The 10-Year Challenge was the year’s first big internet fad. You remember? When people posted pictures of themselves from 2009 and 2019 in order to… well, actually, that was it. Depending on who you talk to, it was either a benign trend for people to show off how resilient their faces were against the tides of time, or a conspiracy by Facebook to improve its facial recognition tech.

Whatever it was, it came and went. But there was one late entry to the short-lived trend that was of particular interest, due to its connection with hypocritical internet policies and disinformation: this tweet by former Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Finally did the #10yearchallenge pic.twitter.com/LvyfVEhlOG

— Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (@Ahmadinejad1956) February 25, 2019

If we look past why Ahmadinejad picked a picture which shows him squinting — and the fact that he used two different fonts for 2009 and 2019 — it’s a pretty standard example of a politician trying to hop on online trends to impress the youths, right? Kind of, except that Ahmadinejad was the one who banned Twitter in Iran back in 2009 — and it’s still inaccessible to Iranians today.

In addition to being hypocritical, this encapsulates the Iranian government’s use of the internet, according to Emerson Brooking. He’s the co-author of LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media and a Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, an organization that focuses on tracking, identifying, and bringing attention to disinformation campaigns around the world.

“It’s so surreal to see a former president — who might have future political ambitions — participating in this light-hearted challenge, on a platform that he himself oversaw the ban of in the aftermath of the Green Revolution,” Brookins explains. “He jailed people for years for using this platform. Now he’s using it, even though the law hasn’t changed.”

Yup, you read that correctly. Ahmadinejad (which Emerson pronounced perfectly, while I butchered it every single time) banned the platform when protestors used it against him, and then he joined it in 2017 — before his aborted presidential bid — to woo voters who weren’t allowed to use the platform. Sounds confusing and contradictory? That’s because it is.

The forgotten front: Iranian influence operations

Brooking has studied Iran’s disinformation campaigns — which usually are overshadowed by coverage of other countries like Russia — and how the government conducts information warfare. To him, this tweet underpins the state’s seemingly paradoxical approach to social media.

During his talk at the DisinfoLab Conference in Brussels last month, Brooking laid out how the Iranian government views the internet as a threat to its rule, but at the same time recognizes its capabilities to influence citizens of other countries.

“Iran clearly sees platforms like Twitter as a threat after 2009, but this conceptualization kind of exists on a spectrum. Iran also understands that in order to assert its place in the world, and to realize its foreign policy objectives, it has to use these tools — which are also verboten if you’re a member of the Iranian public,” Brooking told TNW.

So what exactly are the possibilities Iran sees? Disinformation.

Information warfare can lead to real-world damage

A couple of years ago, Pakistan’s Defense Minister was duped by fake news, which is suspected to have been a part of an Iranian disinformation campaign. The story featured made-up quotes by the Israeli Defense Minister in which he supposedly threatened to “destroy” Pakistan. The Pakistani minister took to Twitter (again weird, remember it’s banned in Iran) to declare Pakistan was also a nuclear state, insinuating severe retaliation.

Luckily, it didn’t escalate any further, as the Israeli Ministry of Defense was quick to point out the original interview was complete fabrication, and the Pakistani minister backtracked.

But what this shows is disinformation doesn’t always have to just be about swaying the public. And even though Iran’s disinformation is generally easier to spot than Russia’s, it doesn’t mean it doesn’t work.

This is a huge concern says Brooking, as the current US President is “uniquely susceptible to disinformation and misinformation of all sorts.”

Although Putin and his cronies are the biggest and likely the most successful players in information warfare — as well as ones that hog the headlines — there are currently around 48 countries that conduct formally organized social media manipulation campaigns within and beyond their borders.

