This is the third in our Future Of series, where we analyze and dissect one facet of life that’s been impacted by digital technology. Today, we look at cinemas.

“I say to you that the VCR is to the American film producer and the American public as the Boston strangler is to the woman home alone.”

A controversial claim for sure, but this utterance from Jack Valenti, former President of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) helps highlight the fears that emerging technologies can cause amongst those with an interest in the status quo. In this instance, the underlying concern was that VHS-enabled time-shifting meant that viewers could not only copy and distribute copyrighted broadcasts, but also fast-forward commercials, which could discourage advertisers.

During the so-called Betamax case, which saw Sony challenged by Universal City Studios in 1983-84, the US Supreme Court ruled that copying from TV onto video cassette constituted fair use, and thus was permitted. Things could’ve been so much different in the entertainment industry today had the ruling gone the opposite way.

The subsequent proliferation of home video players actually gave the movie industry a much-needed shot in the arm, given that a film’s lifespan could be extended far beyond its theater release-window, with fans able to purchase or rent their own copy to watch at will. And yes, record from TV too.

Moreover, movie theater attendances were dwindling in many markets anyway, but either through coincidence or some other indirect knock-on effect, this case seemed to herald a reversal in fortunes for some movie theaters.

In the UK for example, cinema admissions had fallen from around 200 million tickets sold per year in 1970, to 54 million in 1984. Since then, sales have risen gradually to a point where they’ve pretty much plateaued in recent times, with sales typically remaining between 150m and 175m admissions per year. In fact, 2012 saw the second-highest number of tickets sold in the UK since 1971.

So what’s all this chatter we keep hearing about the movie industry dying at the hands of home theaters, Netflix, Redbox, LoveFilm, and Amazon Instant Video? It has been repeated so many times, that we might actually start believing it. Before we look at where the humble movie theater may be 5 or 10 years from now, here’s a quick snapshot of cinema attendances from around the world in recent times.

Cinema attendances: A global perspective

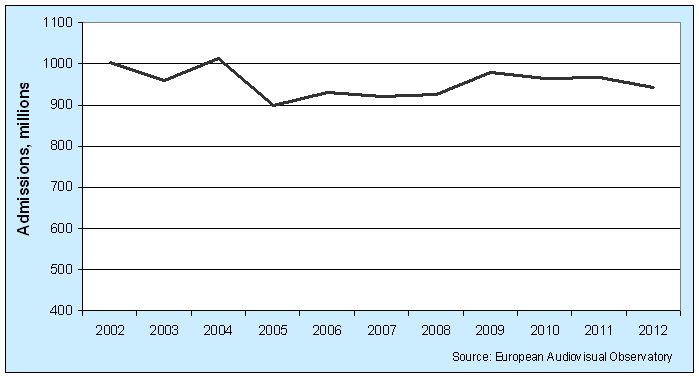

Cinema attendances in Europe fell by 0.9% on average between 2011 and 2012, according to estimates from the European Audiovisual Observatory.

That’s not a massive drop, you’ll no doubt agree, and if we dig deeper into the numbers, some countries actually demonstrated gains – including Finland (+19%), Russia (+5.9%), Turkey (+3.9%) and the UK (0.5%). Bosnia & Herzegovina actually saw the biggest climb overall (+37.9%), while Bulgaria saw the largest drop (-12.9%).

The top four EU cinema-going territories – France, the UK, Germany and Italy, which account for almost two-thirds of all EU movie theater admissions – fell by 2.8% last year. While Northern Europe generally showed big increases in tickets sold, Southern Europe saw the opposite effect, with Cyprus (-5.7%), Spain (-6.5%), Slovenia (-8.3%), Italy (-9.9%) and Portugal (-12.3%) all falling. Among the factors blamed for this drop was the recession and a shortage of locally-produced movies, while a rise in online piracy was noted as a possible contributor.

That, of course, was just one year. What did the past decade look like? A decade that saw DVDs cement their place in livingrooms around the world, not to mention Blu-ray and streaming? Well, the picture hasn’t changed all that much – as you can see here things have fluctuated a little, but it has largely remained around 900m-1bn annual admissions.

