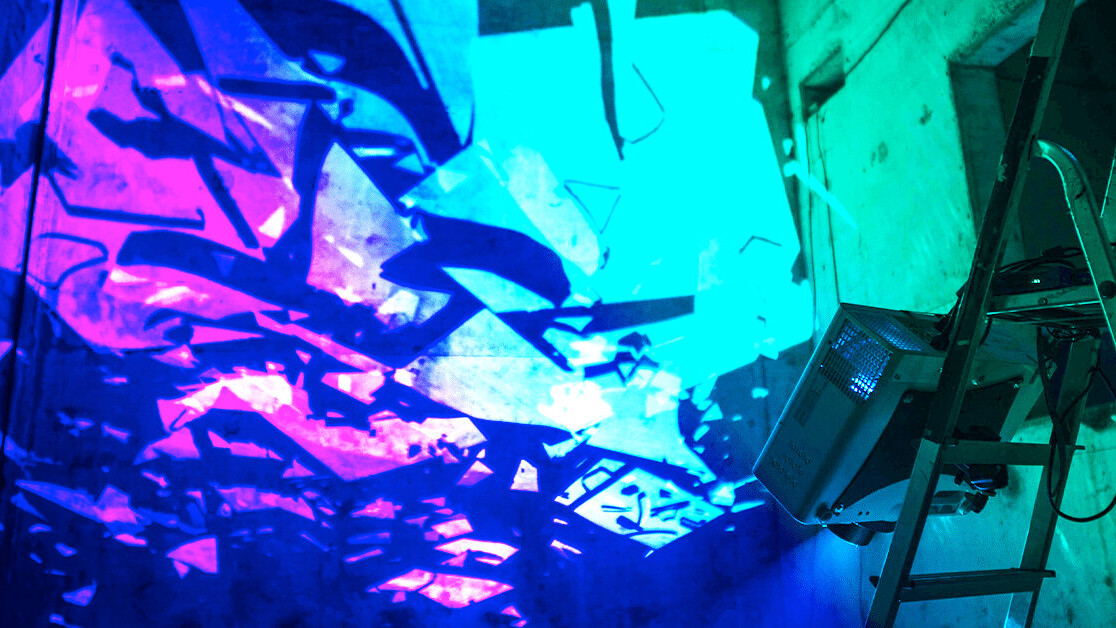

In early May, an image of hope glowed from a downtown Seattle office building. Urban artist Karl Read projected The DREAMER, an illumination of a flying boy, to praise health carers and essential workers around the globe.

Projection art has come a long way since the earliest projectors, or “magic lanterns,” used reflectors to project images from a glass slide to a surface.

One of the first signs of video mapping (or projection mapping) came in 1969, when a projector illuminated irregular objects and surfaces. Disney Imagineer Yale Gracey created the optical illusions — which included five singing busts otherwise known as the ‘Grim Grinning Ghosts’ — via a 16-mm film projection for the opening of Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion ride.

The nascent art form blossomed in the 2000s when projection technology became more affordable. One of the earliest adopters was the conceptual artist Jenny Holzer, who has been projecting messages about gun violence, love, and forgiveness on buildings and landscapes since 1991.

Over the past few months, artists, activists, and communities have superimposed digital images on building facades and landscapes to create uplifting moments of hope during these surreal times.

Projecting hope

Projection technology has been used since the start of the crisis in January. The Chinese city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, projected the giant, illuminated words “Go Wuhan” onto the sky-high buildings, encouraging residents to keep their faith.

To celebrate the end of their 76-day lockdown in April, LED units created a magnificent light show, projecting images of health workers all over the city.

The city of Wuhan’s gesture ignited a wave of supportive messages across famous global landmarks, from “Stay Home” projected on the Great Pyramids of Giza in Egypt, to the short and polite “Merci” illuminating the Eiffel Tower for French healthcare workers.

“Thank you to our community heroes” appeared on the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the largest building in the world. In Rio De Janeiro, the iconic statue of Christ the Redeemer shone bright to honor the Brazilian healthcare workers with the quote “Pray Together” projected in different languages on its body.

