![[Best of 2019] What World War II can teach us about fighting fake news](https://img-cdn.tnwcdn.com/image?fit=1280%2C720&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn0.tnwcdn.com%2Fwp-content%2Fblogs.dir%2F1%2Ffiles%2F2019%2F04%2F63.png&signature=1e342e5b257cb1c9f0783e0499bf6704)

With local and European elections just mere days away, the UK government is heavily promoting its S.H.A.R.E Checklist campaign across social media, which warns against the dangers of proliferating fake news.

Just because a story is online, doesn’t mean it’s true. The internet is great, but it can be used to spread misleading news and content.

Make sure you know what you’re sharing. Don’t feed the beast. Use the S.H.A.R.E checklist.— Cabinet Office (@cabinetofficeuk) April 15, 2019

“Just because a story is online, doesn’t mean it’s true,” says a tweet from the Cabinet Office’s official account promoting the campaign. “The internet is great, but it can be used to spread misleading news and content.”

The tweet links to an official government page, which sternly warns against the risks posed by fake news to the overall health and harmony of society. It explicitly highlights anti-vax propaganda, which contributed to an outbreak of measles during 2017 and 2018, as well as hoax news stories during the 2011 London riots, which convinced people the situation was more violent and dangerous than it really was.

Imploring readers to not “feed the beast,” the page offers a five-point checklist to identify hoax stories, which includes checking the source of the story, reading beyond the headline, and checking for domain-squatting URLs and manipulated images.

Understanding Rumor

What’s the old saying, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Or, translated roughly, the more things change, the more they stay the same. The UK is using 21st century tools to fight a problem that’s frustrated governments for centuries. Historical British and American governments, especially the wartime ones, were deeply concerned about how the proliferation of fake news and rumors could impact the war effort.

A rumor containing the slightest grain of truth could, for example, provide a tactical advantage to the enemy, giving clues to the location of allied troops, or shine a light on upcoming military advances. Rumors could also harm national morale. If people are led to believe that defeat is imminent and unavoidable, they’d perhaps be less inclined to volunteer in ammunition factories or on farms and would have less of an appetite to “make do and mend.”

The governments of the time were keenly aware of the dangers posed by fake news. Rumors, if left to fester, could inadvertently result in Wehrmacht Panzers parading through the sleepy home counties, or imperial Japanese soldiers landing on the shores of California.

In response, the allied governments adopted a forward-thinking and science-based strategy, as outlined by York University academic Cathy Faye in her 2007 paper Governing the Grapevine: The Study of Rumor During World War II.

Faye predominantly describes the US response to Axis rumors. She explains that, in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor, the American government responded by recruiting heavily from the social science departments of universities.

“Hardly had the smoke cleared from Pearl Harbor before the government began drawing special psychologists into its war-time activities,” wrote academic Dorwin Cartwright in 1948, one of the figures quoted in the paper.

By March 1942, just a few months after the Japanese incursion into Hawaii, Washington D.C. was filled with psychologists and social scientists, many of whom claimed expertise in areas such as “leadership, conformity, public opinion, and morale building.” Uncle Sam promptly tasked these academics with understanding the nature of rumor and propaganda, and how it could be used as a tool of warfare, both by the United States and the Axis powers.

The (Spin) Doctor Will See You Now

The United States was a potentially fertile breeding ground for enemy propaganda. After the catastrophic defeat at Pearl Harbor, it was demoralized, with much of its naval assets destroyed. Furthermore, the country wasn’t especially enthusiastic about getting entangled in another bloody conflict. During the interbellum years, the US had an explicitly isolationist foreign policy, which saw it avoid overseas conflicts and abstaining from the League of Nations.

Recognizing this, the government developed so-called “rumor clinics,” which you could conceivably describe as the Snopes.com of the era. These university-based institutions were staffed by patriotic academics and advanced students, and were responsible for identifying, analyzing, and countering rumors.

