No one tells you that becoming a parent means keeping a lot of dirty little secrets.

Like that time you wiped your kid’s booger on the underside of a park bench when you were out of tissues. Or that sometimes (ok, at least once a month) an entire weekend goes by without them brushing their hair.

Well, here’s another one that parents don’t like to cop to: Their kids watch a lot of digital content.

According to research presented this year at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting, 20% of the children in the study used a handheld device for an average of 28 minutes a day by their 18-month check-up, as reported by their parents.

While my kids stayed away from screens until age two, they’re now no exception.

It started when I downloaded a cute puzzle app for a road trip (here’s one of our faves), but it didn’t take many weeks before the kids were opening up the YouTube Kids app and wandering for themselves.

By the time they turned three, my kids had learned how to unlock our iPad and find the content they wanted without needing to ask.

Now my twins are nearly four years old, and the iPad is a key part of our routine. They turn it on around 6:15 every morning.

Usually, I hear a friendly chirp of tiny cartoon voices talking about how many sides a square has, or the power of teamwork when fighting crime while wearing pajamas. I tune it out until suddenly I realize I’m hearing a different kind of sound: crinkling cellophane as some faceless adult with a camera pointing at her own hands opens and plays with toys.

That’s right. Unboxing videos exist for toys.

But these aren’t Christmas-morning home videos of children’s faces filled with wonder. These are manicured nails and a soft falsetto voice narrating the contents of a specialty Play-Doh set.

Or pouring beads out of a water glass to discover a surprise toy figure buried inside.

And this baby doll one that is too horrible to describe. (For an in-depth look at how these toy videos get made and served up by YouTube’s algorithm, read this story in The Atlantic.)

All my noble dreams of raising my two daughters around wooden Montessori-approved toys and bright-red metal wagons has completely degraded. But watching someone else play with toys is where I draw the line.

“Is that a toy video?” I call warningly from across the room. Both girls suddenly jump back from the screen. “iPad picked it!” they defend.

And there it is.

The algorithm defense — essentially the modern-day equivalent of “my dog ate my homework.” Like most streaming services we’re all familiar with, YouTube Kids automatically advances from one video to the next, attempting to predict what my kids will like.

Sadly, my children have watched enough of these toy videos without me noticing that the app often jumps there. So instead of blaming each other for the video selection, my kids blame a third thing I need to discipline: the machine.

When an algorithm needs a time-out

My experience isn’t the only scenario in which an algorithm hasn’t done what a user would want.

Amazon made news before Hurricane Irma when people started seeing enormously high-priced offers for water from third-party sellers.

Normally, Amazon’s listings reward vendors offering competitive pricing, but apparently, when supplies dwindled among these more fairly priced places, the obnoxious price-gouging items naturally jumped to the top of the list.

In this case, while the Amazon algorithm might normally accomplish something good, it doesn’t actively block something bad, and that’s where I think we need to change our demands of the tech around us.

The “first, do no harm” mantra of the medical field must extend to an algorithm, which needs to be programmed or taught to recognize when something abnormal has occurred and alert an actual human accordingly.

And wouldn’t it be amazing if, impending hurricane or not, Amazon’s listing pages refused to show any product that exceeds, say, 250% of the average price listed unless the user opted in to view it after a warning that the sellers are exceeding standard market rates?

