A political sea change is emerging within the Russian Federation, and it’s all thanks to a web app.

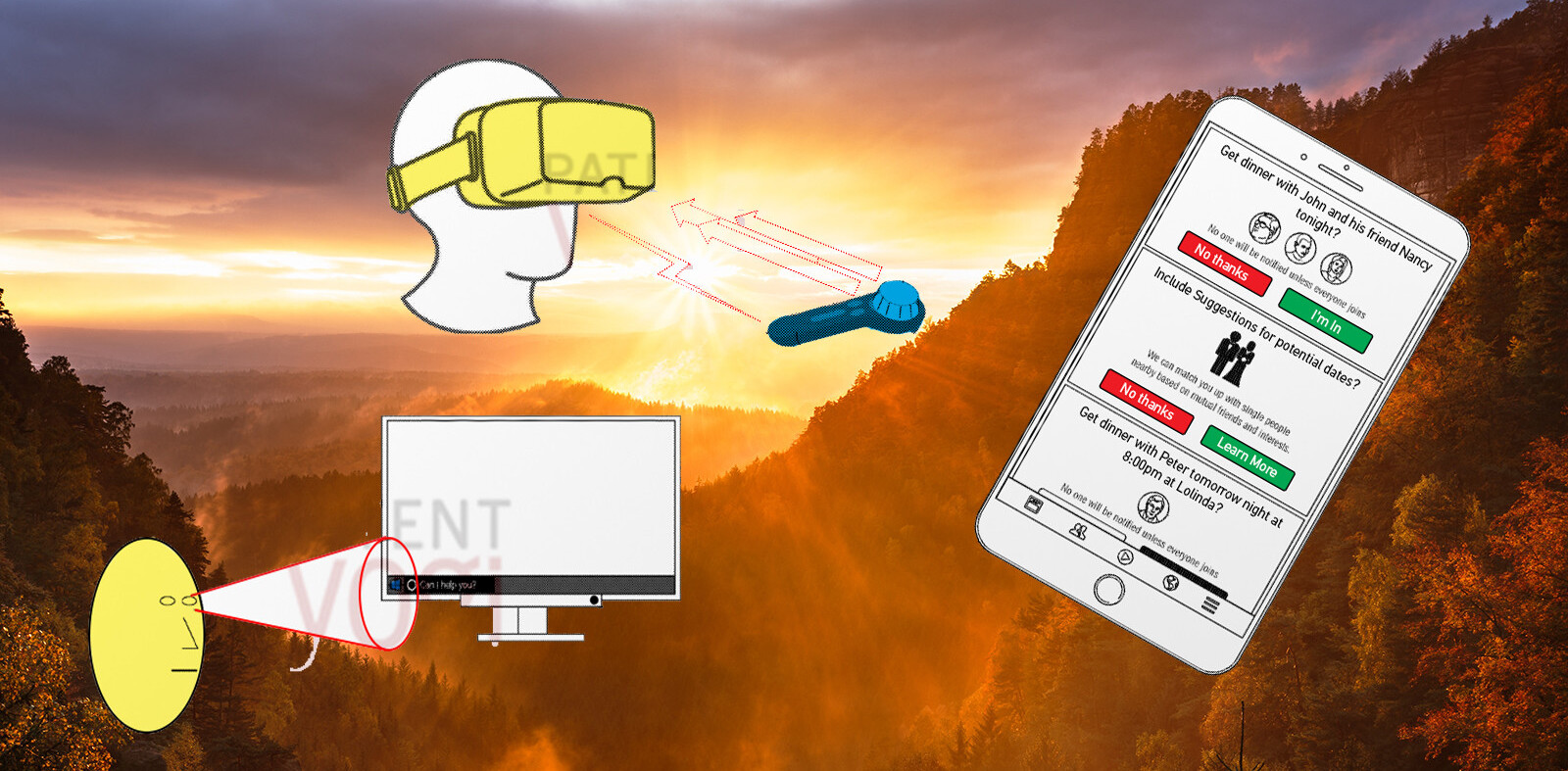

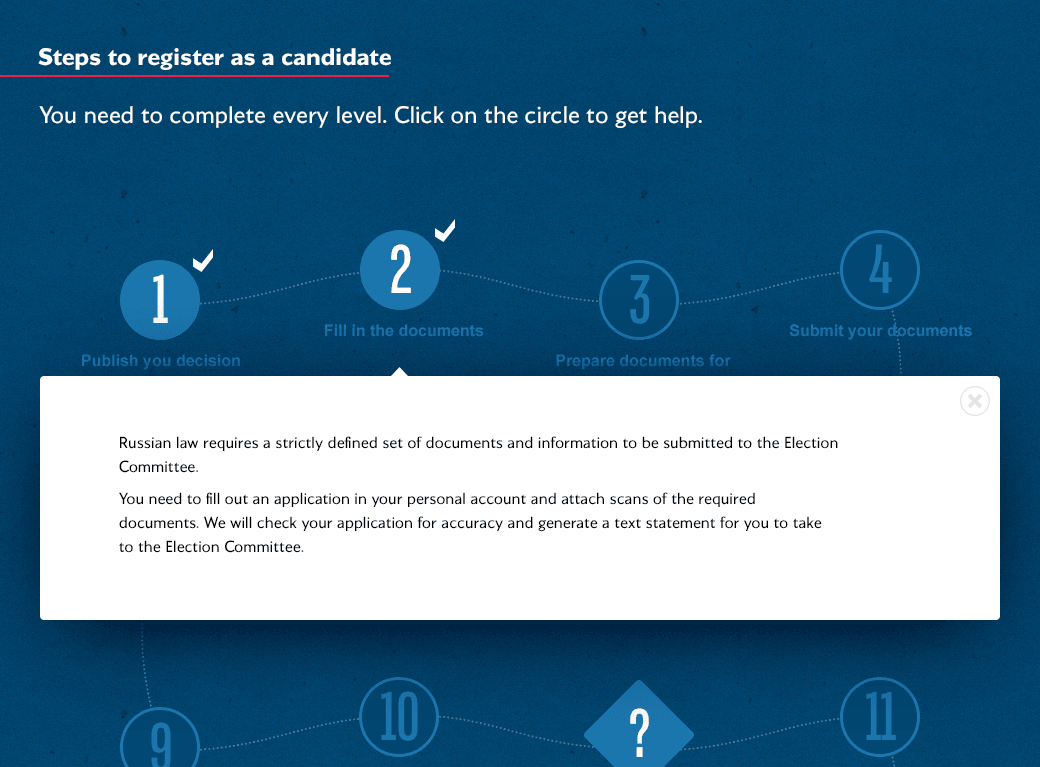

MunDep (that’s short for “municipal deputy”) is the online interface that gamifies the process of turning someone from Russian citizen into Russian political candidate. The country’s notorious bureaucracy usually keeps citizens away from participating in politics meaningfully, but MunDep presents itself as a convenient central hub for meeting a prospective candidate’s every conceivable need. It guides them through the process of filling out paperwork, collecting signatures, and printing political leaflets for distribution. When candidates face trouble of any sort, they can even chat with the human staff via voice or text.

Thoroughly cutting through Russia’s red tape, this platform turns the country’s political registration process into a 15-step “quest” for office.

MunDep is the brainchild of Maxim Katz, a former municipal representative currently focused on political technology. He operates it alongside Dmitry Gudkov, former Russian parliament member and current Moscow mayoral candidate, and Vitali Shkliarov, a former operative for Bernie Sanders’s 2016 presidential campaign. The project was announced in February this year and started onboarding candidates just a few weeks later in March. The months of effort that followed would yield some interesting results for the country’s September 10th municipal elections.

“We entered 1,054 new candidates into the regional elections and won 266 seats,” says Gudkov. “This has never happened before. Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party lost control of several Moscow voting precincts.” This includes the district southwest of the Kremlin, where Putin himself is registered to vote.

Putin surrogate and press secretary Dmitry Peskov called these results “excellent” and a demonstration of “what pluralism and political competition are all about,” but Katz isn’t buying it. “The Kremlin did everything it could to silence this election,” he says. “There was no announcement about the elections from the government, in the newspapers, or anywhere. This strategy worked against them — they didn’t expect that we’d be able to inform so many people.”

