This post originally appeared on the Buffer blog and has been republished with permission.

Every day it seems like we feel hundreds of different emotions – each nuanced and specific to the physical and social situations we find ourselves in.

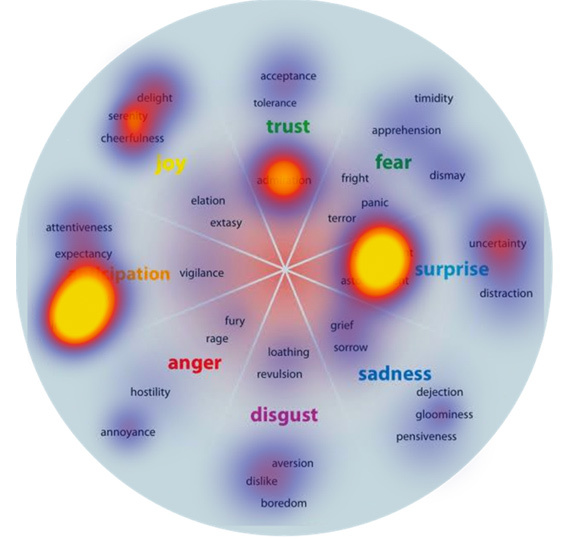

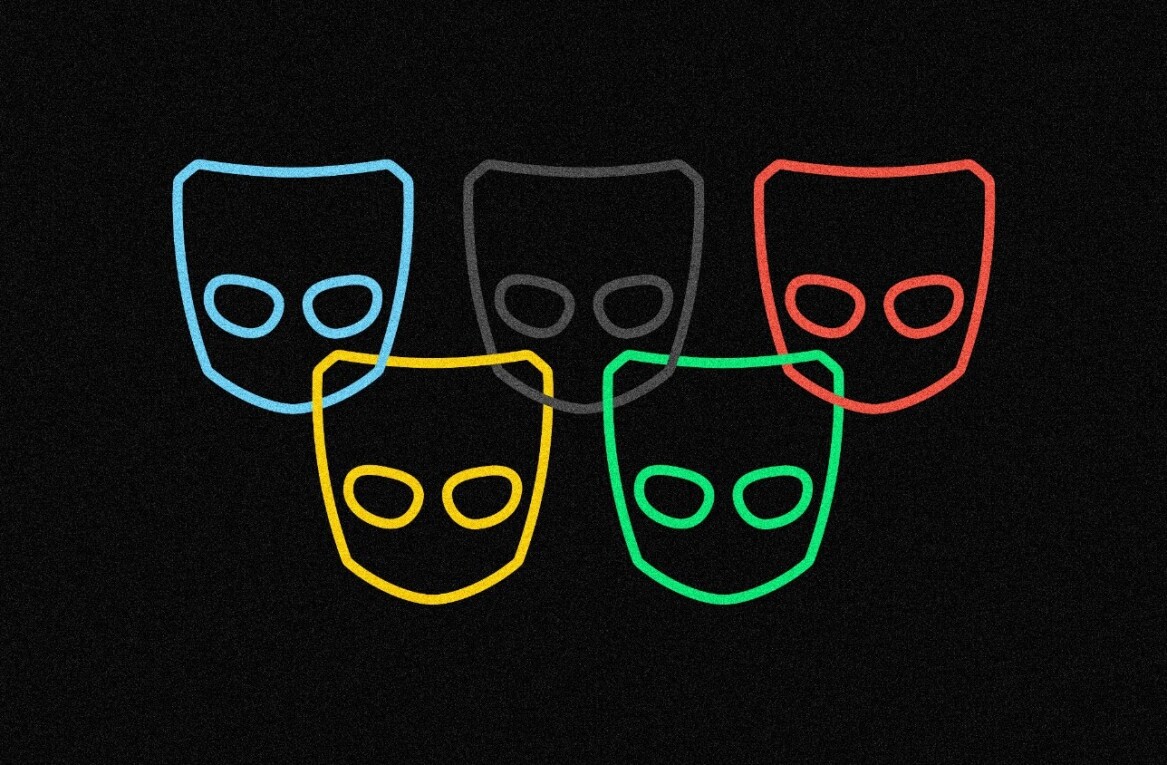

According to science, it’s not that complicated by a long shot. A new study says we’re really only capable of four “basic” emotions: happy, sad, afraid/surprised, and angry/disgusted.

