Certain governments have been censoring web content for years; with China, Iran and Turkey among the biggest offenders. But if there was something unique about Russia’s block of the Telegram messaging service in April, it was the extent to which the government was willing to go to.

Russia went for a wholesale, indiscriminate blocking of major cloud service providers’ IP addresses (to overcome Telegram’s attempt to port its services there). This incident exposed three unsavory truths about the modern-day internet:

Single points of failure abound

When the Russian government started blocking Google- and Amazon-based services, initial reports estimated more than 15 million IP addresses were thwarted. A long and diverse list of multinational companies, ranging from Christian Dior, to Priceline, to Tripadvisor.com, became unavailable or slowed way down in Russia.

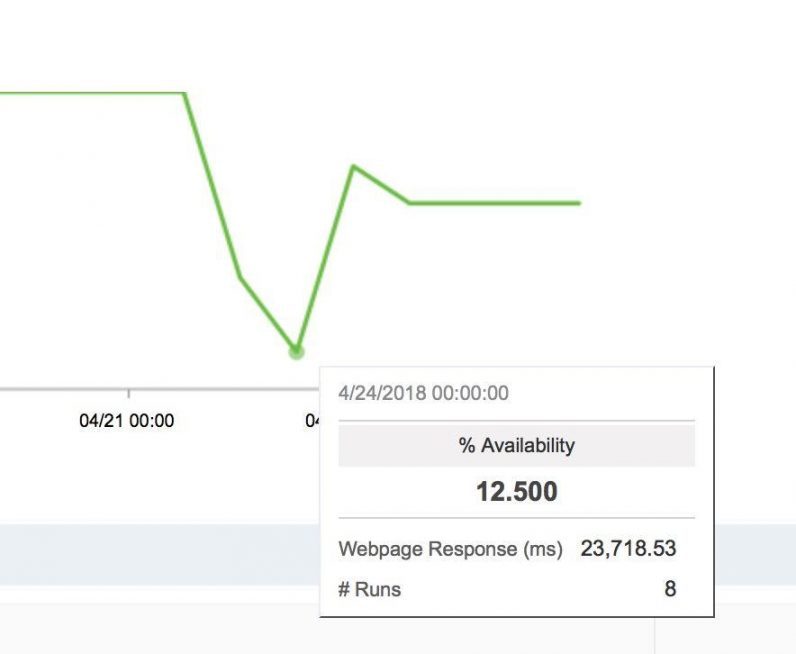

Tripadvisor.com (as the graph below demonstrates) saw its website availability in Russia drop to as low as 12.5 percent at certain intervals. When the website could load, it was taking up to 23 seconds. This poor level of performance is death to internet businesses, akin to shutting the doors of a physical store.

We take the internet’s robustness for granted, when in actuality the underlying infrastructure is like a house of cards. It’s not a matter of if another far-reaching outage like this will happen again, but when.

Any enterprise using the cloud needs to be prepared with contingency plans, including multi-cloud strategies which can enable fail-over to another cloud service provider (or internal data center) in the event of a primary cloud failure. Cloud users should also demand indistinguishable IP addresses from their service providers.

There’s a growing imbalance of power — and it’s not in the public’s favor

Coinciding with this is the fact that the lion’s share of power and control over the internet is concentrated in the hands of a very few — the largest cloud service and content providers, as well as governments. Sometimes the roles of “power grabber” and “power loser” are interchangeable, particularly in the case of cloud service and content providers.

Take for example Google — in the Russia Telegram block, Google may have been the unwitting victim, but in other unrelated instances, Google could be seen as the perpetrator. Consider Google’s built-in Chrome ad blocker, designed to weed out the most annoying ads and push website owners to stop using them.

Interestingly, Google Chrome does not block ads that run before videos on sites like the Google-owned YouTube. Is this a coincidence or a veiled attempt on the part of Google to protect their dominant share of the internet advertising pie, leveraging the user experience as a Trojan horse?

Also announced in the name of protecting and enhancing the user experience, Facebook’s Instant News service enables near instantaneous mobile downloads of news articles, and for the time being at least, publishers using the service are able to retain advertising revenues. But one can only wonder, is Facebook doing this just to be nice (doubtful), or is there a longer-term motivation here? Like ultimately pulling readers away from traditional online news sites and claiming a larger share of online publisher advertising revenues?

All of this begs the question — is the internet really a free information superhighway, or have a handful of entities (companies, governments, etc.) become too powerful — exerting, or at least vying for, control over what we see and do not see?

Censorship threatens the internet’s power as the “Great Unifier”

Government censorship of data shared with citizens has been going on for decades, to quell anti-government sentiment and maintain order. From 1945 to 1990 in East Germany, citizens needed permission to do something as simple and innocuous as displaying a visual work of art.

We tend to recoil at extreme examples like this now, but in reality, while history may not view Russia’s blocking Telegram as being on equal footing with East Germany’s censorship — at least in terms of duration — there are some common undertones.

Some would argue that in times of conflict, controlling public information that an enemy might exploit is as important as managing official secrets. This may be true, but whether we like it or not, this censorship comes with a downside, in that it undermines the unique ability of the internet to unify mankind and put everyone on the same level. This reality should be troubling to anyone with the view that the internet is and should be a fully available, open, democratized platform for ideas and information exchange.

So what’s next?

I’m not saying the Russian government is right or wrong in their request for Telegram’s encryption keys in order to fight terrorism, nor am I saying Telegram is right or wrong for refusing to comply in the name of user privacy. Both sides have valid arguments that are reminiscent of the Apple/Department of Justice legal tussle from 2016. Nor do I think that Google, Facebook, or any other big player has their eyes set on total internet domination, with every action they take directed at achieving this end.

What is clear is that we can’t be naïve anymore and continue to believe the internet is this free-flowing information resource within which everyone has equal access to participate. The nature of the internet has changed dramatically since its inception. The new net partiality law is yet another sign of this.

Established companies with deeper pockets will now be able to pay for “fast lane” internet access; how can we possibly say smaller start-ups are on an even playing field? Different countries may have different rules regarding freedom of speech, but if this is really the World Wide Web, censorship like this — in a world with single points of failure and growing imbalances of power — really needs to be a United Nations-level issue.

Russia’s block of Telegram was an example of physical borders encroaching into the digital world. On May 25, the day GDPR compliance went into effect, we actually saw many US news sites go dark in the EU — yet another worrying example. Unless this trend is reversed, further balkanization of the internet is inevitable.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.