NewDealDesign, the creative hub behind some extremely famous products — FitBit fitness trackers, Lytro cameras, Project Ara, among others, looks from the exterior, like a typical design firm, nestled unobtrusively in the heart of San Francisco’s financial district. But tucked behind a nondescript entrance and up a flight of stairs, the world opens up into a playground of strategically arranged objects.

These are not decorations, but accomplishments — each representing a product created by the company under the leadership of its co-founder, Gadi Amit. The entrance is uncluttered — showing each piece to its unique advantage. But soon visitors will hit a point where they can’t go any further — at least not without signing a non-disclosure agreement.

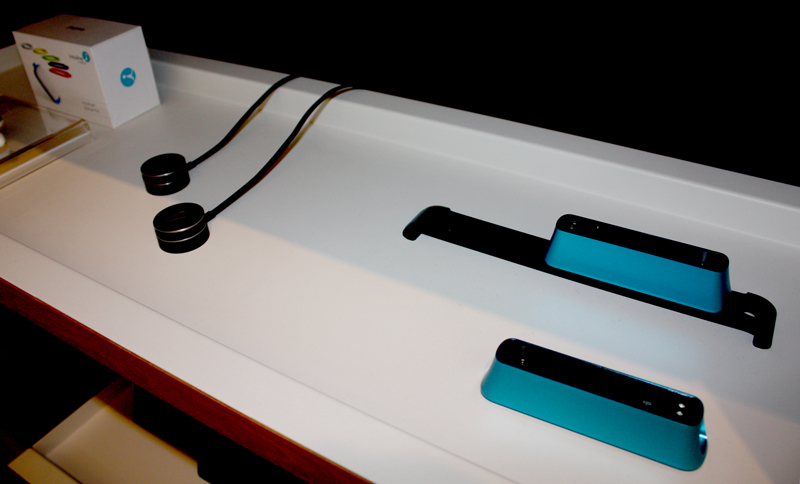

As you walk, peering surreptitiously to the part of the office where the real work takes place, things are not quite as picture perfect. A ‘War Room’ lies just beyond the field of vision, where Amit and his team wrestle live projects into submission — assembling prototypes and testing designs — visualizing what a final product may, sort of, eventually, look and feel like.

Amit has been called many things: In 2010, he was a Fast Company Master of Design; in 2014, he made it onto that magazine’s list of 1000 Most Creative People in the Business; in 2015 he was part of Surface Magazine’s Power 100.

NewDealDesign has also gotten an abundant share of recognition, including the Cooper Hewitt National Design Award, multiple Industrial Designer Excellence Awards (IDEA), RedDot, iF, G-mark, Good Design, Fast Company Innovation By Design and many other awards.

That recognition takes into account a long roster of famous projects, including the Palm Zire, the Slingbox 700U media streamer, Dell’s Inspiron notebook, the Netgear router, the Whistle health tracker for dogs, the interactive Sifteo Cubes game and more.

But how does NDD conceptualize a product and build it from the imagination? TNW had a chance to pose that question — and others to Amit one afternoon.

Let’s start with the quintessential Don Draper Question. How do you do it? How do you think?

Gadi Amit: There are a lot of cerebral, analytical data gathering background materials that we get either from the client or we go and collect it. That’s mundane, something everyone went through in high school. The real magic is in a different type of processes where we start giving expressions of ideas, form or illustration and some of these are quite naive — like doodles and some of these are more physical involving models and mockups. We try to keep the cacophony of ideas in one room — we call it the War Room.

The notion there is that some kind of serendipity will happen where ideas and people actually mingle with each other, and that there will be a joint feeling of intuition of general direction — if we take these ideas together and maybe add a little bit, then this is a good direction. In essence, the breakthroughs are quite intuitive and reliant on serendipity and that serendipity takes into account the data points and also some of the unclear and raw ideas.

And that’s where we get to the real breakthroughs and once we get that breakthrough, it actually gets more polished and more complex. But it’s still very much the early-on intuitive vector of thought.

Does this process happen all the time?

Yes. We manage the process in order to generate these ideas and vectors of ideas, and it’s a very delicate balance between thoughtfulness, analytical and the real artistic ideas. For example: Lytro. The whole notion of forgoing the traditional camera format and focusing on something we called scope, came from a discussion with Ren Ng [Lytro founder] and we talked about the human gesture of scoping something with your hand.

It had a little bit of a parallax effect, and that is exactly what the Lytro technology does. I took this to the team in the room and it was at first quite controversial. But at one point, one designer placed a mockup which was more squares, but it was clear.

We still had one or two ideas that were more traditional, but that was an exceptionally posited idea in the sense that it actually had a very good reason internally as far as the optics, good usability and very good symbolism and iconic value. In retrospect, I can actually analyze why it was good at that time, but it was purely intuitive — the notion that this is a very good idea and that this is the one.

