![Egypt Rebuilds as the Revolution Continues [Interview]](https://img-cdn.tnwcdn.com/image?fit=1280%2C720&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn0.tnwcdn.com%2Fwp-content%2Fblogs.dir%2F1%2Ffiles%2F2011%2F04%2Fegypt-rev.jpg&signature=48774bc3779e639b94f02de650c1829e)

A thrilling tide of updates on Twitter and Facebook drew all eyes to Egypt this January, as the world watched a generation fight to end a tyrant’s three-decade rule, spurring similar protests across the Middle East.

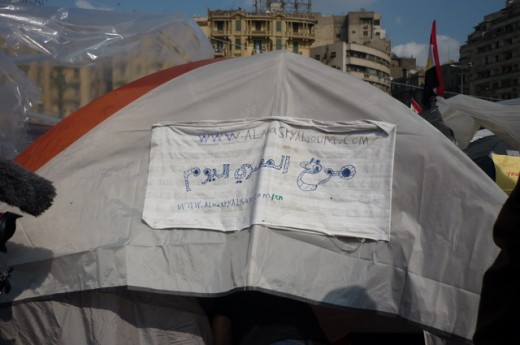

The Egyptian revolution of 2011, which began for many in the summer of 2010 and is still ongoing for some, was spurred by a series of protests demanding the forced resignation of President Hosni Mubarak after 29 years in power. While the panic has subsided for the most part, the effects of the revolution are still rippling through the country. For a purview of the revolution’s dénouement, we interviewed Mohamed El Dahshan, a freelance journalist at Al-Masry Al-Youm English Edition and a consultant in government policy, who had a great role in spreading the word during the revolution.

El Dahshan, age 27, is far from your average activist (pictured right). The self-described serial ex-pat studied at Cairo University before receiving his masters at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He later moved back to Cairo in late 2009 to pursue academic research.

El Dahshan, age 27, is far from your average activist (pictured right). The self-described serial ex-pat studied at Cairo University before receiving his masters at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He later moved back to Cairo in late 2009 to pursue academic research.

“In comparison to what we’re currently living, it’s hard to call anything exciting at that time [2009]. Early 2010 had a bit of momentum in terms of social action. Things got really fired up in mid 2010 when the police beat up a 28-year old kid in Alexandria,” he says.

Khalid Mahmoud Said Sobhi, a 28-year-old young man from Alexandria had been uploading videos that proved police were involved in corruption. Two police henchmen dragged him out of a net café and beat him to death in a crowded public street. His family member describes the scene in more detail here.

“It was pretty fucking gruesome. I thought, ‘This is real, this is happening to people like me and it could’ve been me.’ For me, the revolution started then and there,” says El Dahshan.

CBM: Describe the state of national media in late 2010, particularly when Abdel Kareem Nabil, a 26-year-old blogger was released after serving four years in prison on charges of insulting Islam, and then the months leading up to the revolution.

Mohamed El Dahshan: People have a short memory to an unforgivable extent. The government had smeared Kareem’s name, and tried to turn the public against him so his release was less impactful than it should have been. Freedom of expression aside, it’s truly frightening to see how easily the public can be manipulated and how media can be used to sway public opinion.

Before the revolution, the state media was an instrument of the regime, a bloody propaganda organism that was visible throughout the entire revolution. Things would be burning in the street and they’d be showing parks, rainbows and butterflies. We have a lot of private television networks, but we have many members of the press who are towing the line because they don’t want to upset the government. We have “opposition” or independent press; small papers, which are read by the 12 people who write them.

Egypt has 80 million people, half of which are illiterate and depend on television and radio for their news. There are a bunch of people doing wonderful reporting with a high quality of writing but they’re not talking to enough people.

CBM: Please describe the days leading up to January 25th, 2011.

MED: In late December, there were talks of a revolution planned for January 25th, which is known as “Police Day”, a national holiday to commemorate when a lot of policemen were killed by the Brits. So it seemed opportune that we’d hold a demonstration against police brutality on this day. A demonstration is usually 150 people with 3 times as many policemen. Demonstrators rapidly find themselves encircled by police, pushed and shoved. But we didn’t know what was going to happen on the 25th.

CBM: What happened on “The Day of Revolt” [January 25th, 2011]?