Looking at year-to-year ups and downs doesn’t really tell us much. Sure, 2012 might have been slightly down on 2011, but it was actually quite a bit up on admissions in 2005 and 2006.

Reports from other regions around the world were positive too, with China rising by 36%, meaning it edged Japan into second place with its mere 7% increase. And the USA – the largest movie theater market in the world – gained around 6%. It’s worth noting here that revenues and admissions generally matched each other %-by-%, as you’d perhaps expect, and the average cinema ticket price remained about the same.

Indeed, as the Motion Picture Association of America reports, total international box office revenues grew by 6% between 2011 and 2012, with Europe the only region not experiencing growth last year.

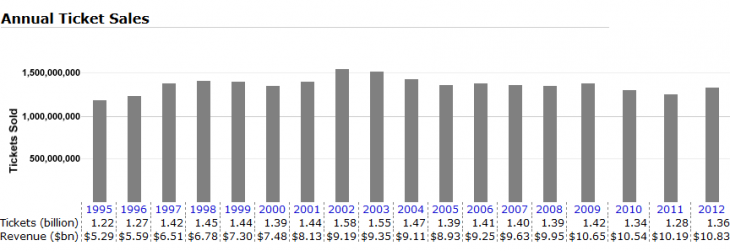

Taking things back a little further, global box office revenue was up 32% compared to five years ago, with the likes of China, Russia and Brazil driving this surge. And as you can see in this graph courtesy of

2011 saw the least number of admissions in the US since 1995. But if you look at the figures between 2000 and 2005, sales varied wildly from 1.39 billion up to 1.58 billion and back down to 1.39 billion. The point is, exponential growth isn’t really possible year-on-year, and a multitude of factors affect the number of people who visit their local movie theater, such as the economy (recessions actually help), movie-selection and even the weather.

There’s nothing to suggest – at the moment at least – that Netflix is eating into the silver screen’s attendances.

What 2013 holds, remains to be seen. Some early reports suggest the recent growth will continue, while others suggest it will drop. In many ways it doesn’t really matter, because year-on-year fluctuations are normal. What we’re more concerned about here is the bigger picture over the longer term, and what the future holds for cinema.

The big threat: Home entertainment

If you can pardon this blatant truism, home entertainment is getting better. Scratch that, it’s becoming phenomenal.

3D TVs, ultra high definition TVs with mesmerising 4K 84-inch screens, wireless surround-sound speaker setups, Blu-ray players and home console systems with Netflix built right-in. Maybe not affordable for every household, but they certainly pose some form of threat to movie theaters.

Sony recently planted tiny adverts on a tennis player during Wimbledon to showcase the clarity of picture in its new line of high-resolution 4K TVs. There are even smartphones capable of shooting video in 4K, while the soccer World Cup in Brazil next year will be produced in 4K, with FIFA currently discussing public viewing venues and cinema screenings. Presumably for the majority of people who evidently won’t have 4K TVs at home by then.

The BBC has already been trialling Super Hi-Vision technology too, which offers 16 times the resolution of standard HD. However, it’s thought this won’t be publicly available until around 2020.

Everything is trying to pull us away from the outside world, and deeper into our sofas. But this has been happening ever since the dawn of television, VHS, DVD and on-demand streaming. Yet cinema attendances haven’t been massively affected in recent years – they fall, sure, but then they rise again.

Adam Leipzig, former Senior Vice President at Walt Disney Studios, former President of National Geographic Films, and current CEO of Entertainment Media Partners, has been a producer, distributor or supervising executive on more than 25 films, including March of the Penguins, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, and Dead Poets Society, garnering somewhere around $2 billion in revenue along the way.

Earlier this week, we spoke with Leipzig about his thoughts on how technology is disrupting entertainment, including the impact home entertainment is having on the silver screen.

“The quality of the in-home experience has really increased – both in terms of picture quality, sound quality and also the quality of content,” says Leipzig. “It’s completely competitive with what we might see in a cinema. In fact, I’d argue that the best writing and the best character development is generally happening on Web series, or televisions series. I would include shows created by Netflix, or by cable networks – there’s better character work and better writing, than we see in most studio movies.”

