Through the centuries, China’s entrepreneurs accessed finance from family and friends through social networks known as guanxi. Even after the communist revolution, these networks helped to propagate a thriving small business sector that invested in local services and basic manufactured goods.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, when President Deng Xiaoping started to open up the economy, it didn’t take long to rekindle the innate entrepreneurial spirit that saw China’s traders conquer the old Silk Road. Following the ascendance of tech juggernauts Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu, coupled with later market liberalizations, there has been an explosion of both local and western venture capitalists eager to find the next generation of Chinese unicorns.

China now has the largest venture capital market in Asia, second only to the US worldwide. This is all the more extraordinary given that the communist Chinese constitution did not formally recognize the legitimacy of private enterprise until 1988.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, this vitally important source of finance for entrepreneurs was always likely to be under serious threat. Unlike banks, which can make decisions about business lending using automated credit scoring, venture capitalists and angel investors rely on meeting entrepreneurs face to face to judge whether their start-ups are investable.

Because China was the first country to be adversely affected by COVID-19, we decided to examine how this sector has been affected. This, we hoped, would help gauge what is likely to be happening to other economies now in economic meltdown. The results are not pretty.

What we found

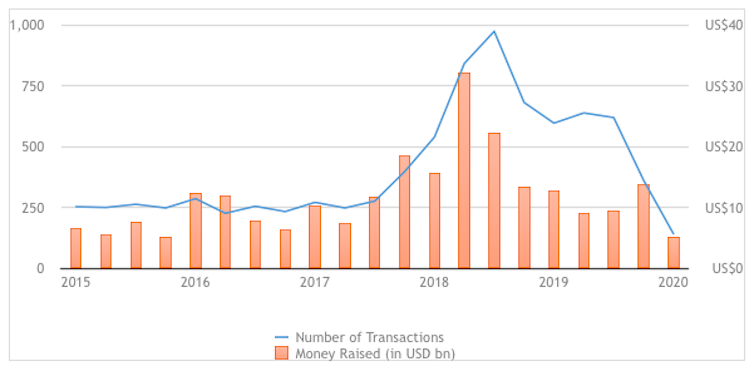

We discovered that since the outbreak of the coronavirus in China, there has been a dramatic decrease in aggregate levels of investors taking stakes in new businesses. Across the full spectrum of venture capital, from investments in brand new companies to those that are already profitable, we found a 60% decline in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019.

To put this into perspective, this is three times the size of the decrease during the global financial crisis of 2007-09. Some estimate that if a drop like this were to happen globally, approximately US$28 billion (£23 billion) in start-up funding could be lost.

When we looked at seed-stage investments – those typically dominated by the smallest and youngest start-ups – they almost totally disappeared in China during the first quarter of the year. There were fewer than 20 deals in total, representing an 86% reduction year on year. In other words, start-ups during this crisis have been all but starved of new finance.

China seed-stage funding 2015-20

The sectors that benefit most from seed funding in China are education, e-commerce, media and entertainment, healthcare and AI/robotics. Most of the money comes from local Chinese investors, and this is probably a good barometer of the areas of the economy worst affected by the crisis – education and entertainment above all.

In contrast, larger later-stage venture capital deals are being less adversely affected. This may be because many deals are funded by investors that are foreign-owned, often from places only hit by the pandemic later in the quarter. Significant foreign-owned investors include Sequoia of the US, Japan’s Softbank and the UK’s Baillie Gifford, as well as sovereign funds like the Qatar Investment Authority.

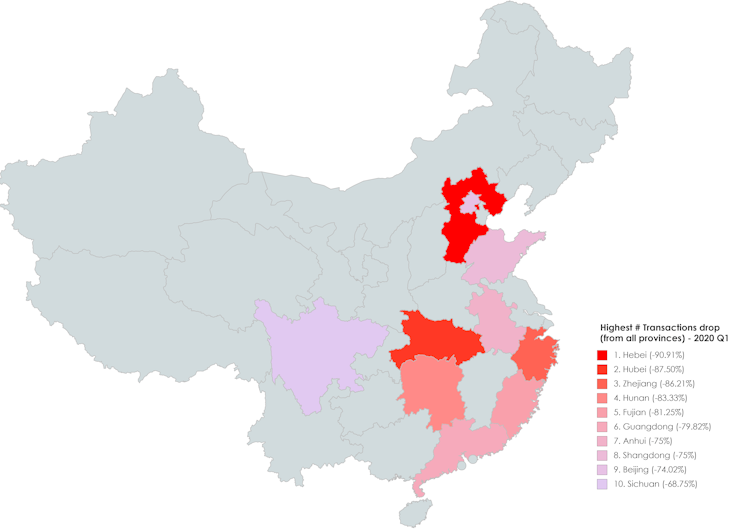

We also examined which areas in China were most negatively affected. Traditionally, entrepreneurial finance was concentrated in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzen, though in recent years, investors spread their nets across the country. Now, however, there appears to be a worrying retrenchment. Some provinces seeing the greatest decreases in investment are the same ones worst affected by the virus – Hubei, Zhejian and Hunan.

Worst affected provinces, Q1 2020 vs Q1 2019

The UK situation

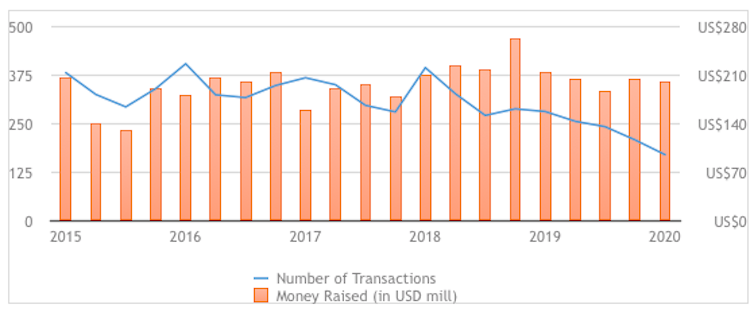

The UK relies more on venture capital than most European countries, so our Chinese data begs important questions about what is happening closer to home. From our analysis, we detect a marked drop in entrepreneurial finance in the first quarter of 2020. Like China, the youngest and smallest start-ups are the ones most affected by the crisis, though other stages of the investment process have been hit too.

UK seed funding, 2015-20

From the chart above, the number of seed-funding transactions in the UK actually halved between the first quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2020. It could be that this was initially due to uncertainties caused by Brexit, then accentuated by the pandemic.

We can safely assume that the figures for the second quarter of 2020 will show further dramatic declines. The uncertainty suffocating entrepreneurial activity in the UK has already had a massive impact on the economy. Early figures show that the number of firms going bankrupt in March was 70% higher than the same month last year, while registrations of start-ups fell by a quarter. Clearly this crisis is unlike any in modern times.

The UK government has just launched a suite of support packages including the £500 million Future Fund and a £750 million fund to target support for innovative small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Importantly, these schemes depend on co-investments between the private sector and the public sector, which may mitigate the declines in private equity investment. But as long as venture capitalists and business angels are unable to physically meet up with entrepreneurs, this kind of finance is likely to continue to be thin on the ground.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation by Ross Brown, Professor in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Finance, University of St Andrews and Augusto Rocha, Research Fellow in Entrepreneurship and Technology Exploitation, University of St Andrews under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.