Russia faces a sense of historic indifference when it comes time for citizens to go to the polls. Gudkov says 70 percent of the Russian population is simply “not interested in politics.” The remaining 30 percent are split down the middle — 15 percent in favor of Putin, 15 percent in favor of his opponents, broadly referred to as “the opposition.” The end result is low voter turnout. Only 15 percent of the eligible electorate turned up to cast their vote this past election day.

“When I came to Moscow, I brought the experience of working for Obama and Bernie with me,” says Shkliarov. “Bernie made politics cool and sexy. Nobody cares much about the municipal level, but that’s where everything begins. This is a Sanders-style revolution for political engagement in Russia, so of course the Kremlin hates it.”

The Russian political establishment is not kind to its opponents. Most recently, Boris Nemtsov of the People’s Freedom Party was assassinated in 2015, just hours after publicly calling for a march against Russia’s war in Ukraine. The site of his murder, Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge in Moscow, commonly turns into a makeshift memorial replete with flowers and posters, but city cleaners would repeatedly dismantle these displays (on more than 70 occasions, says Katz). A leak suggested that the cleaners were acting on orders from the Moscow government.

The MunDep leadership’s attitude toward danger in the political sphere is divided. “It’s much more dangerous to drive a car in the US than it is to do oppositional politics in Russia,” says Katz. “Approximately 25,000 Americans die in car accidents every week, but not even 10 people have been killed for their politics in Russia.”

Gudkov has a more stoic stance: “Of course it is dangerous to oppose Putin and his regime, but opposition leaders don’t think of the danger. We get used to the atmosphere of hatred and threats. But I feel calm and okay because i already know you can be killed like Nemstov,” he says. “It’s better not to think about it.”

Russia’s 2017 regional elections are a compelling proof of concept for MunDep. It works effectively to get new people into office, where they can perpetuate new ideas and enact new policies. For now, the platform is aimed at municipal elections in Russia, but it’s designed to scale such that it could be used for mayoral and presidential elections in the future — even for other countries.

“It’s 100 percent certain that Putin will win his next election,” Shkliarov says. “We are not there yet. Maybe in 2024.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.