By way of example, Netflix has moved beyond a simple video-on-demand (VoD) and into the original content realm, launching its first original series — Lillyhammer — in February 2012, followed by House of Cards and Hemlock Grove. And they have mostly achieved wide acclaim for the quality of these shows. As a side point, they also serve as massive incentives for would-be subscribers to opt for Netflix over a rival. HBO too has drawn plaudits in recent times for the quality of its output.

So the home entertainment ‘draw’ is clearly there and growing. But why aren’t movie theaters serving up similar engrossing content?

“Because studio movies are big economic plays – most summer studio movies cost $200m to make, and another $200m to market,” says Leipzig. “The day that they open, the studio is risking $400m on that opening weekend. There is a propensity to play it somewhat safe.”

While it is, of course, a generalization to say that there are no quality movies hitting the big screen, the big blockbusters – the crowd-pleasers that people typically go to the cinema for – maybe aren’t what they once were. It would certainly explain the plethora of sequels and remakes we see these days – it’s all about playing it safe.

“The golden thread for most studios is the franchise, because with a franchise, you don’t have to spend many millions of dollars in marketing to tell people what the story is about,” continues Leipzig. “The story has pre-awareness, and that makes it easier for audiences to decide that they want to go and see the movie. At the same time, it also make movies repetitive and less innovative, and I actually have begun to sense audiences growing tired with franchises and reboots because they all feel so similar.”

So is there a direct correlation between the rise in quality of home entertainment systems – and content – and the fall in people’s desire to visit the cinema? Will having Netflix or Amazon Instant Video plugged into a super-duper, high-def, 3D wonder box really replace the cinema experience? Perhaps only time will tell for sure, but there’s one key factor that’s worth bearing in mind when considering this question.

Social creatures

Leipzig reckons that technology won’t destroy movie theaters, but they will change them.

Why?

“Because I believe audiences now decide – even before a movie opens – whether they will see it in a cinema, or at home,” explains Leipzig. “There are certain types of films that people really love to see at home, and they’re experiencing a renaissance – documentaries are a perfect example. Documentaries have a very limited theatrical cinema life, but they are exploding on online services such as Netflix and Hulu.”

Conversely though, Leipzig says that some movies work much better in a large social setting.

“Comedies are a great example – comedies are not so funny if you’re sitting alone at home. But they’re really funny in a theater with 400 other people,” he says.

“I think there will always be a demand for getting out of your house and experiencing things with other people, in a communal setting – we’re communal creatures, we’re social creatures, we love to get out and experience things with our fellow citizens.”

So, certain types of content may flourish in a home environment, while others will continue to thrive in an ‘out of house’ experience, as the human social gene works behind the scenes. And it’s worth dwelling on this point.

There is often an assumption that technology is somehow transforming everyone into antisocial hermits, but I really don’t think that’s the case. Sure, folk may spend time at home scanning their Facebook stream, but that isn’t replacing their social life. Is it really any different to what’s been happening for decades – watching Dallas or Big Brother at home alone? Not everyone is staying at home because they’re ‘on Facebook’ or watching TV, but they need time away from the outside world.

In the end, everyone has an insatiable urge to meet up with other humans – friends, parents, sisters, brothers, work colleagues – and do things together. And on any given afternoon or evening, they can go drinking, clubbing, jogging, bowling or, indeed, to the cinema.

Movie theaters have served as social destinations for a century. Sure, you’re not actively socializing when you’re watching the movie, but it’s a communal experience that you talk about before, sometimes ‘during’ – you know who you are! – and after. All the Netflixes, 3D TVs and Blu-ray players in the world won’t change that desire, but as Leipzig observed, it may change the finer nuances of the experience.

Connected cinemas…no…noooo….NOOOOO!

There are still a few sanctuaries from the blips, clicks and beeps of mobile phones, such as airplanes and undergrounds. But that is changing.

