A couple of decades ago – well before a $10 monthly fee would unlock access to virtually every song ever recorded through streaming services – digital music piracy was rampant around the world. Whether it was because you were young and couldn’t afford to buy MP3s, or simply couldn’t access them in your country, it was all too common to download music shared by other people on the web.

What was particularly interesting back then was the wide range of ingenious methods people used to share tunes. Back in the day, people went beyond simply hosting music on public-facing websites, and instead, found ways to send and receive tracks directly with other internet users. Let’s take a walk down memory lane and take a look at some of the ways people grew their music collections in the late 90s and early 2000s.

But first, a little bit about MP3s

In the 90s, digital music was most commonly available in the form of albums on CDs, which stored about 700MB worth of uncompressed audio tracks – good for a full-length album. But with internet bandwidth and speeds being what they were back then, it didn’t make sense to copy those music files and send them to friends over the internet. A single four-minute song would weigh in at about 42MB in WAV format, and would take roughly three and a half hours to download.

Lucky for music fiends, the MP3 compression format came along in 1993 and made things a lot easier. It allowed for reasonable audio fidelity with comparatively small file sizes, making it easier to rip music from CDs, store them on hard drives (remember, this was back when the average household didn’t have a more than a couple hundred GBs of storage space at best), and distribute them online. That four-minute song I told you about? You could shrink it down to 3.84MB, at an acceptable bit rate of 128kbps.

And with that, we were off to the races.

The rise of Napster – and the fall of the music industry

While a small number of web users had already begun sharing music online through channels like the Internet Underground Music Archive, digital piracy really took off with the launch of Napster, a free file-sharing network that connected people around the world directly to one another.

It was developed by 18-year-old Shawn Fanning while he was a student at Northeastern University, achieved in a 60-hour coding marathon that he put himself through. In 2000, Napster was believed to have experienced the fastest growth of any digital service in history, having amassed some 80 million users at its peak, during its short life span of about two years.

The app was shut down in 2001 after many a legal battle with artists, companies, and music industry bodies in the US – including Metallica, Dr. Dre, and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) – for its role in countless copyright violations.

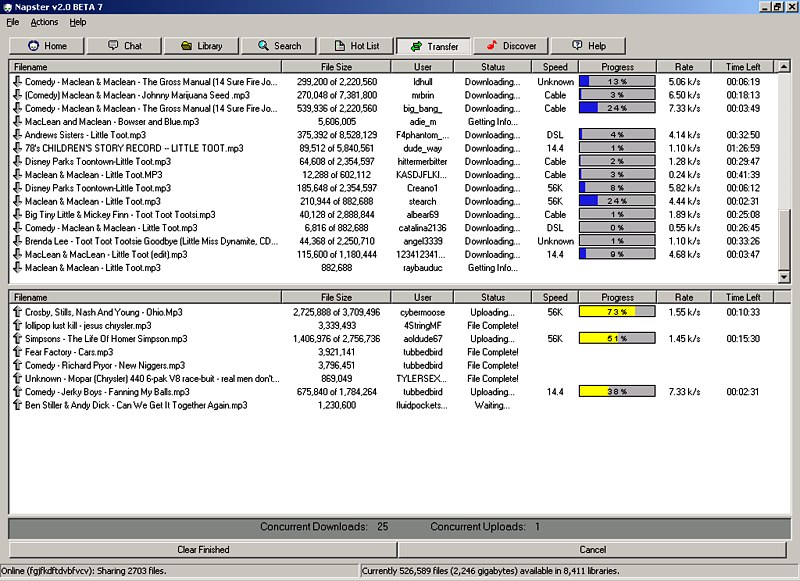

But while it was around, you could simply fire up Napster, search for a song, album, or artist, and see a list of files hosted by people who were online at that time and had what you were looking for. When you clicked ‘download,’ you’d essentially initiate a direct peer-to-peer (P2P) file transfer between your computers, and have those tracks on your hard drive in minutes. It was genius. Undeniably illegal genius, but genius nonetheless.

Napster knocked the music industry on its ass from the time it launched, taking revenues down big time. Though music industry revenues are still below the heights they reached in 1999, they’ve seen an uptick in recent years, with an increase in industry revenues of 16.5 percent in 2017.

I remember checking out Napster briefly, but it closed down before I got much use out of it. But as you’d expect, there were several alternatives back then.

P2P madness

Alongside the monumental growth of Napster, the year 2000 saw the rise of many rival P2P networks, and even more desktop clients for each of them – despite the dangers of building such services being painfully obvious, thanks to the US music industry cracking down on them with all the legal firepower they could muster.

Arguably the most notable of these was Gnutella, which is said to have been the first large-scale decentralized P2P network on the internet, and to have cornered some 40 percent of the file-sharing market at its peak. It was developed that year by Justin Frankel and Tom Pepper, who you might remember as the people behind the popular Winamp music player.