This was an important job. All members were required to undergo an intensive two-week psychological warfare course. Once they’d completed “basic training,” they were ordered to record all rumors discovered locally. These would be shared during meetings of the “clinic” and sorted into two piles. The benign ones were to be addressed by the local teams, while the more sinister ones were to be relayed to the academics working in Washington.

These rumor clinics weren’t entirely successful. The intelligence and military establishments of the day were deeply uncomfortable with this critical role being left in the hands of civilians. This pressure led to the project being cancelled by the government, which would later study rumors without the assistance of the clinics.

In many respects though, this was a blessing in disguise. Working under their own guises allowed universities to continue operating rumor clinics with a level of autonomy that they otherwise wouldn’t enjoy under the government.

The Boston Rumor Clinic, for example, operated by Harvard academic Gordon Allport and his student assistant Robert Knapp, was extremely successful in engaging with the public. It published a weekly newspaper column which analyzed and refuted rumors, much like the modern-day fact-checking services FullFact and Snopes.

Prevalent rumors were chosen for analysis and refutation. These rumors would be labeled as such and printed in italics, followed by an answer or refutation labeled “Fact” and printed in bold type. Frequently, the column would include a psychological analysis of prevalent rumors, aimed at increasing public understanding of the psychological motives underlying the spread of different types of rumor. The column was also distributed to high schools and posted on community bulletin boards, with the expectation that such measures would promote public understanding of rumor in wartime.

The response to this was hugely positive, with members of the public regularly sharing rumors for the researchers to debunk. As the Boston Rumor Clinic’s researchers found out, these took many shapes, and ranged from the plausible to the eccentric.

The most common rumors analyzed in the Herald were those pertaining to waste of rationed materials, government dishonesty and corruption, mistreatment of American soldiers, the imminence of defeat or victory, and the future value of war bonds. Unusual or less feasible rumors were also considered, including a story circulating about glass or poison being found in crabmeat packed in Japan and a story about a woman employed at a shell filing factory whose head exploded after receiving a permanent at the local beauty parlor.

The Boston Rumor Clinic would briefly become the benchmark for how the fight against fake news would be waged domestically. It was, however, hamstrung by a fraught relationship with the intelligence institutions of the time. Towards the end of 1942, the OWI (Office of War Information) published a 30-page document dubbed the “Rumor Bible,” which dictated how university rumor clinics were to operate.

Nothing Ever Changes

Much of the advice went against the practices of Allport and Knapp. The Rumor Bible specifically warned against debunking rumors and fake news, as doing so may inadvertently elevate them to a level of prestige they otherwise wouldn’t have and could cause distress to members of the public. “By calling a silly story a ‘rumor’ you automatically lend it dignity,” wrote the OWI.

It’s interesting to see how this conversation is replaying in peacetime. People are still unsure how to address the problem of fake news. In the absence of a tried-and-true methodology, it remains a complicated and menacing social minefield.

After the 2016 US general election, which was marred by a slick and highly-targeted propaganda campaign that took advantage of most major social media platforms, Facebook responded by marking hoax and fake stories as such. At first, Facebook marked deliberately misleading content, and linked to thorough analysis, like that penned by Allport and Knapp in their Boston Herald rumor clinic column.

Surprisingly, Facebook’s strategy backfired. Instead of persuading people the stories were false, the warnings instead made people more convinced in their veracity. Furthermore, they actually made some users more likely to share them.

In 2018, Facebook reversed course and dramatically shrunk the warnings, instead relying on other approaches, including downranking fake stories within the News Feed.

The War Continues

It’s hard to quantitatively analyze the successes of the rumor clinics. Some approaches were more successful than others. The Boston clinic, for example, was extremely good at outreach. At its peak, it received over 1,100 rumors for analysis and classification, essentially pioneering crowdsourcing long before crowdsourcing even entered our collective lexicon.

Things become a lot more transparent when you look at the failures of the era. Researchers working at rumor clinics were hamstrung by jealous — and often deeply political — government institutions who were loath to let civilians take the lead. This manifested itself in programs being arbitrarily suspended, and the emergence of several different rivaling approaches.

