The wonderful world of Twitter got a little more interesting last week after AllThingsD reported that everyone’s favorite 140-character messaging service is considering, or at least has considered, developing a standalone mobile app for its Direct Messaging (DM) service. Rumor has it MessageMe was a potential acquisition target, though Twitter declined to comment.

The general response has been less than positive. Many critics have questioned whether diversifying the product focus could distract Twitter from its core service, and doubts have been raised as to whether the app would be anything more than a ‘me too’ venture into an industry that is quickly growing.

It’s fair to say that a move into mobile messaging would’ve been more effective a year or two ago – before the biggest companies had amassed hundreds of millions of users – but there remains a very strong business case for a standalone DM app.

Increasing user engagement

The most obvious potential benefit of a DM app is to help overcome Twitter’s growth problem.

While the service is adored by those who use it, user growth is slowing and the company has a relatively modest 231.7 million monthly users, according to its S-1 registration documents. That’s significantly lower than companies that Twitter considers peers – Google and Facebook have more than 1 billion users per month each. Even messaging app leader WhatsApp weighs in with a more substantial 350 million monthly active users.

Twitter’s proposition is simple but it’s different to the rest. Facebook and Google are services that most people use almost by accident because they have become core parts of today’s online experience. Twitter, on the other hand, lacks that essentiality.

By offering a service that is relevant to anyone – messaging – and across a range of platforms, could it draw in those outside of its existing audience users? These new sign-ups might start out on direct messaging and move to Twitter’s public services – against which it sells ads – and perhaps less active users might rekindle their interest in the service after finding that the DM app had become a useful service for them?

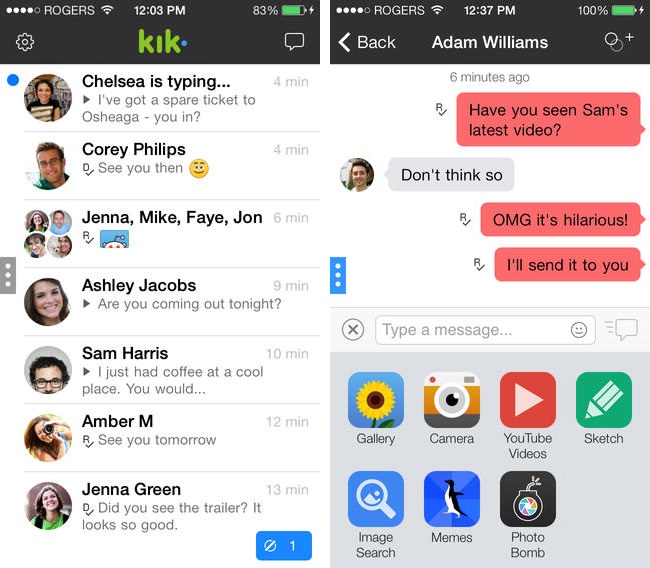

It’s impossible to say for sure. There are plenty of examples to squeeze insight from, but looking at Kik, the Canada-based messaging app that recently passed 90 million registered users (tripling its user base in under a year) and its similarities with Twitter, success certainly seems plausible.

Kik, unlike WhatsApp and others, doesn’t require users to provide their phone number to register – all that’s needed is a nickname. Assuming that Twitter retains its system of user handles (in the same way that Kik uses nicknames), it would offer a similar proposition.

Kik founder and CEO Ted Livingston recently told us that the service has “won” the under-18 market, thanks to the fact that Wi-Fi only devices can use the service. But Twitter will be more interested to hear what he had to say about the other type of users that have flocked to it:

The second group that cared about usernames were/are those people looking to connect on apps like Instagram or every mobile app with some public component. As well as great brand — ‘What’s your Kik’, ‘Kik me’ — it’s the only mainstream messenger that doesn’t require you to post your phone number.

Clearly this is an area where Twitter could play to its strengths.

If it were to follow Kik’s lead, Twitter could use its higher profile and greater level of resources to become (or at least take a shot at becoming) the private messaging app of choice for the Internet. Such a position would provide nice symmetry to its position as the Internet’s ‘global town square’ – a phrase Twitter CEO Dick Costolo uses to describe the concept of its service – and potentially beef up its pool of active users.

More than just users and engagement

If it were simply a case of potential user engagement, then it’s easy to see how folks could argue against a new product. Twitter itself is hard enough to monetize, let alone private messaging. That’s a whole new level of difficult, assuming that you want to leave the user experience untouched by ads.

But business models emerging from Asia could hold the key here.

After years of uncertainty over its business model and revenue, Twitter chose a path towards an advertising-led business model by selling its Promoted Tweets product to advertisers. This is a concept that is bearing fruit in the mobile messaging world, albeit with some adaptions.

Asian messaging firms Line, Kakao Talk, and WeChat are among those that leverage their networks of hundreds of millions of users to connect companies with audiences. They charge brands to set up and run channels which funnel private messages to users who opt-in to receive them. Typically one or two messages are sent per day.

It has been suggested that this is advertising, but that word is a little unfair since it denotes that messages are intrusive and not tailored to the individual. The correspondence is strictly consensual in the same way that liking a Facebook page permits its owner’s messages to appear in your Timeline – and that makes ‘official accounts’ on messaging apps a win-win-win for the app maker, brand, and user… each of whom gets something that they want from the process.