Airlines are increasingly latching on to the desire to stay connected by offering in-flight WiFi, while 50 meters of thick concrete no longer stops underground travelers from watching cat skits on YouTube. It’s only a matter of time before WiFi blackspots are the stuff of folklore.

But what about cinemas? Unlike trains and planes, there has never really been any barriers stopping movie theaters from offering their patrons WiFi, there’s just a generally-accepted principle that mobile phones and movies are about as compatible as an ashtray on a motorcycle.

Could this change though? Could this whole second-screen craze transcend the living room, hop on a number 24 bus and make its way to your local multiplex?

Ex-Googler Hunter Walk recently kicked up a storm when he suggested some cinemas should offer tech-addicts such as him WiFi, low-lighting and a general forum for kicking back as though it’s their home. It was purely a speculative post that asked the question, but it garnered a lot of feedback, mostly negative. In his post, Walk says:

“In my 20s I went to a lot of movies. Now, not so much. Over the past two years becoming a parent has been the main cause but really my lack of interest in the theater experience started way before that. Some people dislike going to the movies because of price or crowds, but for me it was more of a lifestyle decision. Increasingly I wanted my media experiences plugged in and with the ability to multitask. Look up the cast list online, tweet out a comment, talk to others while watching or just work on something else while Superman played in the background. Of course these activities are discouraged and/or impossible in a movie theater.

“But why? Instead of driving people like me away from the theater, why not just segregate us into environments which meet our needs. I’d love to watch Pacific Rim in a theater with a bit more light, wifi, electricity outlets and a second screen experience. Don’t tell me I’d miss major plot points while scrolling on my ipad – it’s a movie about robots vs monsters. I can follow along just fine.”

At the time of writing, somewhere in the region of 500 comments have been left on his blog post, and the general sentiment can perhaps be best summed up by the commenter going by the name of tjp77:

“Because WHY would I go outside my house and pay for the exact same experience I can have inside my house? What value is being added?

“That’s the whole point of going to the movies; to provide a substantially different experience than what you’d have in your own living room. You, on the other hand, want to make the movie theaters even more like your living room for some reason.

“This is a bad idea, sorry. The number of people who might enjoy this experience is infinitesimal. Certainly nowhere near enough to actually support a profitable business.”

Actor Elijah Wood even got involved:

@hunterwalk You can have that experience. In the comfort of your home. A ludicrous idea to create a passive viewing experience at a theater.

— Elijah Wood (@woodelijah) August 8, 2013

Walk posted a follow-up piece explaining his thinking in more depth, but it was interesting to see the vehemency of the reaction to his proposal. That’s all it was – a guy thinking out loud on his own blog – which suddenly got a lot of people hot and bothered, lambasting him for merely stating that he would sometimes like to cut-loose and do other things while watching a movie in the theater.

But that is the strength of feeling on the matter. While it seems that some cinemas have flirted with WiFi before, it’s not something people are going to accept without a fight.

That said, WiFi isn’t really needed these days. Many cinemas receive perfectly good 3G or 4G signals, which means anyone’s free to tippy-tap on Facebook while watching Batman. The good news, however, is that it’s still largely taboo – if you do start playing Angry Birds during a movie, there’s a good chance someone will give you a piece of their mind. Or maybe even throw a bird at you, in an ironic act of aggression.

Embrace…or not embrace

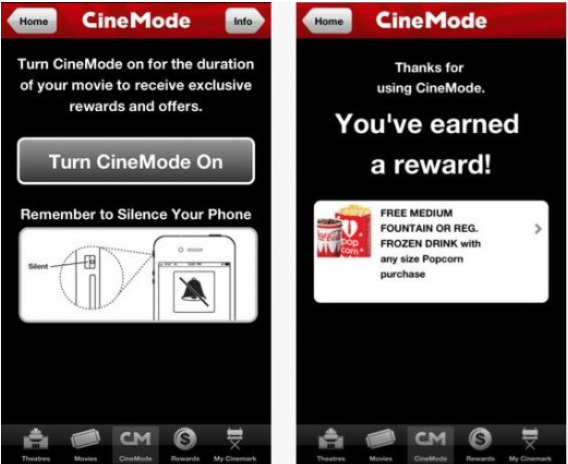

US theater chain Cinemark actually rewards patrons for not using their mobile phones during movies. When the movie’s about to start, you launch its app and click ‘Turn CineMode On’. Your screen will then dim, and you’ll be prompted to set volume to vibrate.

