Some might argue that Middle Eastern culture, with its more conservative approach simply does not lend itself to the vast openness that is the World Wide Web. Examples exist of social networks, websites and online communities that aim to provide not only an Arabic interface where Middle Easterners can feel more at home in their native language, but also to provide the key elements of Middle Eastern culture. Those key elements are all based on the idea that Middle Eastern culture is inherently conservative.

This concept is a landmine-filled argument because it is built on the assumption that Middle Eastern culture can be narrowed down to a very specific definition. Taking a quick glance at cultures around the region, from Morocco to Saudi Arabia, it is clear that there is no one way to define Middle Eastern society.

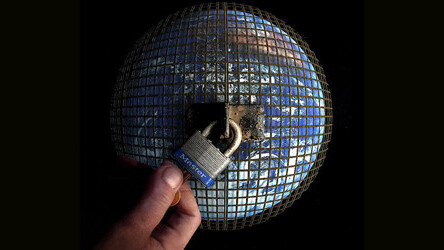

Nonetheless, there are vocal advocates in the region for a conservative web. Religion, family values, politics, privacy concerns and wariness of the foreign world are all crammed into one article that conveys the notion that the Middle East is to be treated like a bubble that needs protecting. In the face of a movement across the Middle East which is slowly breaking down stereotypes that have metaphorically been set in stone, this argument sounds dated.

The idea that a Middle Eastern audience needs censorship does nothing but take us one step back. Taking a look at YouTube’s most favourited videos for a localised Egyptian audience shows there is an extremely mixed collection of videos that cover an entire spectrum of topics, from politics to football, from religion to pop culture. That list of 20 videos is an excellent representation of Egyptian culture, which cannot be pigeon-holed. And this can be applied to any country throughout the Middle East. In fact, when YouTube first launched its localized versions for eight Middle Eastern countries, the word ‘sex’ appeared in 2 out of 20 of the most viewed videos of all time in Egypt.

If you were to take a look at some of the most popular sites in the Middle East according to Alexa, you’ll find that usage in the region doesn’t stray too far from the rest of the world. In Saudi Arabia, YouTube and Facebook are the second and third most visited sites, with Maktoob coming in sixth. In Egypt, Facebook claims the number one spot, with Arabic sites Fatakat and Maktoob claiming the eight and ninth position respectively. This pattern dominates across the board in all Middle Eastern countries, where the most popular sites include Google, Facebook, YouTube and Maktoob, with a few localized news, football and social sites making it into each country’s list.

Despite Facebook’s popularity with the online Middle Eastern community, there are some who might shy away from the social networking site. Facebook has come under constant criticism for what has been labeled an anti-Muslim stance, and the rise of Muslim-specific social networks seems to be, in large part, a direct response to its policies. 2.5 million Muslims reportedly threatened to quit Facebook when some of their pages were deleted including, I Love Mohammed and Quran Lovers, while Facebook simultaneously allowed for anti-Muslim pages such as Everybody Draw Mohammed Day.

An obvious example of a Facebook-alternative for the Middle East’s Muslim Internet users is IkhwanBook, launched by Egypt’s organisation, the Muslim Brotherhood. The conservative social network, which ironically has a page on Facebook, labels itself as a social network which offers users “a decent social environment,” promoting “moral values.”

But a quick look at the figures on Middle Eastern members on Facebook shows not only a staggering 27 million users, it also shows that this number has almost doubled in just a year. If that trend is anything to go by, it’s obvious that Middle Eastern users want exactly the same thing as the rest of the world.

That said, there is an undeniable need to translate the web, and to offer content in Arabic. Middle Eastern developers are very aware of that. The very existence of a service like Yamli, along with Arabic content providers such as Istikana and Mawaly proves that Internet users in the Middle East want access to content in their mother tongue, just as is the case for any other foreign language speaker throughout the world.

With language, as with everything else,there is no steadfast rule as far as a Middle Eastern audience is concerned. Taking Facebook usage as an example, 91% of Lebanon’s Facebook users opt for the English interface, while 67% of Palestinian and 60% of Saudi Arabian Facebook users prefer Arabic. Other countries such as Egypt, Jordan, Libya and Iraq are evenly split between the Arabic and English interface.

These statistics alone are representative of the fact that there is no one easy or convenient label for the Middle Eastern Internet user, and anyone who attempts to stamp, seal and deliver the entire region’s online community under one banner, will be hard pressed to find evidence that backs that argument.

Yes, the Middle East needs sites like d1g.com and Ikbis where users can find almost exclusively Arabic content, but does the Middle East need to be told what content not to access? I have my doubts.

Middle Eastern governments, as well as worldwide software companies, are hard at work in their attempt to censor and limit access to the Internet in the Middle East. In the process, perfectly innocent content is blocked, and the fundamentals of human rights are abused, since Internet access was declared a basic human right. It is a sad reality when bloggers or programmers take it upon themselves to actively participate with self-censorship.

The sites and online services that emerge from the region aim to offer an all encompassing experience and there is an amazing opportunity to give audiences the best of both worlds. The thought that Arabs are not ready for an unrestricted online experience does not give programmers or end users the credit that they deserve. And when approaching a scene with so much potential and space for development, there is something to be said for doing so in the spirit of openness and freedom making its way through the Middle East.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.