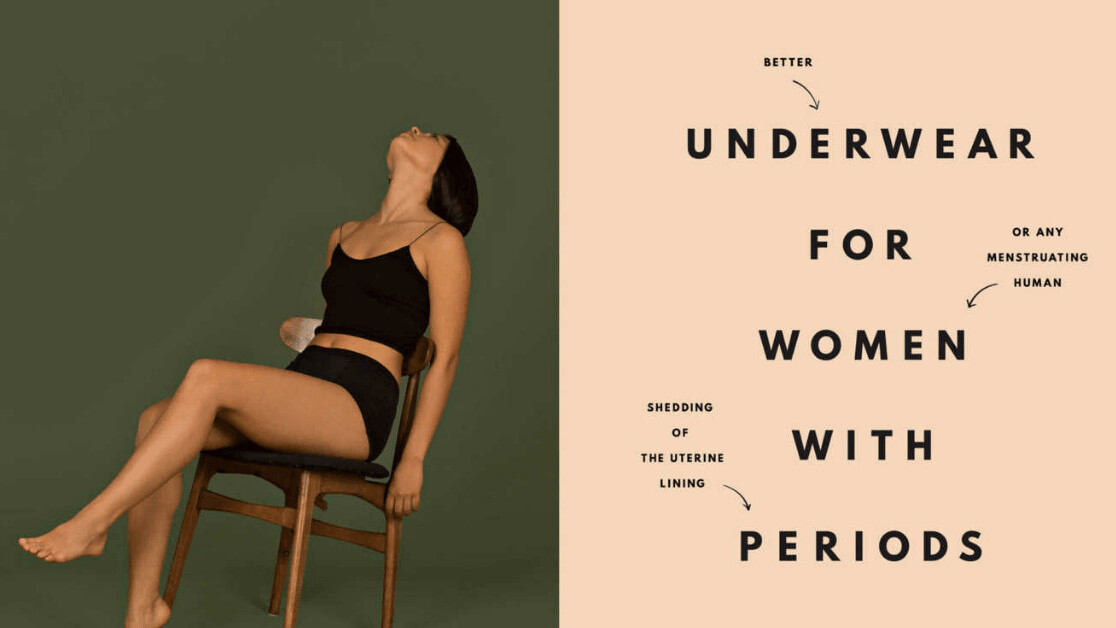

I recently watched a stand-up show in which comedian Michelle Wolf made a cunning observation: “It’s our fault we’re not further along in period technology, because we’re ok that our best solution is a rolled-up piece of cotton.”

Whether it really is women’s fault is debatable, but she does make a valid point. You would assume for a problem that affects half of the world’s population every month, we would have come up with something a little more innovative by now. Yet only little progress has been made in female health since the invention of the birth control pill in 1960.

This came as a surprise to me, considering that both pharma and venture capital are traditionally male-dominated industries. Increasingly however, women are not “ok with it.”

The last few years have seen a staggering increase in start-ups using technology to cater to female health concerns, from period tracking to fertility solutions.

Currently, 21 percent of female-founded companies are in the health sphere, a market that is predicted to grow to $50 billion by 2025. These “femtech” companies succeed in what many start-ups set out to do but ultimately fail to achieve — solve real problems.

With only four percent of overall research and development funding going to female health, most products are designed without taking the physiological differences between men and women into account.

Until as recent as 1993, women were not even included in trials for new drugs. The reason for this, you guessed it, was the fear women might get pregnant during the trial period. Even today, most research is tested only on men. And not just human men— even tests carried out on animals usually prefer male lab rats.

Yet the physiological differences between men and women are crucial when it comes to both the discovery and treatment of illnesses.

Recent studies have revealed distinctive symptoms for heart attacks in men and women and demonstrated differences in the side effects of chemotherapy. In a world that is usually quick to point out the differences between men and women, I think it’s ironic we have failed to acknowledge them in one of the few areas where they actually matter.

Our lack of knowledge about the female body results in women’s health concerns being taken less seriously than men’s. This can have fatal consequences.

Women are more likely to be told that their pain is “psychosomatic,” which is a fancy way of saying that their symptoms are simply emotional reactions. On average, women wait 16 minutes longer to receive pain medication when they visit an emergency room – from my experience, that is a pretty long time in this context.

Yet it’s not just doctors who often don’t take women’s health concerns seriously. Years of stigmatization have also had a severe impact on women’s understanding of their physical needs.

A Yale study found that many women hesitate to seek help when experiencing the symptoms of a heart attack, because they are afraid of being perceived as hypochondriacs.

Femtech makes an important contribution to combating these structural issues by demonstrating the authentic demand for products in the female health sphere. In fact, the demand is so high that many femtech start-ups, such as fertility-tracking app Woom, raise money through crowdfunding.

In addition, many femtech companies support the much-needed research in these fields. Period- tracking app Clue for example is sharing its data with leading universities such as Oxford, Stanford and Columbia.

Yet it’s not just researchers for whom this information is interesting. A lot of femtech companies perceive themselves as educators, fostering a long overdue honest conversation with women about their bodies.

At a time when women’s bodies increasingly become battle grounds of identity politics, there are few areas where the personal and the political are as intertwined as in female health.

Women are already less likely to have insurance coverage compared to men, and often pay more for their schemes. With federal funding cut from many institutions catering to female health, femtech can play an important role in making at least some health products accessible and affordable.

Michelle Wolff may be happy to hear that 88 years after its invention, there are finally alternatives to the tampon. From Flex, a patented menstrual disc to Thinx’s period-proof underwear. Many female founders are working to make “the rolled-up piece of cotton” history.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.