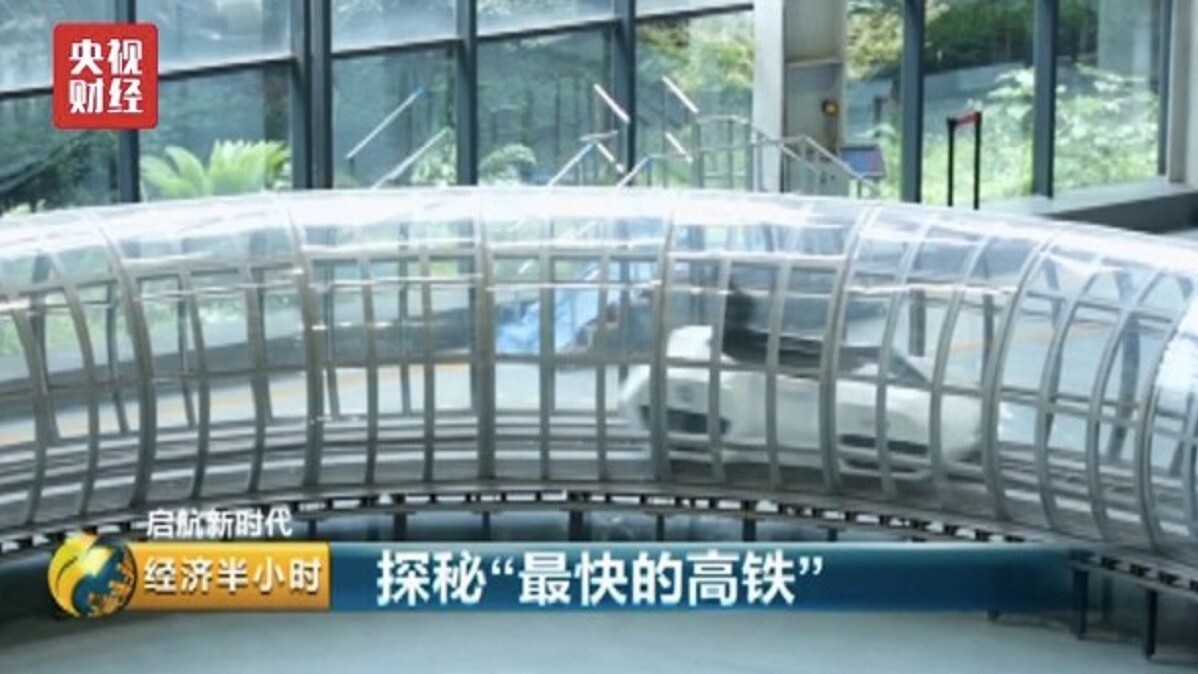

It’s the first high-temperature superconducting maglev test loop in China, according to local news site People’s Daily. The test track, a 45-meter loop, can handle up to 1,000 kilograms which is levitated over 20 millimeters above the track.

The researchers intend to build out the test track (or loop if you prefer) to send trains hurtling across China at near subsonic speeds. If successful, the super maglev would blow the current fastest train in the world, the Shanghai Maglev Train (431 km/h), out of the running.

And at ‘just’ 431 km/h, the Shanghai Maglev is a pretty intense ride:

It’s impossible to talk about the “super” maglev without talking about the “hyper” loop. Essentially, they’re using the same (or at least incredibly similar) technology to accomplish identical goals. Perhaps the biggest difference is the current status of the projects.

The Chinese effort appears to be focused on building tubes above the ground and has currently been tested in a relatively small closed-circuit at speeds up to 50 km/h.

Whereas, as we’ve reported, Virgin Hyperloop One’s test runs have yielded speeds of 308 k/mh and Elon Musk’s Boring Company’s have so far reached 324 km/h.

Whether above ground or under, there’s still a myriad of problems for researchers to work out no matter what side of the globe they’re on. While Musk says his company has permission to break ground for a Washington DC to New York City loop, his technology is still in the testing phase, as is Virgin Hyperloop One’s.

And the Chinese super maglev will have to solve some fundamental problems before it can scale to speeds as high as the hyperloop pods currently reach.

Sun Zhang, a railway expert and professor at Shanghai Tongji University, told the Global Times:

The train has to be able to stop whenever needed. It can be achieved in the open air using air resistance, but could it be an issue in a vacuum tube where no resistance exists? What if the tube breaks and air enters the system? That could be another problem.

Whether or not researchers will be able to overcome these obstacles in a meaningful way remains to be seen, but we’re excited for the future of transportation around the globe.

The Next Web’s 2018 conference is just a few months away, and it’ll be ??. Find out all about our tracks here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.