MED: Smartly, the organizers changed the location of the protests at the very last minute. Since it was a national holiday, everyone had the day off, and everyone knew the locations were probably fake to begin with. The actual locations were released an hour before go time so people had time to congregate before police had the roads cut off.

That morning, I used Twitter to chat with friends and figure out where people were actually gathering. There were 4-6 locations around Cairo, and about 10,000 people then converged into Tahrir Square. With 10,000 people, there was no bloody way of stopping us. We had to cross two successive bridges. The first one was pretty violent. They were waving their sticks in the air and hitting anything they could hit. But we got over the first one and by the second one, they let us get across. We were in Tahrir until 1 or 2 AM. The police were throwing stones, water guns and there was the occasional man to man fight. But late that night, the police decided to go bizerk. They shot so much tear gas you could smell it the next morning in a very open square. It was bloody disgusting. We ran in the side streets, the police brought their thugs and we ran as far as we could until we got home.

CBM: The next day, on Wednesday, January 26th, 2011, the government blocked Twitter and Facebook. How long were they down and how did you get around it?

MED: Twitter and Facebook went down around 5pm. It was more than annoying because some of us used Twitter as a primary means of communication with activists and friends; a way to check in on them to know that they were okay. We also used Twitter as a means of live reporting and sending photos to the outside world. But it was back the next morning, which in a way was funny because then people started to share information on how to circumvent the block; how to set up a VPN, use a proxy, etc. They gave us a chance to rehearse.

CBM: You knew the Internet was going to be cut off again. When did it happen?

MED: That Friday at 3pm, the Internet went dead. Who disconnects the Internet nationwide to block a protest? It was outlandish. That was a really dumb thing to do. The idea was to scare people off, sever the lines of communication between protestors and get people to panic a little bit. Mobile phones were shut off the same day. And we knew there was a good chance it was going to be ugly. Why else would they want to shut communication down if not to stop information from getting out?

That night, I woke up my half-sleepy, half-alarmed friends, “Whatever happens here we depend on you to let the rest of the world know.”

We had one small ISP that was still working because it was the ISP for the Egyptian stock market, and this one hotel was overlooked near the square and was able to hook into this ISP. Regular landlines were still working. Some people remained connected through an international dial-up. A few news agencies shared a satellite uplink. During the blackout days, journalists would report in the good, old way. They’d go out in the street, run interviews and report news on the phone to their editors who would dictate the story. My newspaper rented a suite in the one hotel that still had Internet so I was tweeting despite the blackout.

During the 4 days of Internet blackout, our Egyptian friends abroad were sending out information for us on the Internet because they knew we couldn’t. That was really heartwarming to know that you’re not on your own, even if you’re disconnected from the rest of the world.

Egypt’s Internet was restored on February 2nd, 2011.

CBM: Were you ever hurt during the protests?

MED: Wednesday, February 2nd was one of the worst days. There were hundreds of casualties. We were attacked by an army of Mubarak’s thugs, who came armed with knives and stones, riding horses and camels, which is why we call it “The day of the camels”. Someone threw a Molotov, and a friend of mine had bad burns on his hands and arms. The next day I was beaten up by an angry mob. A friend of mine lost an eye because a rubber bullet was shot straight in his face.

They weren’t like your stereotypical hippy smelly activists, far from. Everyone was on the street, they were out there on the bloody frontlines. I have a newfound respect for lots of people and lost respect for a lot of people. The people I knew during those times amazed me; for they were the most inspiring 18 days of my life.

At 6pm, on February 11th, 2011, The “Friday of Departure” the Vice President Omar Suleiman announced Mubarak’s resignation, entrusting the Supreme Council of Egyptian Armed Forces with the leadership of the country amid massive protests throughout many cities.

CBM: Now that Mubarak has officially resigned and you are rebuilding as a nation, what is the overall sentiment?

MED: It’s funny, I bumped into a friend on the street who said, “I don’t know what we’re supposed to be doing now.” She has a point. I try to read about everything that’s happening, but what are we supposed to be doing beyond that? We’re experiencing this half complete revolution.

People from the Mubarak regime are hovering over our heads as they are slowly being brought to justice. Meanwhile, Mubarak is having a holiday at our expense in Sharm el-Sheikh (aka “City of Peace,” Egypt’s premier resort city).

