If you’ve been following digital trends over the past few years, you’ll probably be aware of the hockey stick-growth of crowdfunding as a ‘thing’. It’s everywhere.

From smartwaches and ad campaigns, to mobile phones and Google Glass apps, seemingly every industry has taken to the Web’s myriad of crowdfunding portals to garner the necessary funds to help take ideas out of minds and into production.

Launched in 2009, Kickstarter is perhaps the most well-known crowdfunding platform and yesterday it revealed some interesting numbers. In 2013, campaign organizers raised $480 million from 3 million people, which works out at roughly $1.3 million each day. Or $913 every minute. Moreover, 800,000 backers pledged money for at least two projects, while roughly 81,000 supported more than 10. And 19,911 projects reached their funding target.

Compared to 2012, when 2.3 million people pledged a total of $320 million to see 18,109 projects through to funding on Kickstarter, then it’s clear that crowdfunding isn’t going away any time soon. And why should it?

Given the recent surge in projects funded through the likes of Kickstarter and Indiegogo, here we take a look at the past, present and future of crowdfunding.

The past

Not surprisingly, crowdfunding as a concept wasn’t born out of the Internet age – the Web just made things a whole lot easier. The idea that multiple people could club together to see an idea through to fruition is actually, well, not that innovative.

Way back in 1713, poet Alexander Pope took advance subscriptions to translate Homer’s Iliad from Greek into English – it was a seven year project that saw a single volume produced each year.

Also, when France built the Statue of Liberty for the US back in the 19th century, she was shipped across the Atlantic in pieces to be assembled Stateside – however the US struggled to raise the required $250,000 to build a granite plinth to house her. With a number of potential funding conduits exhausted, publisher Joseph Pulitzer launched a fundraising campaign in his newspaper, The New York World, which ultimately raised enough cash from a staggering 160,000 donors to cover the remaining $100,000 needed to erect the statue.

History is littered with similar escapades, but with the advent of the Internet era, things have opened up greatly.

‘Electronic watering holes’

Fast forward to 1997, and British rock band Marillion disappointed its US fan-base when it announced it would have to can a planned tour after its American record label went bankrupt and ultimately dissolved. Marillionites, as the band’s fans are affectionately known, took to the fledgling communication network known as the World Wide Web to spread the word and garner donations from fans everywhere.

A Chicago Tribune report at the time read:

“Marillion’s on-line followers, known as Freaks (they take their name from the lyrics of one of the band’s songs), tout themselves as computer-savvy music fanatics who discuss the group on the Internet’s World Wide Web (www.marillion.com) and Newsgroup message boards (alt.bands.marillion). It was at these electronic watering holes where Jeff Pelletier, an optical engineer in Bedford, Mass., conceived the fundraiser to bring Marillion to the States.

Pelletier credits the ‘instant communication’ of e-mail and on-line forums with the fund’s success. When he proposed his plan to his fellow Freaks, the response was overwhelming.”

Around $60,000 was raised in the end and, in addition to letting thousands of Marillion fans see their favorite band in the flesh, it demonstrated the latent power of the Internet. This thing wasn’t just for geeks, it was a powerful beast that could unite people for shared goals.

Indeed, just two years later, a filmmaker used the Web to fund a movie called Foreign Correspondents. Some three weeks into filming, writer and Director Mark Tapio Kines had spent $40,000 of his savings, and was in debt with no money to cover resources.

“I thought the only possible chance to get money fast was to see if I could get the word out about the film,” explained Kines in a Chicago Tribune article at the time.

And so he created a website for his film, eventually going on to raise $500,000. Granted, most of the funds ended up coming from friends, family and film industry investors, but around a quarter emanated from those who learned about the movie on the Web.

“I was surprised that so many people were so eager to help a complete stranger,” explained Kines. “But I worked incredibly hard to make sure people would trust me to see that I did in fact have a finished product. I would send them the script. I would send them the rough cut. I would do everything I could to let them know that they weren’t putting their faith in the wrong person.”

The rise of crowdfunding

In the years that followed, a number of dedicated platforms sprouted up to try and harness this new-found power. ArtistShare was one of the earliest on the scene, offering to let fans fund production costs for albums sold online, with artists receiving a larger slice of the pie than they otherwise might on a traditional contract.

Check out this BBC report from 2004:

More than a decade on from launch, ArtistShare is still going strong, and recently penned a deal with iconic jazz label Blue Note, to create a lower-risk hybrid division called Blue Note/ArtistShare.

Many others have followed since then, including Sellaband and Pledgie, while more donation-based portals such as JustGiving and GiveForward adopt a similar model in terms of making it easy for multiple people to give money to single causes.

