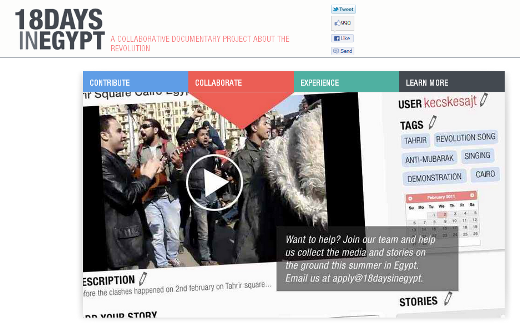

It seems that the Middle East can’t get enough of crowd sourcing, and rightfully so. The Egyptian website, 18DaysInEgypt is aiming to put together a collaborative and interactive documentary about the 18 day uprising in Egypt. 18DaysInEgypt is an attempt to “showcase the power of crowd sourced documentary filmmaking.”

The people behind the project

The team behind the project consists of software developer Yasmin Elayat, documentary filmmakers, Jigar Mehta and Alaa Dajani, Technology Transfer Office Director at the American University in Cairo, Ahmed Ellaithy and producer, Hugo Soskin, along with the team at Emerge Technology.

Taking advantage of the incredible amount of photos, videos, tweets and stories that emerged out of Egypt from January 25 to February 11, the project aims to bring all of that together in a timeline that will allow you to follow the story minute by minute.

This is not the first attempt to tell the story of the Egyptian uprising through the tweets of those involved. Tweets from Tahrir, a book which was published last month, recounts the story chronologically, as it was told on Twitter. The difference is, of course, that editors scoured Twitter for the relevant tweets. 18DaysInEgypt is encouraging the Internet to come to them. And the team plans to take it one step further, giving visitors a complete online media experience.

Where it all began

Yasmin Elayat gave The Next Web some insight into why they are doing this, saying, “The idea began as a crowd-sourced film. My partner Jigar Mehta noticed that a large number of Egyptians were recording every event using some type of recording device whether it was a cellphone or a camera. He had the idea of using all this material generated by the crowd to create a crowd-sourced film to tell the story of those first 18 days, using the media generated by those who were there.”

Elayat adds to that why it matters to her as an Egyptian, saying, “I also have a personal stake in telling this story as it happened, by those who were there. Not filtered through anyone’s lens. History is not a linear, single voice – so why should the story of the Egyptian revolution be?”

Tailoring crowd sourcing to an Egyptian audience

They have also kept in mind the low Internet penetration rates in Egypt, and are putting together a team that can reach beyond the upload system they have built. Elayat explains, “We are also recruiting volunteers and interested individuals to help us collect media and stories from all around Egypt, on the ground, this summer. We want our platform and the film to tell the untold, underreported stories of the first 18 days of the Egyptian revolution, and not only focus on Tahrir.”

The world was very clearly focused on one small microcosm in the uprising – the now infamous Tahrir Square. With this method, 18DaysInEgypt could easily be highlighting some of the most pivotal moments that took place in other cities in Egypt, such as Suez and Alexandria, moments that none of have heard about or seen.

The project is another example both of the power of social media and of crowd sourcing. Regardless of what pushed the Egyptian uprising forward, it can’t be denied that Twitter, Flickr and YouTube played a large part in telling the story. But the 18DaysInEgypt team doesn’t plan on stopping there.

What comes next?

Realising they were on to something, the platform they have built will be extended to other events and stories. “As we started developing the idea and building the tools to help us collect material from the community, we realized very early on that the platform we are building was a very powerful tool. We are building a collaborative-storytelling platform that would enable any crowd or community to tell the story of any event or uprising as they saw it, raw from the source, from the ground.”

There’s no limit to how the platform can be used, with Alayat citing anything from football matches to the upcoming parliamentary elections as examples, and as such, they intend on opening it up to other projects in the future.

The power of crowd sourcing cannot be denied, and as Alayat points out, “Most media these days is generated by the crowd. Even journalists and reporters during those 18 days relied on the crowd for their news.”

And Alayat, along with her team, are in a rush to gather the material that emerged in those 18 days. “We believe this digital archive that’s scattered across the internet and on millions of hard drives, cameras and phones across Egypt has a shelf-life, and we have to act soon or these important stories will disappear.”

Alayat points out a recurring image that can probably be seen in just about any footage during the uprising in Egypt: “People’s outstretched arms in the air with a cellphone in their hand recording or taking pictures of the events. A majority of Egyptians were documenting everything already so well and they continue to document news and events on the ground as the country transitions and builds.” With that in mind, crowd sourcing made the most sense as a means of collecting data for this project.

The submitted raw material will be available on the website, while the team simultaneously puts together a feature length documentary, which will be available by the anniversary date of the uprising, January 25, 2012.

18DaysInEgypt is still recruiting volunteers for their grassroots project, and details on how to apply are available on the website.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.