![10 websites that changed the world? They’re not what you might expect. [Video]](https://img-cdn.tnwcdn.com/image?fit=1280%2C720&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn0.tnwcdn.com%2Fwp-content%2Fblogs.dir%2F1%2Ffiles%2F2011%2F11%2FJim-Boulton-Digital-2BA49F.jpg&signature=9abe64ad4fbbb08b443b70293c92c9e1)

“The 1990s are in real danger of becoming a digital dark age”.

The Next Web’s focus shifted away from panel discussions and keynotes of Internet Week Europe (IWE), moving onto a pretty cool exhibition up in the Farringdon area of London.

Digital Archaeology is a call for urgent industry-wide action to preserve the building blocks of the Web before it’s too late. The exhibition charts the world-changing moments of the early Web, with Story Worldwide presenting “Ten websites that changed the world”…on the original machines they would have been used on at the time.

Whilst the likes of Google, Amazon, Facebook…and all the digital behemoths you know and love today are certainly game-changing, the sites chosen for exhibit probably don’t fall into the ‘well-known’ category. But they were each selected based on some milestone or innovation that helped build the World Wide Web into what it is today. In fact, you may want to check out our report marking 20 years of the Web from earlier this year.

Following its debut at Internet Week Europe in 2010, Digital Archaeology went on to be one of the key events at Internet Week New York a few months back, securing sponsorship from Google in the process and attracting 12,000 visitors.

The 10 websites that changed the world

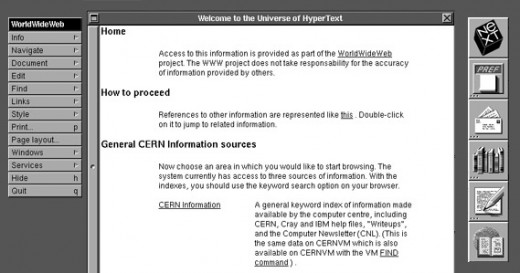

So what websites were selected? Well, first up was “The Project”, built by Tim Berners-Lee in 1991. When Berners-Lee launched this site, he also had to build a browser. This browser was called ‘World Wide Web’, which later changed to Nexus when he realized the World Wide Web was more than a browser, and the browser only worked on the now obsolete NeXTstep Operating System.

Jim Boulton tracked down an original version of this browser and reunited it with a Next Cube, the machine that Berners-Lee developed the Web on, and the oldest existing copy of the original Web page.

The Next Web met up with Jim for a guided tour of the exhibit, the video of which is at the bottom. But first, here’s a quick overview of the ten sites selected.

The Project (1991)

Antirom (1994)

The Antirom art collective was formed in London in 1994 as a “protest against ill-conceived point-and-click interfaces grafted onto repurposed old content repackaged as multimedia.” With the radical vision to explore interaction as a media in its own right rather than as an interface for content, the collective changed the face of interactive design. Built in: Director 5.

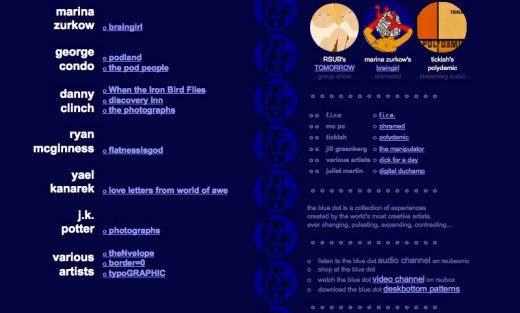

The Blue Dot (1995)

Razorfish became one of the world’s most established digital agencies partly because of a bouncing blue dot. Created out of an apartment in the East Village, its homepage used the server-push GIF-animation capabilities of Netscape Navigator 1.1 to create the first animated website — crashing many browsers in the process. Built in: HTML 2.0, Director 5 (Shockwave), Real Audio

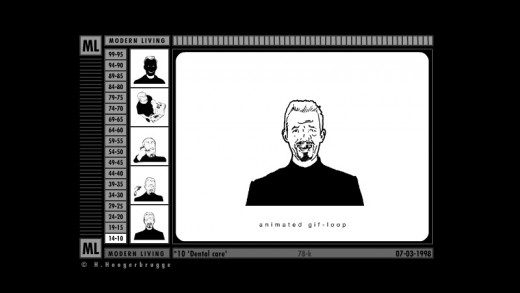

Modern Living (1998)

Starting as a comic strip in 1996, Dutchman Han Hoogerbrugge began publishing his Modern Living / Neurotica animations to his website as a series of looping GIFs in ’98. Soon afterward, he progressed to Flash, which introduced an interactive element to his

art. Built in: GIF, Flash 3

PS2 Pray Station 2 (2000)

Joshua Davis wanted to write and illustrate children’s books. After his first two attempts received two rejection letters, a friend told him, “You don’t need them anymore – there’s this whole internet thing happening. You can self-publish.” Davis went out and

bought a book on HTML and changed the face of interaction design forever. PrayStation was Joshua Davis’s sketchbook. Built in: Flash 4

Requiem for a Dream (2000)

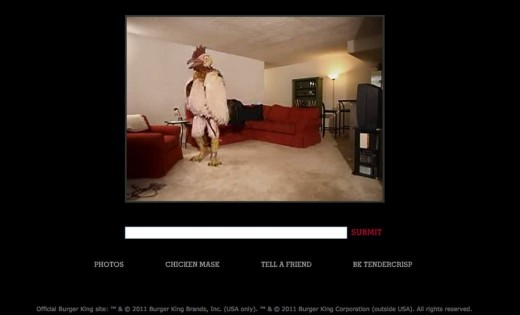

Subservient Chicken (2004)

Ad agency Crispin Porter + Bogusky wanted its creation for Burger King brought to life online, it turned to long-term collaborator The Barbarian Group. Its response was to create an interactive video-based site that allowed visitors to control the chicken via their keyboards. Want it to throw a cushion? Simply ask it. Sounds a lot like the famous Tipp-ex advert that went viral on YouTube. Built in: Flash MX

Meet the curator

“Since its invention 20 years ago, the Web has totally transformed the way we live our lives”, says Jim Boulton, partner at Story Worldwide and curator of Digital Archaeology. “Yet, tragically, many of the early websites, the building blocks of today’s always connected world, are in real danger of being lost forever and with them the stories of the unsung heroes behind them – the visionaries that invented modern culture.”

“What’s different about this show is that it’s not just about the websites themselves.” continues Boulton, “Archiving sites do exist, like archive.org, The Library of Congress’ digital preservation site and The British Library’s web archive but the sites are by necessity presented on today’s browsers, on today’s monitors and at today’s processing speeds. The context of the original site is lost. The Digital Archaeology exhibition shows the complete package, reuniting the website with the browser, operating system, monitor, computer and processing speed they were designed on and for.”

Here, Jim gives The Next Web a guide tour of the exhibit, and explains some of the concepts and technologies behind the 10 websites that changed the world.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.