But much like the “mother sauces” of cooking allow you to make pretty much any kind of food under the sun, these four “mother emotions” meld together in myriad ways in our brains to create our layered emotional stews.

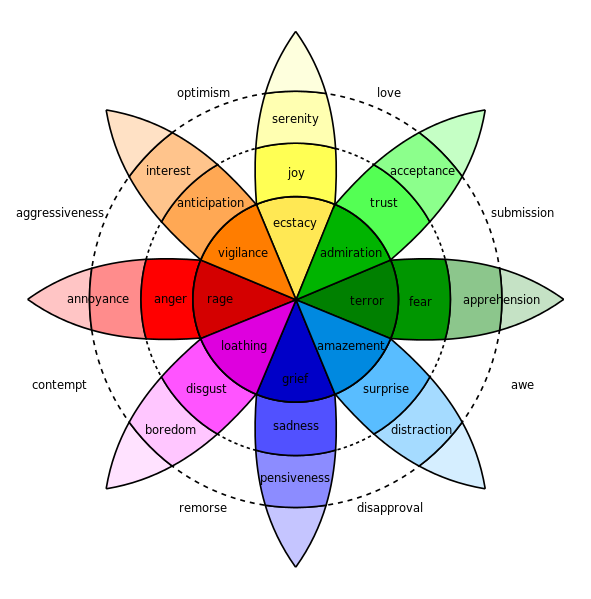

Robert Plutchik’s famous “wheel of emotions” shows just some of the well known emotional layers.

In this post we’ll take a close look at each of the four emotions, how they form in the brain and the way they can motivate us to surprising actions.

Happiness makes us want to share

Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott discovered that our first emotional action in life is to respond to our mother’s smile with a smile of our own. Obviously, joy and happiness are hard-wired into all of us.

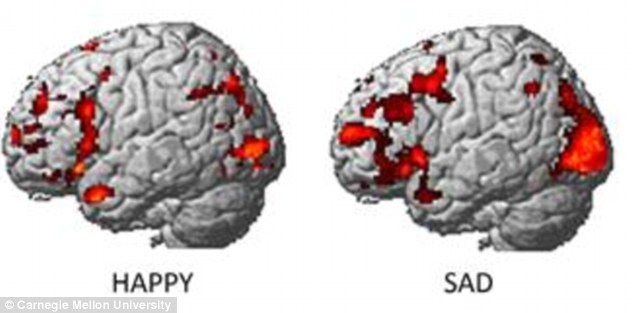

The left pre-frontal cortex of the brain is where happiness traits like optimism and resilience live. A study done at the Laboratory for Affective Neuroscience watched Buddhist Monks and found that the left prefrontal lobe of their brains lit up as they entered a blissful state of meditation.

Other than making us … well, happy … joy can also be a driver of action. Winnicott’s discovery of a baby’s “social smile” also tells us that joy increases when it is shared.

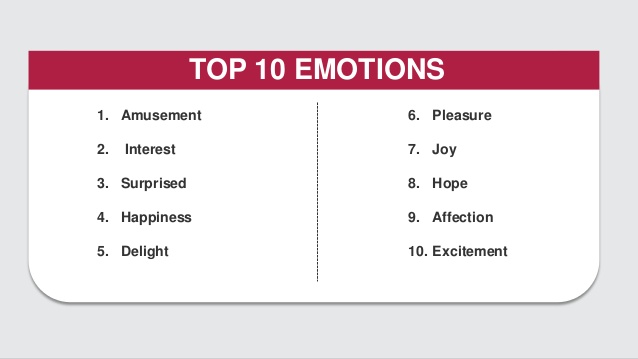

No wonder, then, that happiness is the main driver for social media sharing. Emotions layered with and related to happiness make up the majority of this list of the top drivers of viral content as studied by Fractl.

