Like every child growing up in the Nineties, I spent a good chunk of my time watching the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. But in laying the foundation for being an adult geek, there was another show I liked much better.

VR Troopers was produced by Saban Entertainment, the same company behind the Power Rangers, and was made to copy a lot of the elements that made the other series a huge hit. It also featured a team of young adults trying to defeat an evil overlord by transforming into super-powered versions of themselves, but there was a big difference — they had to use virtual reality to do it.

There was a lot of excitement for virtual reality in the early Nineties, and VR Troopers tried to profit from it with the tv series and an accompanying toy line. It portrayed virtual reality as a fantastical thing — another world that you could hop in and out of. By putting on a pair of high-tech glasses, the series’ protagonists were transported to this digital dimension, where they eventually put an end to bad guy Grimlord’s rule.

The series failed to be a commercial success, but didn’t stop VR from being hyped throughout the decennium. Nintendo jumped on the bandwagon with its Virtual Boy, that promised to put the magic of virtual reality in everyone’s living room. Only being able to display extremely basic graphics that were limited to the color red, it failed to give players the immersive experience they were hoping for.

Nintendo wasn’t the only one betting on a VR future for video games. In an effort to revolutionize the arcade experience, a company called Virtuality developed a system combining plastic pods with integrated controls and VR glasses. The 3D worlds players could explore brought with them an incredibly complex control system, that didn’t work in the pick-up-and-play setting of an arcade. Only a few games were produced for the system, including a VR version of Pac-Man, which looks like the worst way to play the game ever created.

VR didn’t make it in the Nineties, mostly because the technology wasn’t there yet. The grandiose vision of an alternative reality where humans could freely roam to roam didn’t match up with the actual experiences companies were delivering. Before the end of the millennium the trend died off.

A new dream

VR spent over a decade off the radar before Palmer Luckey and Brendan Iribe started Oculus VR in 2012, and crowdfunded their concept for a new VR headset with a Kickstarter campaign. The product went through two development kits, changed its name and is now avilable as the Rift on the company’s website.

After Oculus was bought by Facebook in 2014 for a cool $2 billion, it marked the beginning of a new era for VR — one that’s decidedly more hopeful than what happened before the millennium. The headsets’s success inspired companies like HTC and Sony to come up with comparable devices, and others like Samsung and Google to utilize their existing phone ecosystem for a virtual reality experience.

Thanks to the current state of technology, wearing a VR headset like the Rift is a remarkably immersive experience. With a sufficiently powerful computer the graphics can look extremely realistic, and the headset’s trackers give the user freedom to move inside the virtual world. The VR that we know today is an enormous step up from the VR that dominated the Nineties, and instead of being used just for games, developers are coming up with other uses, too.

An example of this is Bigscreen VR, which puts you in a virtual living room to watch tv or use a computer. It might not sound terribly exciting by itself, but when other users join, it starts making sense. Together with people that might be located on the other side of the world, you can watch a movie, play games or even do some work while communicating through voice chat. It’s a mind-blowing experience that shows that VR is about much more than gaming this time around.

We’re not there yet

There’s a problem, however. Even though everything is set up for a full-scale takeover of VR, the reality is that only few people have actually tried it out for themselves. The main reason for this is that setting yourself up for the experience is very expensive.

Oculus Rift costs $699, the HTC Vive retails for $899, Playstation VR kit is $399 and all of them need additional hardware to work correctly. The Rift and Vive have to be powered by a sufficiently tricked-out computer that’ll set you back upwards of $900, and the other only works when linked to the Playstation 4, which retails for $399. If you want VR today, you either need to be ready to spend some cash or settle with the lesser experiences of phone-based devices like the Gear VR and Google Daydream.