One can speculate what would happen if the US government trusted placed its trust in the abilities and patriotism of its experts, and avoided the bickering and petulant infighting described in Cathy Faye’s paper.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter.

The Allies triumphed in World War 2. And it wasn’t propaganda that brought about that victory, but rather the courageous sacrifice of an entire generation of men and women.

Furthermore, one could argue there’s something innate in human nature that causes us to gossip and lie. This makes any effort to combat it utterly futile, a bit like King Canute trying to hold back the tides using the sheer force of his own hubris.

The deeper you dive into history, the more examples you see of governments and religious institutions trying to combat rumors and propaganda, with varying levels of success. The earliest examples are found within the dusty pages of the Bible’s Old Testament, which dates back to the bronze age and is unambiguous in its condemnation of prevaricators.

Leviticus 19:16 says: “Do not go about spreading slander among your people,” while the eighth commandment (or ninth, depending on the Christian tradition you adhere to) is the well-known prohibition against bearing false witness.

Fast forward a few millennia, and you encounter some truly brutal examples of jurisprudence against gossips and liars. During the middle and early modern periods, gossips in England and Scotland were punished with the Scold’s Bridle — a metal mask designed to humiliate the wearer, which contained a sharp iron tongue-compress in order to prevent the penitent from speaking.

This punishment was primarily used against women. However, there are historical records of it being employed against particularly mendacious males.

The tweet is mightier than the mask

With that in mind, I’m glad that the British Government is using social media instead of torture in its fight against fake news.

The finer details of the S.H.A.R.E campaign are somewhat thin on the ground. In order to find out more concrete information, TNW sent the Cabinet Office a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. We’re particularly interested in the cost of the campaign, and how many people it’s reached so far. When we hear back from them, we’ll be sure to update this post.