Assuming you stay in CineMode for the duration of the movie, you will earn a reward each time you see a movie, for example a free drink when you buy some popcorn. From what we can tell, there’s nothing stopping anyone from activating this feature from home and gaining rewards anyway, but this is probably more of a souped up incentive to get people to buy some over-priced popcorn than anything else.

On the other side of the fence, cinema advertising company Screenvision launched a second-screen experience for movie theaters last year. Called The Limelight, it lets users browse additional content before the movie begins. To access this pre-movie content, users must download an app called Screenfanz.

The app includes a range of entertainment options, from information on movies to gaming and social features. For instance, movie-goers can check-in, share content through Facebook, earn points and compete for film tickets.

And earlier this year, Screenvision teamed up with Shazam, which saw Shazam’s TV advertising platform arrive in movie theaters across the US. Similar to The Limelight, it encourages moviegoers to use their smartphones during the ads, letting them access special offers, enter sweepstakes and more.

It may not be standard protocol yet, but moves are being made to normalize mobile phones in theaters, though the efforts are confined to pre-movie. But it surely can’t be too long before we begin seeing this kind of initiative creep into the actual movie too. Right? In many ways, it seems inevitable, but I do hope I’m wrong.

Cinemas of the future

Just as digital cameras have have all but consigned traditional film to the history books – ask Kodak – cinemas too are shifting away from 35mm to digital. This is much to the chagrin of many film-makers though, including Quentin Tarantino, who has suggested he may retire from directing movies if his work won’t be projected to screens from reels.

Just this month, a small Rhode Island theater secured more than 100% of its $55,000 funding target on Kickstarter, as it looks to avoid closure by converting to digital projection. You see, while multiplexes and big-name cinema chains actually share the costs of converting with film distributors, independent theaters typically don’t have that luxury.

According to the latest MPAA figures, more than two-thirds of the world’s 130,000 cinema screens are now digital. There has been a concerted effort to make digital the norm in theaters, with major movie studios looking to phase out 35mm film by the end of 2013. So as with your home TV, the future of cinemas are very much digital too.

Laser projection

In an interview with TechRadar earlier this year, IMAX CTO Brian Bonnick outlined why he feels laser projection will play a big part in the future of movie theaters. Indeed, IMAX is currently testing this new technology, with trials expected this year, beta tests in 2014, and potential widespread launch by 2015.

It seems that laser projection’s major plus-point is its contrast ratio – in other words, the brightness of the whites and the darkness of the blacks, with Bonnick noting that this is “one of the most important things” to a viewer’s experience. He says:

“In digital a current 4K projector has contract of between 1500:1 to 1700:1, a 2K projector is up at around 2100:1, and our existing digital IMAX is at 2600-2800:1 – it’s 30 per cent higher but not where we need to go.

It’s a big problem with digital projectors. IMAX film projectors offer up between 3500:1 and up to 5000:1 on a good day and if the print was done well, so that’s the benchmark. With IMAX Digital Laser, we are looking at contrast ratios of 8000:1 and higher.”

It’s food for thought, and will be interesting to see how this one pans out.

3D

It would be somewhat remiss of us not to mention 3D. Since the 1950s, the movie industry has gone through a number of 3D resurgences, but it never quite managed to become ‘mainstream’. That has changed in recent years though.

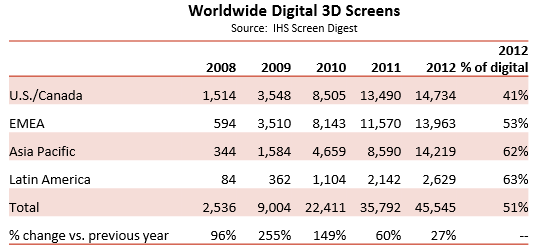

MPAA figures state that US 3D box office figures in 2012 were about similar to that of 2011 ($1.8 billion), even though there were fewer 3D film releases. The number of 3D-capable screens have been steadily rising too, though the explosive growth of 3D screens hasn’t continued from where it started in 2009.