Today, you can take your pick from many, many crowdfunding platforms including GoFundMe, RocketHub, Appsplit, Fundly, Unbound, PubSlush, Indiegogo and Kickstarter. Though most of these don’t offer anything in the way of equity, other sites have arrived on the scene to cater for this, including Microventures, CircleUp, CrowdCube and Seedrs.

It’s probably also worth noting the rise in peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms such as Funding Circle, Zopa and Lending Club, as well as microfinancing tools such as Kiva. Though many of these are fundamentally based on the same principles as the aforementioned crowdfunding platforms, the goals are ultimately different. Crowdfunding is often used to fund creative projects, with backers gaining nothing in return but a warm sense of self-satisfaction and early access to the goods. Though as we’ll see in a bit, the lines are starting to blur.

The present

So here we are in 2014, and crowdfunding is an acceptable, viable and increasingly popular means of getting an idea off the ground.

The Pebble E-Paper watch is among the most high-profile crowdfunding projects in recent times, topping $10 million in pledges. Meanwhile, Star Citizen has claimed to have raised more than $30 million from crowdfunding through its own site AND Kickstarter, to (hopefully) see the Windows game eventually make it to market.

The thing with crowdfunding is, there are no real restrictions on what you can seek funds for. If you hit on something that really resonates, then it can be an effective means of getting cash without giving equity.

Last week, we reported on a campaign to crowdfund Israel’s first single malt whisky. The folks at Milk & Honey launched on Indiegogo back in October to raise liquidity to the tune of $65,000. By the close of the campaign, that goal had been smashed, with almost $75,000 in the coffers.

And, in what can only be described as a sign of the times, American animator Bill Plympton took to Kickstarter a year ago in a quest to fund a new animated feature film called Cheatin‘. Plympton’s perhaps best known for his 1987 animated short called Your Face, and his illustrations and cartoons have been published in The New York Times, Vogue, Rolling Stone, Vanity Fair and Penthouse.

Meanwhile, Ubuntu attempted to raise $32m to build a new smartphone through Indiegogo last year, and although it ended in failure, it still managed to secure north of $11m in the process, which is quite a considerable sum.

Elsewhere, Songkick launched Detour last year, a crowdfunding platform for fans to persuade their favorite bands and artists to play in a location near them, though it remains London-only for now. Interestingly, however, Detour isn’t just being used by fans. Some independent London promoters have also used Detour to kickstart concert campaigns, as it means far lower risk – it’s like a market research tool to establish demand.

Market validation

This is an interesting point to pick up on. In an interview with Indiegogo’s Danae Ringelmann last year, she revealed that in the wake of the first Indiegogo-funded Oscar-winning film, her firm had also inked a deal with Forest Whitaker’s production company – a partnership that isn’t so much about funding his films, as it is a de-risking tool.

“He (Forest Whitaker) wants to make sure all the films he’s investing in integrate crowdfunding, because of the market validation and marketing benefits,” she said. “A lot of people think crowdfunding is just an alternative form of financing – and it totally is – but that’s the tip of the iceberg. We’re becoming the world’s incubation platform, because we’re creating an ecosystem and a mechanism where social projects, businesses, (and) creative ideas rise to the top algorithmically and automatically, rather than subjectively and manually.”

In other words, crowdfunding is a great way of showing that an idea or project has legs – if the public are putting up money to support something, then this data can be shown to bigger (traditional) financiers, be it a bank or Hollywood production company, and used as leverage to garner more funds.

“I see a world where every non-profit that’s applying for a grant from a foundation, what’s going to go into their grant application is all their crowdfunding success,” continues Ringelmann. “There will be a world where venture capitalists won’t even look at potential deals unless those businesses have validated their product through crowdfunding.”

When the global masses put their money into a project, this means they’re really on to something. It’s a little like market research, and gets the big guns interested.

Back in September, we interviewed Adam Leipzig, former Senior Vice President at Walt Disney Studios, former President of National Geographic Films, and current CEO of Entertainment Media Partners. We asked for his views on how the movie industry is responding to the rise in crowdfunding.

“Studios are responding to it in a minor way,” he said. “They are throwing a lot of money at social media campaigns, and they’re looking closely at crowdfunding. There have recently been some crowdfunded movies, such as the Veronica Mars movie, that actually are studio films. The crowdfunding isn’t so much about providing money, it’s about market validation and proof of the audience.”

This ties neatly in with what Indiegogo’s Ringelmann says, but over and above all this Leipzig says the longer-term ‘word-of-mouth’ effect is just as potent.