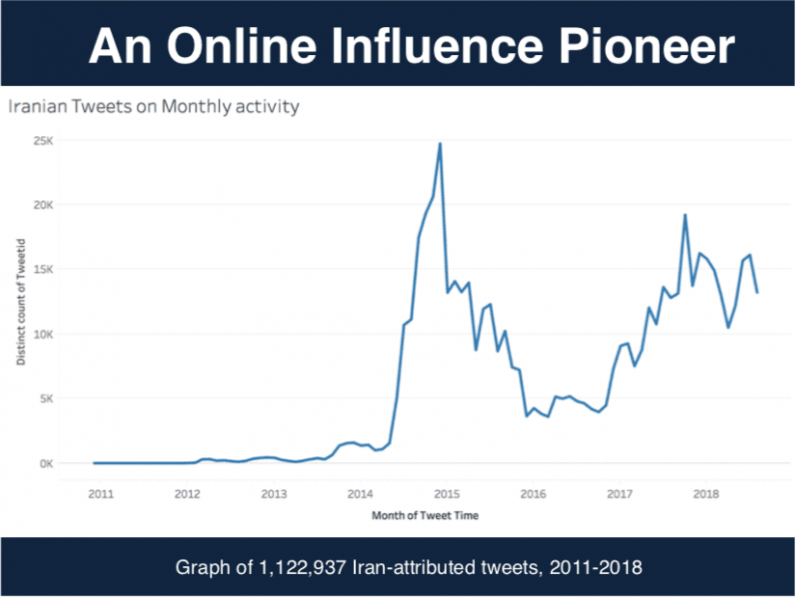

Iran started waging information warfare several years ago, and there are now around 1,300 Facebook ‘assets,’ 300 Instagram accounts, and over 3,000 Twitter accounts attributed to the Iranian government. These numbers are small compared to Russia’s disinformation efforts, but enough to make an impact where it matters for Iran.

Iran has used these inauthentic accounts to push disinformation that’s in line with the government’s ideological beliefs and to help it achieve its global policy objectives. The biggest targets have been Indonesia, and countries with dispossessed Muslim minorities like India and Nigeria.

“Iran’s goals are quite straightforward: remain the leader of Shias in the world, and try to be a counterweight to Saudi Arabia when it comes to be the leader of the Muslim world. Generally promoting anti-Israeli and anti-US narratives,” says Brooking. “They frequently deal in outright falsehoods, but their falsehood aligns with their worldview and you can generally predict the sort of disinformation Iran would engage in.”

If there’s a lesson to be drawn from this, it’s that disinformation goes way beyond the well-known US-Russia axis. Even though Russia’s disinformation is a whole other level of threat — sowing nuanced disunity, rather than advocating a certain position — we have to be aware of other active state-run campaigns. After all, they might still sway people in power.

.@DFRLab‘s @etbrooking concluding that #Iran is an (often overlooked!) early adopter of digital information warfare, a #disinformation pioneer just as #Russia is, as – unsurprisingly – both states can be defined the same way. #Disinfo2019 pic.twitter.com/PFpwnvAhbP

— Martin Mycielski???? #FBPE #FBR #Resist (@mycielski) May 28, 2019

What can be done about it?

Brooking wants to clarify, however, that talking about Iranian disinformation isn’t meant to stoke fears or drive hysteria. The best defense for internet users is simply to know it exists and how it works. Basically, it needs to be discussed in a public setting.

While this is the part citizens can play, governments and companies need to step up their actions against disinformation campaigns. That includes recognizing the problem and building up digital resilience. This has to happen sooner rather than later, as the problem isn’t going away; the playbook that’s been pioneered by actors like Russia and Iran has been exported to the rest of the world.

“Speaking from a US perspective, I’m elated by the steps that Europe’s taken recently, both France and Britain have amazing new regulatory frameworks out, which pursue potential ways to regulate these platforms and have more government insight into these information challenges,” says Brooking. “But I’m alarmed at the lack of governmental emphasis on these challenges at home. So my intent in the long run is to catch the US up to the position Europe is in now.”

Let’s hope the next time Ahmadinejad participates in a 10-Year Challenge in 2029, the problem of disinformation will be long gone.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.