Here’s what Fractl’s study of top emotional drivers looks like overlaid on the emotion wheel:

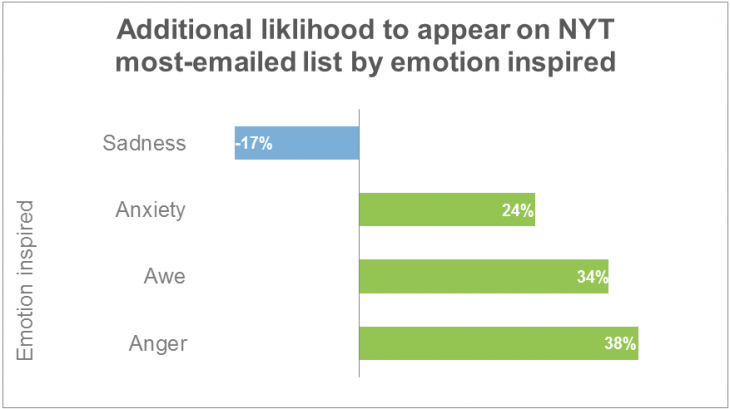

Jonah Berger, professor of marketing at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On, studied nearly 7,000 articles in The New York Times to determine what was special about those on the most-emailed list. He found that an article was more likely to become viral the more positive it was.

Google’s Abigail Posner describes this urge as an “energy exchange:”

“When we see or create an image that enlivens us, we send it to others to give them a bit of energy and effervescence. Every gift holds the spirit of the gifter. Also, every image reminds us and others that we’re alive, happy and full of energy (even if we may not always feel that way). And when we ‘like’ or comment on a picture or video sent to us, we’re sending a gift of sorts back to the sender. We’re affirming them. But, most profoundly, this ‘gift’ of sharing contributes to an energy exchange that amplifies our own pleasure – and is something we’re hardwired to do.”

Sadness helps us connect and empathize

Perhaps fitting if one looks at sadness as the other side of happiness, the emotions of sadness and sorrow light up many of the same regions of the brain as happiness.

But when the brain feels sadness, it also produces particular neurochemicals. A study by Paul Zak looked at two interesting ones in particular.

Zak has study participants watch a short, sad story about a boy with cancer.

As they experienced the story, the participants produced cortisol, known as the “stress hormone”; and oxytocin, a hormone that promotes connection and empathy. Later, those who produced the most oxytocin were the most likely to give money to others they couldn’t see.

Zak posits that oxytocin’s ability to help us create understanding and empathy may also make us more generous and trusting. In a different study, participants under the influence of oxytocin gave more money to charity than those not exposed to the chemical.

“Our results show why puppies and babies are in toilet paper commercials,” Zak said. “This research suggests that advertisers use images that cause our brains to release oxytocin to build trust in a product or brand, and hence increase sales.”

Fear/surprise make us desperate for something to cling to

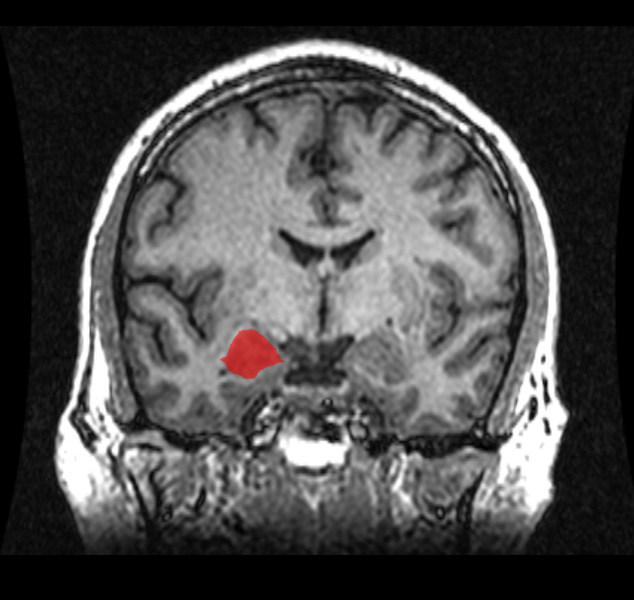

Although those who are prone to anxiety, fear and depression also exhibit a higher ratio of activity in the right prefrontal cortex, the emotion of fear is mostly controlled by a small, almond-shaped structure in the brain called the amygdala (seen below).

The amygdala helps us determine the significance of any scary event and decides how we respond (fight or flight). But fear can also cause another response that might be interesting to marketers in particular.

A study published in the Journal of Consumer Research demonstrated that consumers who experienced fear while watching a film felt a greater affiliation with a present brand than those who watched films evoking other emotions, like happiness, sadness or excitement.