“These people (the backers) will become the ambassadors, and evangelists, for that movie when it comes out,” he says. “I believe that crowdfunding is 40% about the money, and 60% about connecting with your audience, building your audience and creating those evangelists and ambassadors for when the project is ready for launch.”

Though Leipzig reckons crowdfunding has a big future in the entertainment industry, he says it will be more powerful for non-studio, independent movies. And funders will be able to share actual movie profits – something that traditionally wasn’t really possible through open crowdfunding platforms.

The future

Way back in April 2012, President Obama signed the JOBS Act into law, signalling a new era for fundraising in startups. Finally coming into effect on September 23 last year, the bill is designed to lessen the regulatory burden on small companies looking to raise money, and allows them to have more investors before being forced to go public. Importantly, the bill also caters for public crowdfunding to some degree, insofar as it opens the gate for equity-based crowd investing.

But first, Title II of the JOBS Act has drawn much attention, based around the rule-changes that govern private (equity) offerings. In the past, a Regulation D, Rule 506 offering was exempt from SEC registration AS LONG as it wasn’t publicized, and the buyers were qualified institutions or “accredited” investors with income over a set minimum threshold. Title II called for the SEC to allow the marketing of these offerings, provided the buyers were still accredited.

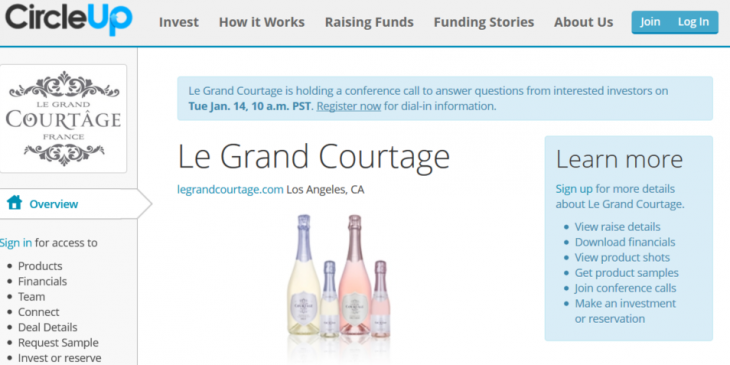

Le Grand Courtage, a French sparkling wine company, is currently raising capital on CircleUp under these new rules, meaning they can now openly solicit investors and use tools such as social media to market this. While CircleUp was always an equity-based crowdfunding platform, the fact that this can all be discussed publicly could have interesting ramifications in the future.

But why would Le Grand Courtage choosing this means to raise funds, rather than an existing crowdfunding platform and not give away equity?

“Consumer companies of this size are often too small to attract loans from banks, or are growing too rapidly for a loan to make sense,” says Ryan Caldbeck, CEO of CircleUp. “On Kickstarter, the average raise is typically $10,000. For companies like those on CircleUp, they need much more than just $10,000, and equity is often the solution.”

While we’ve shown that the likes of Kickstarter are capable of attracting multi-million dollar funding campaigns, it’s not typical. The promise of equity draws in the high-rollers, and is perhaps best suited for later-stage companies rather than those looking to merely get off the ground. “The companies set their own valuation – typically giving up 10-30% of the business for around $1 million,” adds Caldbeck.

While equity-based crowdfunding clearly has a big role to play in the future of, well, funding, will we really start seeing the big consumer-centric platforms such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo offer equity? Don’t hold your breath. At the Wired 2013 event in London back in October, Yancey Strickler, Kickstarter co-founder, addressed that very question.

“It was wild to hear folk in the Senate and Congress talking about Kickstarter a lot – my mum was excited about that,” said Strickler, when asked about the passing of the JOBS Act. “But we’re not going to do anything with that, we’re not going to change Kickstarter, we’re not going to turn it into a way for people to make money.”

But wouldn’t that be a shrewd direction to head, both in terms of tempting more backers and growing the Kickstarter platform? “I think that spoils exactly what’s special about it (Kickstarter),” he continued. “Ideas are funded out of love, not that idea of financial self-interest. I’m sure there will be ways in which it will be successful (equity-based crowd investing), but the heart and soul of what we do couldn’t be further from that.”

So that sounds like a big no from Kickstarter. But what about Indiegogo…will we be seeing equity-based campaigns any time soon? We asked founder Danae Ringelmann.