How do you know when something is good — is the one?

Good question. My dad is a retired architect and also a musician. In music there’s this term called Absolute Pitch, where you know the note is in the right tune and a melody or harmony is there. It’s the talent of good designers to know their gut. This is a really good idea — maybe not the best idea there or the winner in the market or business — but the gut feeling of the value of an idea.

It’s very much along the lines of music. You need to feel it. And that’s a very difficult proposition in Silicon Valley and in the business world. A lot of critical decisions are going to this very uncharted and personal space. It’s the talent of a designer — like a musician — to know whether the next form is a hit or not.

What I’m hearing is that it depends on how much the client trusts you. There’s an interpersonal part to that, right?

There’s a lot of discussion around design thinking and design processes that are kind of standoffish and we are trying to create a more intimate dialog between key stakeholders — to use the vernacular — to really understand each other’s different ideas and difference philosophies.

With Lytro, I had a very good connection with Ren, and with James and Eric, the founders of at FitBit. The intimacy of this dialog is establishing not only trust but a good vibe — again, like music. There are different players but they play the same tune and they throw out ideas and they play together. Fostering this dialog is important.

How did your parents’ architecture profession influence your decision to become a designer, and how does that influence you today?

I was born with either the genetic or the environmental background to deal with design. But interestingly enough my mom was encouraging me not to be a designer. She felt it was very hard both emotionally and financially. I was a bona fide geek thoughout high school. I was good at math, physics and chemistry, and for awhile I thought I’d be an engineer or scientist.

But in my early 20s I had some time. I grew up in Israel so we have army service, which takes you away from the rush to career, and that was a very good time for reflection. At the end of that service, I had a girlfriend who had a roommate who was an industrial designer and I remember that decision was very intuitive — I want to do that. By then all my high school grooming — which was more analytical and more technical and more geek — was thrown away and I was thrown back into the creative world.

Was it thrown away? It seems to me that you are a technology designer, someone with a specialty.

It’s still there. It became a good balance. I went to a school that was very artistic. My approach toward technology projects is architectural rather than expertise or form-giving, definitely trying to get the logic and rational side as well as jumping on the outside to see where that form may lead to.

I’m oscillating between inside and outside in the design process, and this is how we do things here at the studio. A lot of the work here — whether it’s the first Lytro or the Fit Bit or Project Ara — had quite a lot of meddling with core electronic layouts and physical aspects of how the object is put together. That is somewhat challenging for the engineers and executives that work with us.

We mess with things that they typically don’t expect designers to do. They expect designers to cover nicely and stylize externally what they already had in mind. We are different than the traditional industrial designers. Instead of just giving us a layout and having us work around it, we actually go into the core function, the core architecture of the product, and there we find usability and functional efficiency and beauty — not just aesthetics.

People think of design as something aesthetically pleasing, but how much influence do you have in the product itself?

The ideas start off being very fuzzy and general. How about a pedometer that’s connected to the Internet? What is the physicality of light field technology? The assumption was that it would be a camera. We tend to ask a lot of cultural, marketing differentiation questions. We influence directly with concrete suggestions but also indirectly by fostering introspective dialog that forces the client into thinking about paradigms.

It’s not only the high-level conceptual, philosophical question. There are a lot of core issues like production technology, availability of components, cost and time to market. We navigate within this three dimensional state quite easily and I credit myself and the team here for being able to create really good, well-substantiated alternative points of view. We can think about an iconic design, but until we put it into form — and color and hold it — we cannot ascertain how valuable or good or bad it is.

So you need to prototype. You do that here?

Yes. Some of these mockups are very raw and naive. It could be a piece of foam that was folded and held with masking tape; these are very effective. There is an importance for the cadence — how quickly can you articulate ideas? So processes like 3D printing are ineffective.

Of all of the famous projects you’ve worked on, which one has been your favorite and the most influential?

FitBit may have had the most societal impact and the biggest success going from zero to an IPO; that was successful not so long ago. It’s an exceptional credential. But on a personal level, one of the most palpable moments is a completely different story. Over 15 years ago, I was working on a line of blenders for a poster and I found myself in New York, in SOHO, and they have this farmer’s market and somehow natural juices was the big thing.

So you walk through the whole street — I think it was Spring Street — and there are a dozen juice vendors and they are all using my blender. We (designers) really get a kick out of people using our stuff. This is the most delightful moment when you see it, even if it’s the most mundane object like a blender. Plenty of work went into that.

What is the biggest challenge facing the design industry today?

The biggest challenge is the misconception of what it is and what is its value. There are misconceptions about management design processes, the vetting process and the place of the designer in the whole technology role of decision making.

Typically, the technology role will see the designer as part of the execution chain rather than the conception and the strategy chain, and that’s a fundamental difference.