We’re supposed to have primary presidential elections by the end of the year, but my main worry right now is that we’ll have elections before people start finding their political bearings. If we have elections too early, the only people who will have time to organize themselves, budget and infrastructure wise, and field candidates will be The National Democratic party, (Mubarak’s party) and The Muslim Brotherhood, who are still too conservative for my taste.

We should be equally organized so that the government we elect is truly representative of the people. Every single day around the city, you have at least 2 different high-profile talks on elections and political reforms. They ask what is liberalism? What is free market? What is conservative open market? We’re in a bullying phase of political self-discovery. We’re creating parties every other week pretty much, but we’re fast forwarding a process that can take years in 6 months. There’s a smart interactive app called The Political Compass. It’s a lightweight java app that asks questions to find out where you are on the political map and it matches your answers with what would be the political party, which can be really helpful for some.

CBM: Imagining Egypt’s future, are you optimistic or pessimistic?

MED: I’m a ‘pess-optimist’. There are days when I’m elated with the political interests and goodwill out there. Pople feel energized, empowered and that they need to work for it. And then there are days when I’m much less optimistic. There are days and there are days. We’re in the middle of a learning process here. Politically speaking there’s a lot we can learn from the people outside when it comes to political organizations.

CBM: Some have called this a revolution driven by social media, in effect technology helped bring down the regime. So how are you using technology to now rebuild?

MED: People called it an Internet revolution, but it’s just not true. In fact, half of the people I was with had never used a computer. Living in a country where half the people are illiterate puts a huge limitation on the Internet’s capabilities to organize. In Egypt, Internet penetration is at 29%, but within that 29%, there are over a million Facebook users in Egypt, (out of a population of 84.5 million).

Online access is heavily skewed towards young people, which is a strength and limitation. It’s a limitation because you can’t reach their parents, but it’s a strength because you can reach the people who are the most politically active right now. So, there’s still a lot of discussion taking place online, like on Facebook pages that were also active before and during the revolution. Last month, we had a referendum on constitutional amendments, which me and all the people I follow on Twitter were very against. There’s quite a lot of talk on why people should vote no and what’s wrong with those amendments. There was a huge YouTube campaign about it.

After the revolution there was a lot of goodwill, in fact we had the highest spike in our history. Several initiatives have grown out of this like Kherna.com, which matches people who want to volunteer a number of hours of their time with organizations that are in need. One initiative I’m working on is a platform for activists. While it’s in very early stages, it will be a platform to help people build campaigns- political or not, but to get people involved. I will create or compile tutorials on how to start a campaign, use social media and have them build a website or web page at least.

To keep that newfound interest and freedom of discussion a friend of mine is starting an online newspaper called The Tahrir Square Nation. It will be only op-eds, opinion pieces and she’s trying to get a lot of high profile people involved.

On Twitter, we’ve started the #COME2EGYPT hashtag to encourage tourism, which has obviously been hurt very badly, along with our small business sector. To generally rally involvement, I started the #CairoTweetup in early 2010, and we’ve seen great turnouts over the past year.

We are still holding protests and running into skirmishes with the army. At 4am, on Saturday April 9th, the army attacked protestors [video]. From El Dahshan’s blog:

The Egyptian army, coordinating with the Central Security (the ‘amn markazy’, a branch of the police) have, 2 hours before dawn, attacked the peaceful protestors camped in Tahrir square. They fired live ammunition at them. More than 70 were wounded and at least two were killed.

When I heard what happened, I felt like throwing up. The army said they never fired a single bullet but there were people on the square then live tweeting and reporting, taking photos with their phones. We haven’t lost the touch of social media when it comes to spreading information about what’s happening. In many respects the revolution isn’t over. We haven’t put down our phones yet.

***

To keep up with what’s happening in Egypt, follow El-Dahshan on Twitter. A special thanks to our TNW reader Ahmed Faidy, who kept us up to date amid the chaos and violence in late January, and was kind enough to introduce us to El Dahshan.

Next weekend is Startup Weekend Cairo, billed as the first of events targeting entrepreneurship in Egypt, Startup Weekend Cairo is bringing together speakers, presenters and mentors from around the globe. Proof that amid the hostility and political instability, hope remains alive as Egypt continues to rebuild.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.