In 2012, almost half (48%) of all US and Canadian moviegoers viewed at least one movie in 3D, according to MPAA figures.

The jury may still be out on 3D, but it’s far from a fad. The 3D experience can be exceptional with the right movie – Avatar, for example, was pretty mesmerizing (visually, at least). And nature documentaries are also particularly enticing. But one can’t help but feel if 3D was going to take off, it would’ve done by now – it likely has a future, but it isn’t the future.

“I think 3D is here to stay, but it is not the new economic driver of the movie business.” Adam Leipzig.

4D

And what about 4D? Spy Kids 4 hit theaters back in 2011, attempting to bring smells into the cinematic equation via scratch-and-sniff cards. It wasn’t the first movie to attempt this – just look at Smell-O-Vision back in the ’60s – but it’s safe to say audiences haven’t really taken to this type of 4D.

However, that fourth dimension doesn’t need to be ‘smell’, does it? Vibrating seats seem like a much better idea, with movements in your chair corresponding with actions on the screen. Some cinemas already have this, with the UK receiving its first such auditorium just last year, kicking off in the country’s busiest cinema in Glasgow. A handful more cinemas across the UK followed.

There are thousands of D-Box seats in cinemas across North America, Asia-Pacific and Europe. While they haven’t really taken off in a big way yet, they do at least hint at the direction cinema may be heading. We’re talking interactivity, taking the out-of-home experience to the next level.

Check this video of the vibrating seats in action, during an airing of Prince of Persia:

Hyper-Matrix

Created for the Hyundai Motor Group Exhibition Pavilion in Korea, the site of the 2012 Yeosu EXPO, the Hyper-Matrix was a kinetic landscape installation consisting of giant cubes that move in and out of the building’s facade. The resulting effect is pretty mesmerizing, with patterns emerging across the three-sided display. At first, it’s just three flat, blank walls, but it soon comes to life as thousands of individual cubes pulsate and move. Check it out:

It was more just a conceptual art installation than anything else, and there was no moving images projected upon it, but that surely wouldn’t require a massive leap of technological innovation? Imagine that – a screen that actually moves in concert with the visual projections would be something else.

Conceptual urban rooftop cinemas

For many, the romance was removed from the cinematic experience when out-of-town multiplex metropolises became the norm.

For many, the romance was removed from the cinematic experience when out-of-town multiplex metropolises became the norm.

This certainly applies in areas of Tokyo where, as part of the ArchTriumph International Architecture Competition, two people designed a futuristic urban cinema concept.

The problem? Large cinema complexes have drawn audiences away from local cinemas, thus forcing many small theaters that were historically and contextually important to an area, to close down.

Kabukicho, once a key center of entertainment in Tokyo, is the proposed location for the ‘Cinepalego’, which uses the vacant rooftop spaces in Kabukicho to create a network of mini-theaters that spontaneously pop-up.

“Designed by Chansoo Byeon + Daichi Yamashita, the act of cinema going will be completely redefined, becoming seamlessly integrated into day-to-day life. Occupying the vacant space on the rooftop, the cinemas will also be closely integrated with the businesses underneath.”

Though this is just a concept, it does allude to one of the fundamental problems of cinemas today. Generic, bland, uninspiring – all words that could be used to describe many of the suburban sites that house the 15-screen behemoths.

Immersive experiences

Back in August, BBC Worldwide announced what it called “…the first facility of its kind in the world” in cahoots with SEGA. Orbi blends SEGA’s technology with BBC Earth’s content to bring visitors “a supercharged nature experience”.

The Yokohama, Japan-based installation isn’t really a cinema as you’d imagine it today, and it doesn’t sell itself as one. It’s an immersive attraction that takes the public on a multi-sensory trip, putting visitors in the middle of nature and inviting them to use all their senses, including sight, smell, touch and sound.

There are twelve different nature zones, letting visitors become polar explorers and even experience life in the midst of millions of wildebeest as the animals rush past.

