Facebook has shut down more than 30 accounts that were found to be spreading Remote Access Trojans (RATs) through malicious links that claimed to inform users about the ongoing political crisis in Libya.

Dubbed ‘Operation Tripoli,’ the large-scale campaign — uncovered by cybersecurity vendor Check Point Research — found that these pages have been a malware distribution point at least since 2014, potentially infecting thousands of victims.

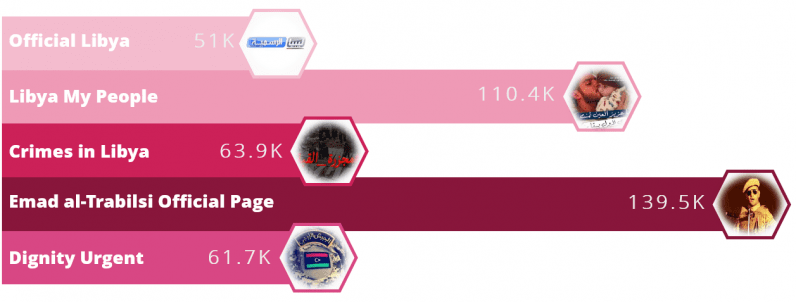

According to researchers, the accounts — some with over 100,000 followers — lured unsuspecting victims into “clicking links and downloading files that are supposed to inform about the latest airstrike in the country, or the capturing of terrorists, but instead contain[ed] malware.”

The incident serves as a reminder how social media platforms can be abused to launch malware attacks, even as companies are investing in a variety of automated and manual systems to keep malicious activities at bay.

What was the Campaign?

Researchers said they began investigating the campaign after spotting a Facebook page impersonating the commander of Libya’s National Army, Khalifa Haftar, who is also a prominent Libyan-American political figure in the country.

The Facebook page — created in April 2019 with over 11,000 followers — shared posts with links disguised as leaks from Libya’s intelligence units.

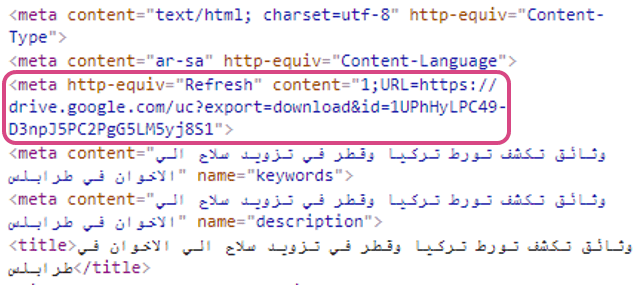

These leaks were purported to “contain documents exposing countries such as Qatar or Turkey conspiring against Libya, or photos of a captured pilot that tried to bomb the capital city of Tripoli.” Some URLs even urged users to download mobile apps that were meant for citizens interested in joining the Libyan armed forces.

But in reality, these URLs attempted to download malicious scripts and rogue Android apps that were variants of open source remote-administration tools like Houdini, Remcos, and SpyNote which grant the attacker remote access to the devices to stage various attacks.

In a further attempt to mask their true intent, the URLs were concealed using URL shortening services like bit.ly, goo.gl (now defunct), and TinyURL. Secondly, the malicious scripts themselves were stored in cloud storage services such as Google Drive, Dropbox, and Box.

But they also found instances where the attacker managed to host malicious files on legitimate websites, including Libyana, one of the largest mobile operators in Libya.

“Although the set of tools which the attacker utilized is not advanced nor impressive per se, the use of tailored content, legitimate websites and highly active pages with many followers made it much easier to potentially infect thousands of victims,” Check Point researchers noted.

The Facebook posts were found to be riddled with “many misspelled words, missing letters, and repeated typos in Arabic.” The spelling mistakes were a vital clue in confirming that the content was generated by an Arabic speaker, as they were unlikely to be introduced by online translation engines.

A lookup of some combinations of the incorrect phrasing steered the researchers to a network of Facebook pages that contained the same unique mistakes, proving that they were all operated by the same threat actor.

Who is the attacker?

The malicious script files shared by the original Facebook page were eventually traced to the same command-and-control (C&C) server with the domain name “drpc.duckdns[.]org.”

A C&C server is typically a computer controlled by a cybercriminal which is used to issue commands to systems compromised by malware and receive stolen data from a target network.

They also established that the domain resolved to an IP address that was previously associated with another website “libya-10[.]com[.]ly,” which was also used as a C&C server to distribute malicious files back in 2017.

Through a subsequent WHOIS domain lookup, the researchers ascertained that someone under the alias “Dexter Ly” had registered both the domains using the email address “[email protected].”

The alias led the researchers to yet another Facebook account, which was found to repeat the same typos discovered in the earlier pages. A closer inspection of the account’s Facebook habits also revealed that the attacker was able to get their hands on sensitive information belonging to government officials.

The Impact

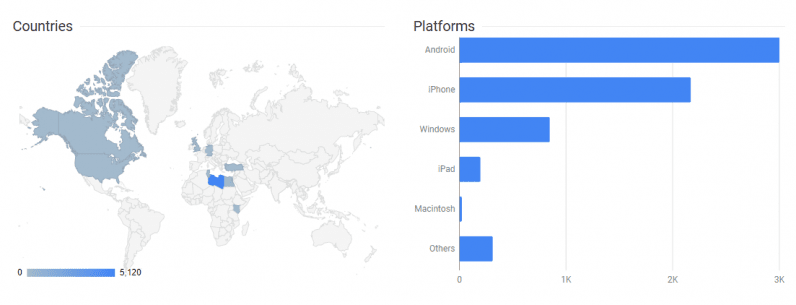

The use of URL shortening services to generate the links allowed Check Point researchers to determine how many times a given link had been clicked and from what geographic location.

The analysis revealed that Facebook pages were the most common source of the links. Most of the clicks themselves came from Libya. But it was also confirmed that the campaign reached as far as Europe, the US, and Canada. It’s worth noting here that a click doesn’t necessarily mean a successful infection.

Facebook has since shut down the pages and accounts that were distributing the malware as part of the campaign after Check Point researchers privately reported their findings.

But considering the ongoing conflict in Libya between the elected government backed by the United Nations and Haftar-led Libyan National Army, the attacker’s decision to exploit the political tensions to bait users into clicking the malicious URLs raises serious security concerns.

It also highlights how social engineering attacks are gaining sophistication, signifying that such phishing and malware threats aren’t limited to email services alone.

“Although the attacker does not endorse a political party or any of the conflicting sides in Libya, their actions do seem to be motivated by political events,” the researchers concluded.

The chain of events indicate that the threat actor leveraged Facebook’s reach, and that they were aware of what their targets were likely to click or download, thereby enabling them to spread the files using simple yet effective methods.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.