The theory is that when we’re scared, we need to share the experience with others – and if no one else is around, even a non-human brand will do. Fear can stimulate people to report greater brand attachment.

“People cope with fear by bonding with other people. When watching a scary movie they look at each other and say ‘Oh my god!’ and their connection is enhanced,” says study author Lea Dunn. “But, in the absence of friends, our study shows consumers will create heightened emotional attachment with a brand that happens to be on hand.”

Anger/disgust make us more stubborn

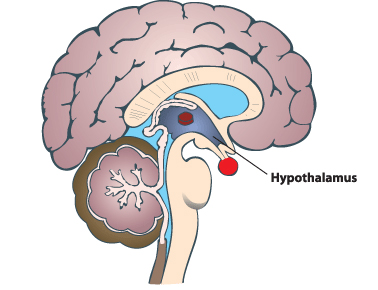

The hypothalamus is responsible for anger, along with a lot of other base level needs like hunger, thirst, response to pain and sexual satisfaction.

And while anger can lead to other emotions like aggression, it can also create a curious form of stubbornness online, as a recent University of Wisconsin study discovered.

In it, participants were asked to read a blog post containing a balanced discussion of the risks and benefits of nanotechnology. The body of the post was the same for everyone, but one group got civil comments below the article while another got rude comments that involved name-calling and more anger-inducing language.

The rude comments made participants dig in on their stance: Those who thought nanotechnology risks were low became more sure of themselves when exposed to the rude comments, while those who believed otherwise moved further in that direction.

Even more interesting is what happened to those who previously didn’t feel one way or another about nanotechnology. The civil group had no change of opinion.

Those exposed to rude comments, however, ended up with a much more polarized understanding of the risks connected with the technology.

Simply including an ad hominem attack in a reader comment was enough to make study participants think the downside of the reported technology was greater than they’d previously thought.

So negativity has a real and lasting effect – and it’s evident in how content gets shared, too. In the previously mentioned New York Times viral content study, some negative emotions are positively associated with virality – most specifically, anger.

Why emotions are important in marketing

What does all this teach us as social media sharers and marketers? That emotions are critical – maybe even more than previously thought – to marketing.

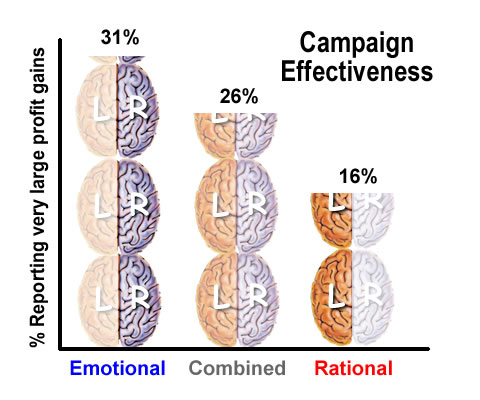

In an analysis of the IPA dataBANK, which contains 1,400 case studies of successful advertising campaigns, campaigns with purely emotional content performed about twice as well (31% vs. 16%) as those with only rational content (and did a little better than those that mixed emotional and rational content).

That makes sense based on what scientists know about the brain now – that people feel first, and think second. The emotional brain processes sensory information in one fifth of the time our cognitive brain takes to assimilate the same input.

And since emotions remain tied to base evolutionary processes that have kept humans safe for centuries, like detecting anger or fear, they’re so primal that we’ll always be wired to pay attention to them – often with surprisingly powerful results.

Like this one: In a twist on the customer survey, Generac, a standby generator manufacturer, asked some of their customers to draw their experience with the generators.

As reported in the Harvard Business review:

They saw men drawing their generators as superheroes protecting their family, and women drawing the fear of being without one like sinking on the Titanic. This exercise led them to change their marketing from technical specs to testimonials of real consumers telling their stories of how Generac saved their lives and homes. It has helped their business double in the last 2 years to $1.2 billion.

Emotion – the feeling of overcoming a primal fear – was the driver that moved their customers.

That’s why Google’s Abigail Posner says we can’t underestimate the importance of understanding the science of emotion in marketing:

“Understand the emotional appeal and key drivers behind the discovery, viewing, sharing and creation of online video, photography and visual content….In the language of the visual web, when we share a video or an image, we’re not just sharing the object, but we’re sharing in the emotional response it creates.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.