For example, here is Thai operator DTAC – which has amassed more than 7 million followers; a large chunk of Thailand’s 18 million registered users — and a sample of the messaging (generally phone promotions and deals) sent to its followers. I actually recently changed my phone deal based on information that I received from a Line message; it was undeniably useful.

Few messaging companies provide financial deals, but Line recorded $132 million in revenue for its second quarter of business in 2013, a 45 percent jump on the previous quarter. The company “attributed [that] to the healthy growth of its LINE [messenger] and advertising businesses,” which – alongside income from allowing brands to create and offer branded sticker packs – represented one quarter of its revenue.

That’s not too shabby considering that Line is still in the early stages of growing its global footprint.

The company has never revealed how many of its 260 million registered users actively use the service each month – it says that more than 70 million access its social network-like Timeline feature each month. Still, even using the most generous mathematics, it is probably half the size of Twitter’s active user base and far less geographically spread.

Line is doing well in a handful of markets were it has strong traction – Japan, Thailand, and Taiwan – but its chief challenge is the need to scale in every market in order to have a network that is appealing to new users and advertisers. Twitter already has traction and awareness in many parts of the world, so it could take what Line is doing and really run with the ball.

Content

There’s one final piece of the puzzle that is probably beyond Twitter, for now at least, and that’s content.

Companies like Line, Kakao Talk, and others are building their messaging apps into content platform that can deliver all manner of services, from music, to shopping, gaming, and more. Indeed, 53 percent of Line’s revenue in Q2 2013 came from in-app purchases made across its catalogue of more than 30 games.

In Thailand, for example, Line’s iOS app is out-grossing two of the world’s most successful games: King.com’s Candy Crush and Supercell’s Clash of Clans. That’s an impressive feat.

This content model, which U.S. firms like Tango and Kik are also embracing, runs in contrast to the subscription approach favored by WhatsApp, which charges users $0.99 for unlimited use for 12 months.

Gaming and advanced services require a significant amount of investment, of course, and Line – which is eyeing an IPO at a valuation of as much as $28 billion – is reportedly not making profit yet despite its impressive revenue figures.

Twitter is considering dipping its toes into messaging, and creating a content platform – while lucrative – doesn’t really jive with its motto of ‘we like to test things.’ But if the company is considering the long game, this is clearly a model that is gaining steam in the West.

The China example

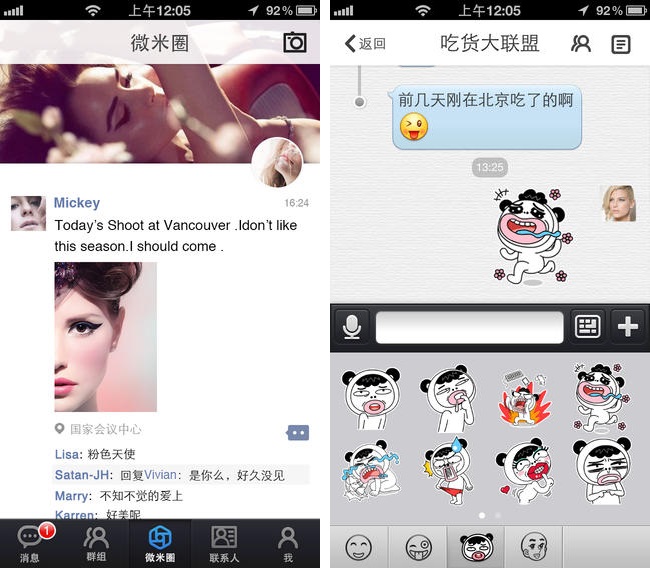

If the examples of Line, Kakao Talk, WeChat, and Kik – not to mention Facebook and its standalone messaging app – aren’t enough for Twitter, it could also look to China. Sina Weibo, loosely known as ‘China’s Twitter,’ launched its own chat app in August.

Sina’s WeMeet app is designed to bolt on to its microblogging service and challenge the likes of WeChat, a rival that is causing Weibo users to spend less time on the site. It’s focused on group messaging and social network-like features, but it largely behaves much like other chat apps.

While Sina’s motivation is different to that of Twitter – it needed to act because WeChat has become a colossus in China – the fact that a company which shares much of Twitter’s ideology has already made that move lends further credence to a standalone DM app.

AllThingsD suggested that Twitter might introduce a Snapchat-like app, but given that Facebook’s fairly blatant Snapchat clone – Poke – came and went nearly as quickly as the app’s self-destructing messages, Twitter might do better to target a broader audience with a text-oriented app that literally extends its DM service.

But…

There’s a but – of course, you knew that – and that’s (primarily) that the timing stinks.

Twitter is preparing for its IPO so the last thing it should be entertaining is a radically different strand to its business, even if it does have the potential to benefit across a number of fronts. But if the company is keen to grow both its advertising revenue and appeal to users, then a play for mobile messaging makes sense on many levels.

Aside from the question about how such an app and features would come together, there are internal issues.

Direct Messages seem to have fallen out of favor within the product team: currently the feature is pretty buried on Twitter.com and not easily navigable within its mobile apps. AllThingsD claims that the company once considered binning DMs altogether, but certainly – in today’s mobile centric world – it has a new reason to give the feature a lot more attention.

We contacted Twitter earlier this month – in advance of the AllThingsD report being published – to ask about its plans for Direct Messages, but the company declined to provide comment.

Headline image via Aina Jameela / Shutterstock (be grateful I didn’t cobble together a Twitter-meets-WhatsApp logo)

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.