With 3D, 4D, vibrating seats, moving walls, rooftop screens, and multi-sensory journeys, this all seems very ‘out there’ and perhaps not the most likely immediate outcome for the theatrical experience 10 years from now. Though it would be nice to see elements of these creep in along the way.

Just as watching Back to the Future 2 is becoming increasingly amusing as we edge closer to 2015, the future of cinemas won’t be any of the above. Multiplexes will probably still be the norm, though it would be nice to see little local gems such as the Ritzy in London’s Brixton remain on the scene.

To look at what the future holds for cinemas, we just have to look at the now.

Democratization: Streaming and on-demand

As things stand, you pay your money to watch one of several pre-set movies advertised at a cinema complex. You have choice, sure, but you can’t choose your choices, if that makes sense.

With cinemas becoming increasingly digital, there will shortly be no need for a time-delay between completing a movie, and shipping it around the country. As things stand, yes, digital files are still sent to theaters on drives or disks, but with improving file-transfer and broadcasting technology, movies could be beamed directly from source, just like Netflix or Amazon Instant. So the only real restrictions then, are those of tradition.

Democratization will likely play a big part in the future of movie theaters. Why have three screens completely sold out, and five sitting empty? With bookings enabled through the Web, mobile phones and hopefully even smartwatches, there doesn’t need to be a limited number of tickets for one screening.

Just as cloud computing gives companies access to as little or as much server power as they need at any particular moment, in the cinemas of the future, space is allocated depending on the demand for a certain flick. Any ‘overspill’ just gets pushed to another screen, and for less in-demand movies, they simply get pushed down to the smaller auditoriums. Supply and demand.

Moreover, movie studios, distributors and cinemas could arrange a Netflix-style library of films to choose from – it could be the entire back-catalogue going back 100 years, every movie from the past 12 months, or somewhere in the middle. Let the public decide.

I paid to watch a special 25-year anniversary screening of Back to the Future in my local cinema back in 2010, and absolutely loved it. I’ve seen the movie a million times on TV since I first saw it back in 1985 on the silver screen, but seeing it again then was special. It would be great to be able to access older films in movie theaters, with customers perhaps ‘voting’ on what film will be shown on the dedicated ‘oldies’ screen every Friday.

Cinemas are currently restricted in what they can offer – it’s been like that since the dawn of the movie industry. But with evolving technology, there is so much room for innovation. All it will take is one enterprising cinema operator to trial a few different things, find a winning formula, and the rest of the pack will follow.

Earlier this summer, Ben Wheatley’s A Field in England, became the first UK film to be launched in cinemas, DVD, TV and VoD all on the same day. This could become the norm in the future – giving people the choice of medium from the start, rather than making them wait several months after the theatrical release to enjoy it, though such an idea would have to be deployed correctly to ensure cinema takings don’t suffer.

An elite experience?

Movie tickets hit an all-time high of $7.96 in the US in 2012, and in the UK – where I live – it hit an all-time high of £6.37 ($10.21). These are just averages though – in some London cinemas that price is easily more than double that. When you throw into the mix popcorn and all the rest, it can be a very expensive evening out. But that’s exactly what it is – an evening out.

There is something deeply enjoyable about sitting in a darkened auditorium with a bunch of strangers all laughing or crying at the same thing. As weird as that may sound.

When people argue, “why pay $10 for a film that’s crap, when you can OWN it in HD three months later”, they’re missing the whole point of cinema.

You’re paying for the experience, though granted this experience is getting particularly expensive in bigger cities. But if someone can’t afford, doesn’t want or simply doesn’t see the point of cinemas, then yeah – they have the option of waiting a few months to watch it on DVD, Blu-ray or Netflix. For the rest of us who love the cinema experience, here’s hoping we’ll start seeing a swell of innovations and technological advances over the next few years and into the future.

Image Credits: Feature Image – Thinkstock | Image 1 Thinkstock | Image 2 Thinkstock | Image 3 AFP/Getty Images | Image 4 Wikimedia Commons | Image 5 Thinkstock |

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.