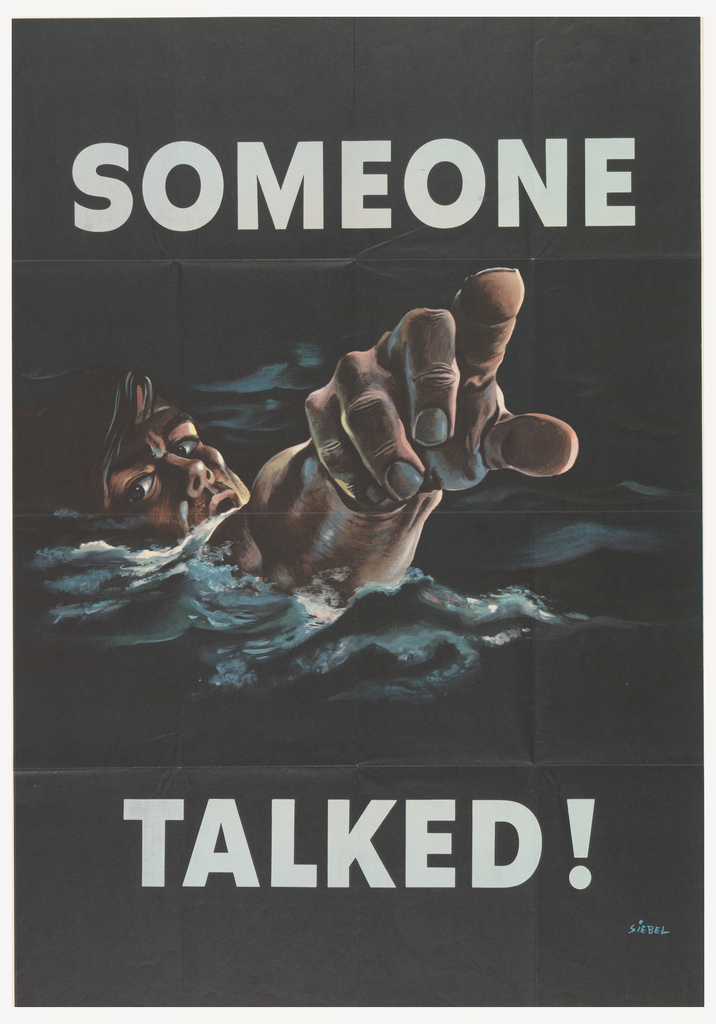

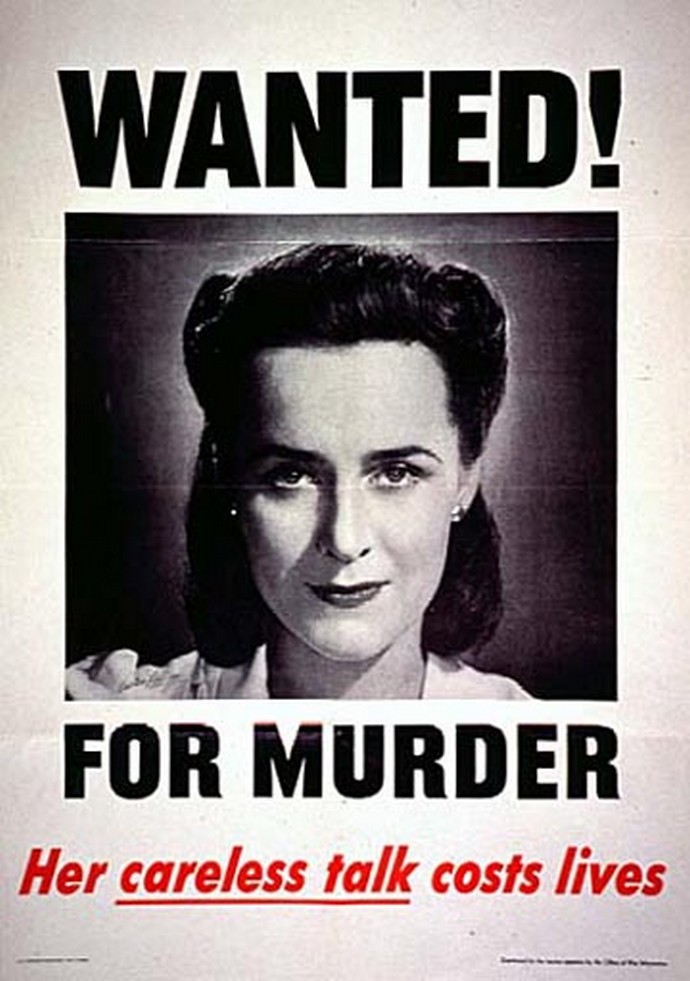

What’s especially interesting about the S.H.A.R.E campaign is that it exists in an era when public confidence in the government is at an all-time low, and almost all conversation is bidirectional. Unlike the iconic propaganda posters of World War 2, the public is able to directly criticize this effort through comments and tweets. And you can bet they are.

— James Cameron (@OblivionMedia) April 29, 2019

“Just go back to work and stop wasting taxpayers time with this nonsense. The government has been lying to the people for the past two years. Don’t lecture us about #fakenews,” wrote one person.

“Apply this to yourselves then we will start listening,” said another.

Another trend found in the comments for the tweet are people using the campaign to criticize other government-linked institutions, namely the BBC, which is often accused of bias by people on all sides of the political spectrum.

“Wow! That’s should be a [sic] official commercial before any BBC show,” said another Twitter user.

I suppose if I was a particularly conspiratorially minded person during World War 2, I’d conceivably regard the warnings from the Rumor Clinics as a shady cover-up. If you don’t have much faith in institutions, be they media or government, it’s easy to imagine them working against your best interests. If you’re adamant the government is lying to you, it’s easy to dismiss everything it says out of hand.

The comments do an excellent job of highlighting the challenges posed by fake news in the 21st century. Not only is there a hyper-polarization of society, largely caused by the existence of unambiguously partisan news sources (of all flavors, I’m not just talking about Fox News), there’s also no shared consensus when it comes to the fundamental facts of life. And how do you overcome a problem like that?

Bring back the Scold’s Bridle, I say.

TNW Conference 2019 is coming! Check out our glorious new location, inspiring line-up of speakers and activities, and how to be a part of this annual tech extravaganza by clicking here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.