In “a sign of hope and solidarity,” the Swiss light artist Gerry Hofstetter lit up the famous Matterhorn mountain located on the Italian-Swiss border that peaks at 4478 meters.

Iran showed support by digitally draping Tehran’s Azadi (Freedom) Tower in flags and messages of hope and solidarity, and the rainbow became a Canadian symbol of hope in Montréal, projected on landmarks and bridges, accompanied by the quote “Ca Va Bien Aller,” or “It will be ok.”

Projecting reality

Digital projection is also being used to help people understand the raw reality of the pandemic.

In Washington D.C., as a part of the COVID Memorial initiative, visual artist Robin Bell created a digital archive of photos and messages from people who lost loved ones to COVID-19, which were projected onto building facades across the country. During a vigil in New York, nonprofit grassroots organization NICE used projections to spotlight the undocumented (and underserved) immigrant workers providing essential services.

Globally, artists have embraced the medium to spread messages of light during the pandemic. The dance collective Urbanity Dance gave residents in various neighborhoods in Boston momentary relief with pop-up projected art and dance videos. In Israel, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art created the project “Through a Balcony” — featuring Israeli artists whose work deals with subjects such as “the position of the human body in relation to the political and the personal” — to project video art onto the walls of buildings.

The artwork of muralists, street artists, and visual artists such as Shepard Fairey, Bunnie Reiss, Rebecca Elise Cook, and Molly Crabapple illuminated numerous building facades and walls across the United States. Messages of appreciation to the medical community were projected on two New York City hospitals by the Seattle design lab Amplifier.

In the UK, to show appreciation for the British National Health Service, carers and health workers reached dazzling heights with the clapping hands animation, created by British textile artist Ian Berry. The animation has since also been shown in Sweden, Mexico, and the United States.

Projecting change

Projections are also an attention-grabbing form of protest — and quite frankly the only option in most places as the lockdown limits in-person demonstrations. A protest message shown in a large-scale projection can heighten awareness, open dialogue, and bring immediate public attention to those in need.

The art-activist collective The Illuminator has used large-scale projection interventions as its main strategy. To protest the response of the Trump administration to the pandemic, the group projected their demands onto a high rise building in Manhattan, including “CANCEL THE RENT,” “Free Care for COVID,” and “Healthcare for All”.

In Santiago, Chile the art design studio Delight Lab projected the words “Hunger” and “Humanity” on public buildings — though the effort was censored by the Chilean police. Digital art collective Projetemos in Brazil protested against the inadequate crisis response of president Bolsonaro, while Latin American art and activism collective Articiclo protested national healthcare limitations in Mexico and Argentina

While many parts of the world still remain in lockdown, some have the luxury of ordering takeout, organizing Netflix watch parties, and connecting with friends and family over Zoom. But there are many who are living in close quarters without adequate protection against the virus, and who are urgently in need of support.

Artist Hank Willis Thomas’s project “The Writing on the Wall” spotlights the struggles of those incarcerated during the pandemic. Thomas projected the messages — which were written by people in jail — onto the criminal justice buildings in downtown Manhattan.

Bringing communities together

Projection technology can create immediate reminders to the public about the rise of inequality during the pandemic.

The resurgence of community spirit has shown people can — and will — come together to offer each other support during the crisis. Viral videos show films being projected onto neighborhood walls to keep inhabitants entertained, especially in countries where restrictions are strictest.

The Italian organization Alice nella Città inspired people to project movies onto their neighboring buildings. Soon classic films such as Dead Poets Society and La Dolce Vita brought a moment of joy when they were projected in the cities of Rome, Palermo, and Turin.

Similar projects took place in Berlin, Paris, Bogotá, Madrid, Rio de Janeiro, and Cork, Ireland.

My neighbour @scottduggan had the most beautiful idea to project classic movies for our terrace, listening to the movie on an FM signal sitting in our own separate front gardens made us all feel a little less alone :) donations went to @AgeAction pic.twitter.com/8lhEnYW21l

— Clare Keogh (@claremkeogh) April 8, 2020

In these turbulent and uncertain times, daily reality is changing our definitions of connection and distance. And while technology can be used for divisiveness, it can also be a tool to spread hope, protest, and build communities, even when the world is stuck inside.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.