So designers are seen as the one that makes it look nice as opposed to conceptualizing the form and function of the product?

The fundamental difference is who tells who what to do. The engineers to the designer or the designers to the engineers.

What should it be?

It should be designers first. It’s just like architects. Because you look at the stakeholders, it comes before engineering. How does the object relate to and influence humans? It is basic in architecture and codified in law.

In the tech world it’s a rarity. I am a designer working with the technology world. I am different than they expect in many cases and there’s a process of educating clients of how to use us best and what we actually do. It’s very common for clients to come in and say we want sketches. And we have to say that before you get the sketches, we want to know what you want to do — the strategy and the goals. But they want the visuals.

People do not understand the difference between industrial design, product design and graphic design, do they?

Yeah, part of the issue with the design community is that the three-dimensional, multifaceted approach we need today to deal with complex experiences is not necessarily what the schools of design feel comfortable with. We are straddling between digital and physical on a moment-by-moment basis. That’s the reason why I call what I do technology design. I couldn’t find a different name for that. But I’m dealing with digital technology, both digital and physical, 2D and 3D, motion imagery, physical and tactile imagery.

What is the most important problem you think design has solved so far in the world?

I see problems we didn’t solve. We are at the cusp of a new era in humanity where the digital domain is really part of our personality. We have, and will have more, of a digital persona. It will become more and more a part of us.

On the medical side, we’ll have something very close to cyborgs. We’ll have artificial intelligence next to us and we’ll have a monster problem interacting, controlling and guiding that domain. This is the thing I’m losing the most sleep on.

I’m not talking about macro intergalactic problems but small issues of how do I take a medical device and make it truly easy to use, or how to deal with artificial intelligence and privacy issues. These are the concrete problems. The type of concerns I have are a bit on the back burner of some of the technologists’ field of issues.

Not even on the radar?

I want to know how could it be that no one thought about carrying an open camera attached to your head in a open bar in San Francisco.

They thought about it. They just didn’t care.

You assume they thought about it. I’m not that sure. I’ve been to meetings … [laughs]. These are the kinds of interactions that are really difficult to manage. I agree that maybe 20 years from now we’ll be less sensitive to this —but maybe more — I don’t know. But managing this transition in the next 20 to 50 years is front and center of what designers should be dealing with.

One of the things we did a few months ago was a provocative project called Project Underskin that was trying to assist in managing two things: It’s a (tattoo) implant that has a customizable user interface that’s supposed to manage your authentication and oversee some medical devices that you may have implanted in your body. That’s happening today. There will be more and more smart devices managing conditions and so on.

The notion is that you have something that is carried with you and controlled by you and gives you a glance alert without too much data.

Is that the next big thing you want to tackle?

I am taking a position that I never thought I’d have: advocacy. And I’m trying to talk to two completely different communities: the designer and the entrepreneurial community. I’m puzzled and not fully resolved that this is what I want to do but the position of advocacy is something that five years ago I could not have imagined I’d do.

We are working on a variety of projects in the medical domain and the consumer domain and trying to create meaningful interactions. The medical domain has a lot of rigid, entrenched positions that are in many cases justifiable but not entirely, so it’s a case-by-case.

And a third area is dealing with the emergence of artificial intelligence and interfaces associated with that — a lot of voice recognition, expert systems and so on. How do you manage it in a group of people? These are pretty difficult topics.

So your orientation today is, how does all this affect individuals?

There’s a tendency to view it as either individual or large society. We are individuals but we have something happening together. We’re social animals in small groups. I’m not talking about the crowd, I’m talking about the family. These are interactions that are not discussed in public. Typically, we refer to the users or the community, which is kind of an amorphous crowd. But no one speaks about the family, the couple.

There is human behavior that is more communal than one and less communal than many and it is the most meaningful interaction we have. The whole space of technology today is not set for that. You sitting here talking to me. The dumb thing that is called [Apple] Siri could not understand that you and I are having a conversation. People understand contact immediately. It’s not that difficult to program it, by the way, because the pattern of exchange between you and I is very predictable. And when [a third person] comes into the discussion, she understands the right cue to interject.

What areas of design do you think are going to be most effective in changing people’s lives for the better?

What I call technology design is probably the greatest challenge and the greatest benefit. I don’t think that creating a beautiful chair will do anything to change the world. And I’m also not subscribing to the do-gooder sort of thing. I’m dealing with a domain that I think will influence the 7 billion people we have now on the planet: the interaction between digital technology, people and society.

This is not a little thing and the ramifications for not doing it right are horrendous. We’re doing 50 percent of what we’re supposed to be doing. I think the fundamental problem with the way the society is rigged and structured, and the speed in which the digital revolution happens, doesn’t allow our societal systems to work. So we need to be pre-emptive, not only trying to clean up after the fact.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.