In the recent years and in the light of the drawn out Lance Armstrong doping scandal, the Tour de France has been under pressure to crack down on doping tendencies within the race. Lance Armstrong himself argues that everyone within the cycling culture is using body-enhancement drugs, and that in order to remain competitive in that sport, there’s no option other than to participate in doping.

This year’s winner of the yellow jersey, Chris Froome, has also come under scrutiny amid allegations of doping. How prevalent are performance enhancing drugs in the Tour de France?

As is our custom here at DataHero, we dug into some sports data to try to answer this question.

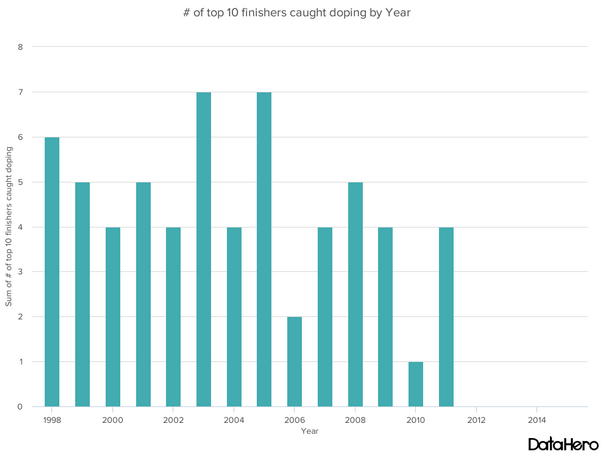

The chart below indicates that Armstrong may have a point about the PED usage in the Tour de France. From 1998 to 2012, about 44 percent of the top 10 finishers of the Tour de France were using PEDs at the time.

However, we also see some really encouraging data within the past 3 years from 2012 to 2015, where none of the top 10 finishers in the Tour de France appear to have been taking PEDs.

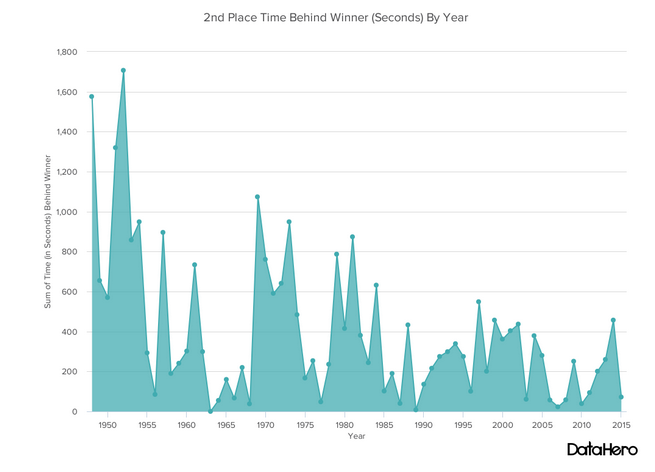

If we take a look at how close races are over time, we see that cycling is (like most sports) becoming more and more competitive. Cyclists coming in second are closer and closer in finishing time to first place winners.

One interesting thing to note is that 2003 and 2008 are some of the closest races, and those are two of the years that see the highest number of top 10 finishers who were caught doping. Again in 2015 we see the second place winner, Nairo Quintana of Colombia, missed first place by a mere one minute and twelve seconds.

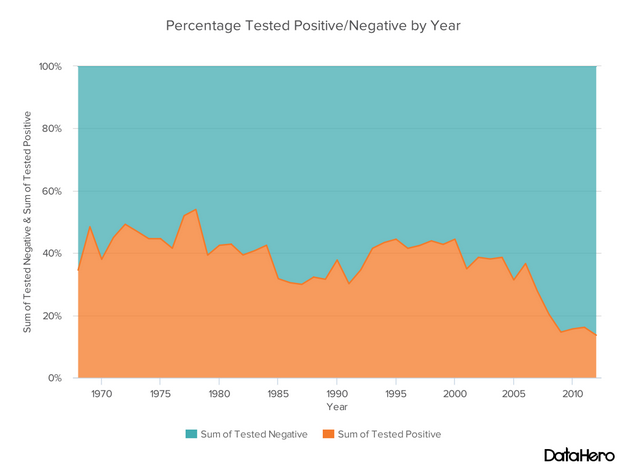

If we take a look further back than 1998 and expand this data to all Tour de France participants, we see a little bit more encouraging picture of doping in the Tour de France.

The reported number of positive tests for PEDs has decreased as a percentage of overall samples collected. An optimist would say many of the anti-doping efforts encouraged by the UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) are a success. For the first time in the Tour de France, nighttime doping tests will be administered to cyclists this year. Biological passports were also introduced in recent years.

These tests factor in not just the urine and blood samples of Tour de France participants, but “try to identify suspect constellations of biological markers that can not be caused or explained by other means than doping” according to Professor Schumaker, of the University of Freiberg who is an expert in evaluating blood profiles for the biological passports.

A pessimist would say that dopers are simply becoming more sophisticated. Doping is essentially an arms race; some chemists work to create performance enhancing drugs that are undetectable, while chemists at anti-doping agencies are racing to detect those same drugs. After all, Lance Armstrong won a successive seven Tour de France races between 1999 and 2005 and didn’t definitively admit to doping until 2012.

EPO, the drug most frequently used by Lance Armstrong, stimulates creation of red blood cells, allowing more oxygen to circulate and thus giving athletes more endurance. The hard part of identifying PEDs is that every new drug requires a new test, giving athletes a window of opportunity. Some drugs have very short half lives, a matter of minutes. This is why the nighttime doping tests may prove useful at the Tour de France this year.

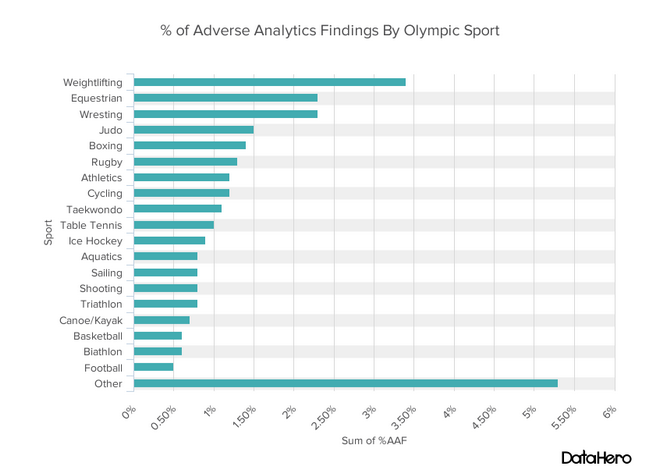

Is doping in the Tour de France really much worse than other professional sports though? Data from the World Anti Doping Agency says no. The following chart is a representation of the percentage of adverse analytical findings (doping chemicals present) broken down by Olympic sport for 2013. This includes both in competition and out of competition stats.

The worst doping offenders appear in strength-centric sports (weightlifting, wrestling, boxing, etc.) Equestrian makes an interesting appearance, and in this sport both equine and human participants are tested for PEDs. Cycling comes in 8th for the highest percentage of AAFs. Incidentally, American football (not an Olympic sport) has an AAF percentage of about 6%, much higher than the other sports represented here.

Does this mean that in order to be competitive in the Tour de France, one must take performance enhancing drugs? Possibly. Is this an issue solely for cycling? Absolutely not. Every sport struggles with performance enhancing drugs, and every athlete wrestles with the dilemma of taking these PEDs to remain competitive, or staying “pure” and potentially losing to others who have chosen to take performance enhancing drugs.

Read Next: Google guides you through the Tour de France

Image credit: Shutterstock

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.