“The potential for equity crowdfunding is very exciting, and Indiegogo has been strongly in favor of it since we pioneered perks-based crowdfunding in 2008,” she says. “In 2010, we participated in running our own crowdfunding campaign to change crowdfunding law in this direction. Equity crowdfunding is a key step on our mission toward democratizing finance by allowing people not only to fund, but to invest in what matters to them.”

So, is that a yes or no?

“We certainly expect that equity crowdfunding has the chance to be a major part of our business, but we have a robust and rapidly-growing perks-based business at Indiegogo without equity already,” she continues. “Since one of the biggest reasons people turn to Indiegogo is to raise non-dilutive capital, we expect such range of needs to remain wide in a post-equity crowdfunding world.”

So, Indiegogo is non-committal at the moment, but certainly seems open to the prospect. When, or if, that does happen remains to be seen. In terms of the existing perks Ringelmann discusses, this can’t of course include money, property or any such asset. But it may include things like advanced sales of goods, discounts, coupons and gift certificates.

At any rate, even if the Kickstarters and Indiegogos of the world did want to open things up to equity, there’s still the final passing of Title III of the JOBS Act to contend with, which relates specifically to public securities crowd investing – it has been approved, but the finer intricacies have yet to be ironed out. When it’s finalized, companies will be able to raise up to $1m within twelve months, directly from Joe Public, through a crowdfunding platform. But there will be annual investment caps in placed based on income/wealth of the individuals.

“We envision a world where funding is democratized and passionate people around the world are empowered to bring their dreams to life with the help of like-minded individuals,” says Ringelmann. “The pending change in regulations to allow equity crowdfunding will certainly expand opportunities for people within the United States. We have been consistently taking feedback from our customers and the general public about how we can improve Indiegogo, as it relates to investing and other forms of fundraising, and we will continue to optimize and modify the product accordingly.”

Need for niche

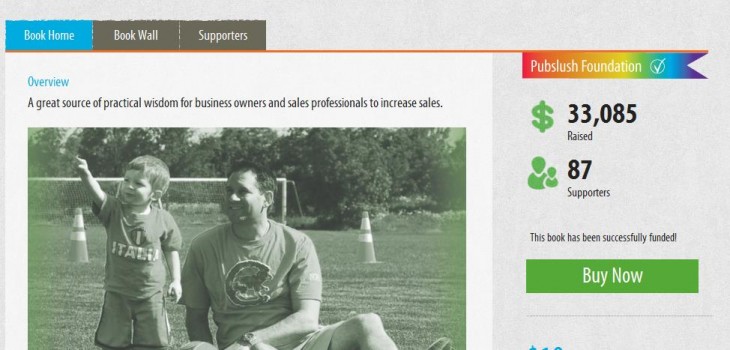

We’re also seeing niche crowdfunding platforms come to the fore, with the likes of Pubslush relaunching a little more than a year ago with a focus on book publishing, targeting emerging authors. But why the need for niche when someone could just as easily launch a campaign on Kickstarter?

“I think that we’ll see a need for more niche platforms in the next few years,” says company VP Amanda Barbara. “Why? Because I think it’s important to identify who your audience is, and know you’re going to a platform that specializes in attracting that specific audience. Kickstarter and Indiegogo are both amazing platforms, and they’re obviously doing something right. But I really do find that the struggles with these types of platforms will always be that they have so many projects going on at one time, that some will be overlooked.”

The need for niche is subtly taking Pubslush away from its bigger brethren. On the one hand, Pubslush in its most basic form is very much the ‘Kickstarter for authors’, but on the other hand it’s looking to make it easier to raise money too.

“It’s not like other crowdfunding sites, where if you don’t raise, say, $10,000 you can’t go-ahead,” continues Barbara. “A lot of the authors using Pubslush are using it as a supplement – they’re ready to go ahead with their book, they’re trying to mitigate some of their own risk, gain some momentum.”

And what about equity, will Pubslush be using the new JOBS Act regulations? “I do not see Pubslush offering equity right away,” says Barbara. “Equity crowdfunding for books would be a bit harder – unless a book were to become a best-seller, there would be equity potential. I believe the equity potential is in the movie rights for successful books.”

However this all pans out in the months and years to come, it’s clear judging by the sheer number of platforms – general and niche – and the amount of money people are putting up to support good ideas, that crowdfunding is here to stay and has a big future.

The one word we keep hearing in relation to crowdfunding is ‘democratization’. Banks and government-led schemes have long-been the source of finances for budding entrepreneurs in the past, but with billions of people connected to the Web through PCs, mobiles and tablets, the sands are shifting.

Feature Image Credit – Shutterstock | Image Credit 1 – NICHOLAS KAMM/AFP/Getty Images

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.