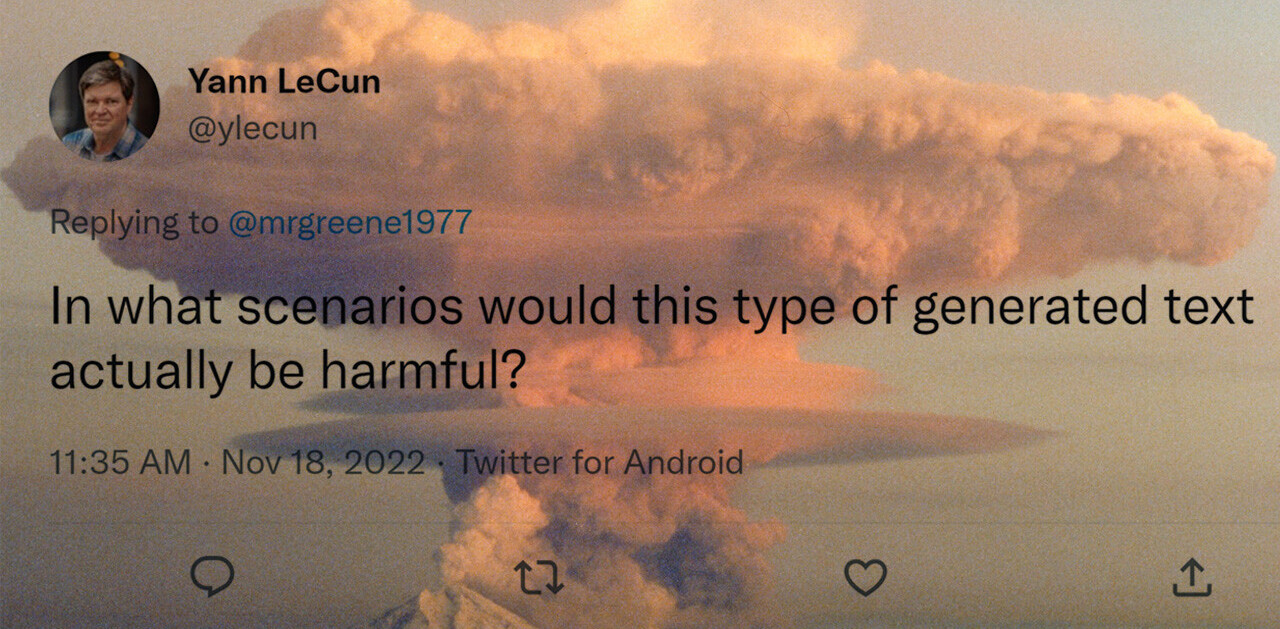

Then there are a ton of social norms to redefine. Wearing a headset makes you look strange, and as the above picture from a Samsung event in early 2016 shows, it can be pretty scary when more people do it.

2017

But it’ll only take time before we eventually catch up. A decade ago, people would give you weird looks if you would be sitting on the subway staring at a screen for the better part of the ride. Today, it’s nothing more than normal.

Initiatives like the VR Cinema in Amsterdam are slowly normalizing the antisocial connotations most people have with it by putting the technology in a social space, and it won’t take long before using VR will be just as socially accepted as checking your phone.

With three devices turned from concept to actual product in 2016, it’s been a big year for virtual reality. But 2017 is going to be important — with three big companies placing big bets on the technology, it’s sure to attract others to the space. And when more companies join, competition increases, prices go down and ultimately more people get to try out VR.

One of the most-heard complaints is that there isn’t enough great software yet. Playstation VR got a lot of criticism for its low-quality launch titles, and even though the VR development scene is more active than ever, a lot of the software stays in beta or is created by amateur developers. If bigger development studios end up creating VR content with well-known franchises and characters like Super Mario or Star Wars, it’ll be a big step for mainstream acceptance of the technology.

After such a busy year for VR, the sights are set on 2017. If the tech manages to reach critical mass, we’re only looking at the beginning of the VR Golden Age. If it won’t, the bubble will pop sooner rather than later, and history will have repeated itself.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.