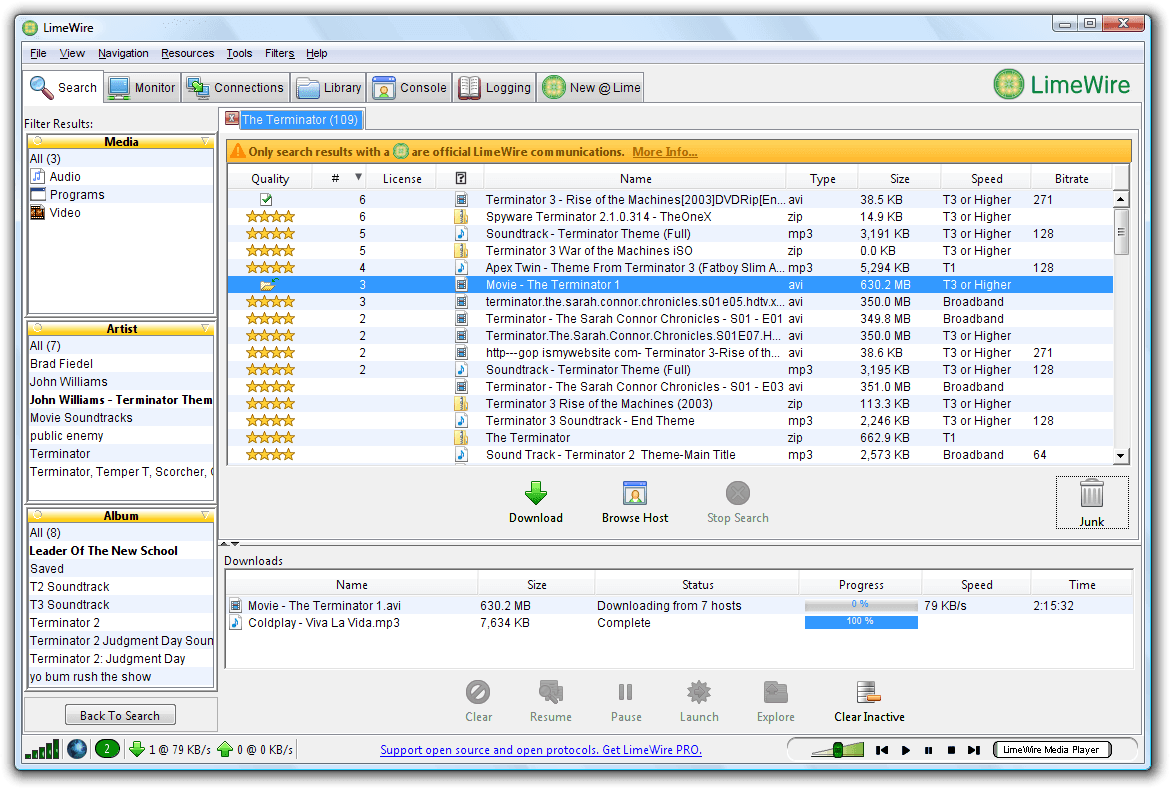

The Gnutella network powered several client apps like LimeWire, Morpheus, BearShare, and Shareaza. Of these, LimeWire was perhaps the best known of the lot, and was estimated to have been installed on every third PC in the world at one point in its existence. In addition to facilitating file transfers, it also included an XMPP-based instant messaging service, so you could chat with people you were sharing content with.

LimeWire was sued by several record labels in 2006, and eventually shut down in October 2010. Most other P2P apps met a similar fate during the 00s, as the RIAA and other bodies and companies from the music industry went legal on them as quickly as they could.

There were other apps that used their own networks, including Soulseek, Ares Galaxy (which spun off from Gnutella and launched in 2002), and WinMX, which offered compelling features like chat rooms and the ability to download files in small pieces from multiple users simultaneously. Here’s the latter in action:

While those were simply shut down over copyright infringement concerns, KaZaa went through a completely different sort of trial. The service, which was developed in Estonia, was sued to hell as well – to the tune of $100 million, in fact – and eventually turned into a legal music subscription service. That’s similar to what’s going on with Napster, which is now owned by Rhapsody and is the brand used by the company for its streaming music service.

Truly old-school: IRC

While you could certainly hop on P2P networks like the ones we’ve mentioned, the OGs opted for IRC instead. It’s a basic chat protocol that was first invented in the late 80s and is still around today. For the most part, it’s designed for text chat, and using IRC involves finding relevant servers that host chat rooms of interest to you.

So if you wanted to download music, you’d first need to find a server that had people sharing tunes in public genre-based chat rooms, and pop into one of them. You’d then have to ask around to see if people in the room had the kind of music you wanted, and initiate a file transfer.

Of course, some folks got clever about it, and set up scripts to crawl their hard drives for songs, and catalog them into text files. Next, they’d employ a script to periodically post ‘advertisements’ promoting the kind of music they had to offer in the chat room, with eye-catching ASCII art banners and lists of artists or albums that you could grab from them.