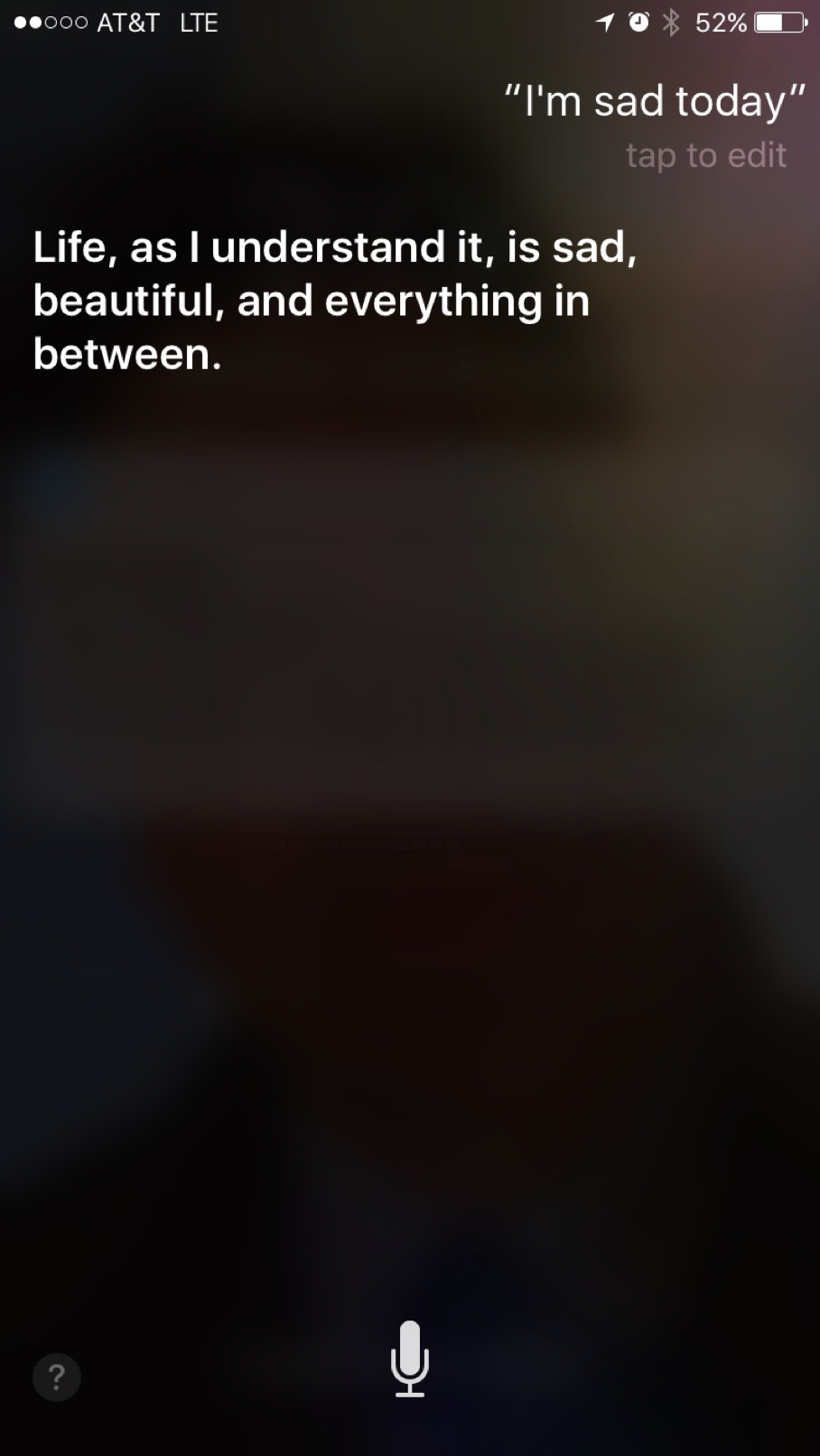

Another opportunity for “do no harm”: Apple is trying to make Siri, its voice-activated assistant, more sensitive by recruiting an engineer with a psychology background.

Apple is hiring for the role Siri Software Engineer, Health and Wellness to address in a more human way serious conversations people have with Siri — topics ranging from cancer symptoms to existential musings.

Kudos to them for realizing the need for more emotional intelligence, albeit only after the product has been in market for six years and others did research highlighting some of its gaps.

The only challenge: The job listing dreams of an engineer who has experience in peer counseling and psychology. Unsurprisingly, the opening has been active since April.

(This raises a broader question, which I won’t get into deeply here, about how our tech gets so complex that only highly technical people can build it and therefore haven’t most likely committed their lives to other things, like peer counseling and psychology.)

I certainly hope Apple is pursuing a plan B while they interview. In the interim, users should have a way to flag to Apple when a response isn’t sensitive enough. We need to crowdsource the humanity expected of these services to avoid harm.

Kids, it’s your fault, too

Back to my daily morning woes: The unfortunate reality is that the YouTube Kids algorithm is beating me.

My vigilance is flawed and easily misses when the app starts to stray into shaky territory. My daughters, sad to say, enjoy these toy videos.

They pick them without even thinking about it until I say something. That means the algorithm is getting reinforcement to continue suggesting and auto-playing this bizarre content. And the parental controls aren’t detailed enough for me to block this.

The challenge of having these “smart” devices around is communicating how they really work to young kids.

As savvy as my kids are, they still try to scroll our TV and laptop screens, because why wouldn’t they work that way too? So when it comes to explaining an algorithm in kid terms, I don’t know where to begin.

Do I ask them to imagine a “character” in the machine? Perhaps suggest that there’s a cute but fallible gremlin in there trying to help them, but sometimes that gremlin wants them to watch stuff they shouldn’t.

Or do I explain that the iPad won’t do anything they haven’t already told it they like? So it’s their fault when it auto-picks yet another toy video. I’m not sure I want my kids believing they control algorithms when too often in life, they won’t.

For the time being, my solution has been to switch to an oldie but goodie: television.

What it lacks in interactive content it makes up for by not being the content free-for-all that the Internet offers. It’s also a bigger screen, so I immediately catch when the content doesn’t meet my screen-watching standards.

Because until “smart” gets smarter, dumber is better.

This story is republished from Magenta, a publication of Huge. Follow Huge down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.