Once you spotted something you liked in a user’s music catalog, you’d have to request those specific files by entering them along with an IRC command, and that’s it – as long as that user was online, you could download files from their hard drive to yours.

What struck me was that these people sharing music had nothing to gain except goodwill, and perhaps some notoriety in an anonymous chat room. There’s a lot less of this now, but researching this method for this story brought back fond memories of chatting with strangers to learn what was worth listening to – and spending valuable bandwidth to download.

An oldie but a goodie: Audiogalaxy

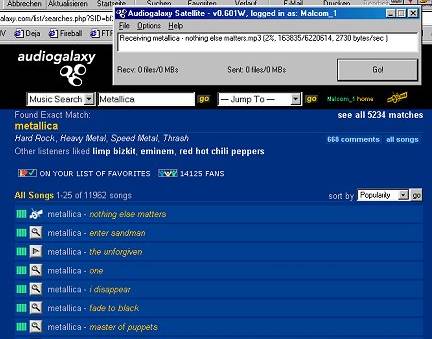

Launched in 1998 (and therefore predating Napster), Audiogalaxy was one of the oldest services for sharing music. It evolved from an index of FTP sites that hosted music into an excellent sharing service with a quirky workflow.

You’d have to first visit the site, search for music that you wanted, and then add files to your Satellite – a piece of desktop software whose sole task was to facilitate anonymous file transfers. Once you’d added the files you wanted to download, Satellite would automatically grab them for you when they were available from other users, all without exchanging any user details publicly.

I was probably around 12 or 13 at the time, and I was just getting into modern rock and nu-metal. It wasn’t always easy to find that sort of stuff in India as it hit the airwaves, so Audiogalaxy was one of the only ways to get my hands on records by Creed, Linkin Park, and Limp Bizkit.

Those were the days – or were they?

While many people found various ways to justify their pirating in the early 2000s, it’s obvious that it didn’t serve the artists behind our favorite records. At the same time, we were discovering new music like never before. Our own Nino de Vries summed up the experience well:

Growing up, I was way into hardcore punk, so much so that I got a Minor Threat tattoo when I was 18. Around I found Soulseek to be the perfect tool to steal music from hard-working musicians who barely made enough money to pay their rent. I had a couple of favorite users who had gigabytes and gigabytes of the best hardcore and I would just leech their entire hard drive in my quest for new music. After that, I found a good local message board where people swapped download links via DMs.

I can’t say that I’m proud of any of this. Sure, I was a young kid with nothing but debt to my name — but stealing music I loved was inexcusable. I’m extremely grateful for modern streaming services; Spotify has every song I could ever want and I happily pay the ten bucks per month for their platform. It’s way easier than having to leave your computer on overnight for Soulseek to complete it’s slow-as-fuck downloads back in the day.

Our Plugged reporter Callum Booth explained how that era turned him into a music aficionado:

I once worked out that I’ve spent close to £15,000 (about $16,600) on recordings of music in my life – and loads more on instruments or gigs. From when I got my first job at 13, up to this very day, I’ve been splurging on CDs and vinyl.

But it was downloading (and sharing) music that really kickstarted my love affair with the format. The first track I downloaded? Basment Jaxx’s ‘Where’s Your Head At.’

I was around 11, and I remember in such vivid detail lying on the wooden floor with KaZaa open on an old laptop screen, waiting for the file to download. It took hours over the dial-up connection. And this is what it was like for a couple of years: an achingly slow progress to grab a couple of songs. It was magical.

Things really changed for me a few years later. I’d moved houses and internet connections had improved massively. One of my friends had a sick computer, loud speakers, broadband, and an office in the loft so we weren’t disturbed. And you know what was on that computer? Motherfucking LimeWire.

At this point in my life (I guess I was around 15), I still bought music magazines. In this age of instant musical gratification, it’s strange to think that I’d read about bands and have to imagine what they sounded like.

So, almost every week we’d crowd round the computer, boot up LimeWire, and download not only the latest singles from bands, but also old classics. And each week I’d leave with a CD filled with that week’s tracks, and blast them endlessly on the stereo in my room. Until the next week. The cycle continued, until my folks got a comparable internet connection. I still have nothing but fondness for those times.

Downloading music exposed me to a world I could’ve never afforded otherwise. I can say with no doubt that I’ve spent more on physical music because I downloaded. It let me experiment with genres. It let refine and discover my taste. And it totally fucking ruled.

My experience was similar: these services opened me up to a world of music I hadn’t come across elsewhere. As a teen in India during this golden era of piracy, it wasn’t easy finding communities and friends who shared my tastes in music. But on P2P networks and IRC chat rooms, there were loads of folks who were only too happy to recommend artists and albums worth checking out – and to beam them across a few kilobytes at a time.

Now that I’m older and wiser, I wouldn’t condone pirating music, especially given how hard it is to make it in the industry in 2018 and earn a living. But I’m certainly a more avid fan of the art than I would’ve been without that experience during my teens, and I’m happy to spend as much as I can afford on records, concerts, and merchandise to support my favorite artists.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.