For you, I, and probably many others, LinkedIn is a bit of an odd beast. We all no doubt have a profile on the ‘social network for professionals’, but how often we actually log in and check what’s going on is another matter altogether.

Founded in 2003, LinkedIn garnered somewhere in the region of $1.5 billion in revenue last year. Today, it claims 277 million members, 3.5 million active company profiles, 24,000 schools, and 300,000 jobs. Its core mission is to “…connect the world’s professionals to make them more productive and successful”.

But blink and you might just have missed its steady shift into the publishing realm. Last month, we reported that anyone will soon be able write and share long-form articles on LinkedIn, representing an extension to its existing Influencer program.

At the Guardian’s Changing Media Summit in London yesterday, Allen Blue, co-founder and vice president of product management at LinkedIn, was in the house to talk about all things, well, LinkedIn. But more specifically, he gave some insights into what the company’s trying to achieve with its publishing hat on.

Inform. Inspire. Educate.

“When we sat down to think what we could do to make professionals better on a daily basis, we basically tacked on a few words to our mission [statement],” explains Blue. “Could we make the world’s professionals more successful by helping them stay informed, inspired and educated?”

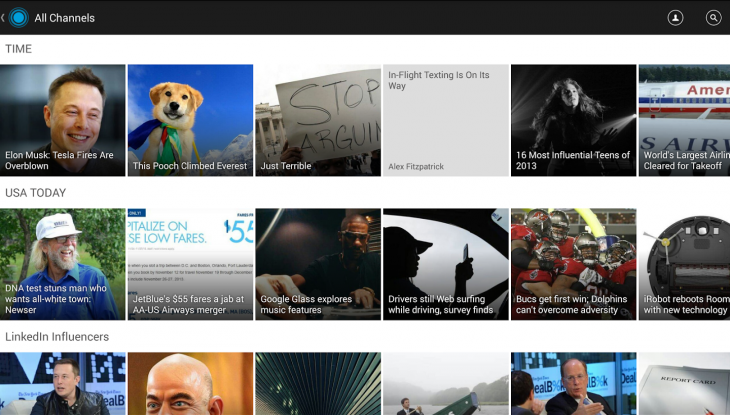

Looking through the company’s history, there are a few events in LinkedIn’s timeline you could argue were the precursor to its push towards publishing. One of those came in 2011, when LinkedIn Today launched as a news aggregator – perhaps loosely similar to something like Flipboard. You could look up topic-specific articles on things that were relevant to you, whether that’s IT, marketing or what-not.

But of course, there were key differences.

“Frankly, it didn’t have better content than any other news aggregator,” said Blue. “But the interesting thing was the way it actually worked. LinkedIn Today was not a news aggregator in a traditional sense, it was actually a social news aggregator, so when you looked at the articles that were in, say, the ‘Internet’ section, what you were seeing were a bunch of articles being shared by the people who were in the Internet industry.”

And, of Course, LinkedIn knows this because it has details from your profile about what industry you work in.

“I know this seems like a subtle point, but it’s really not”, said Blue. “In the end, it turns out that the things professionals care about most, is what other professionals are saying.”

So it’s as much about the expertise of the people you network with, as it is the content of the article itself. “We saw that, and when people heard about the way that LinkedIn Today actually operated, they got very excited about it,” continued Blue. “But we knew we could do better than that – we wanted to allow professionals to begin directly sharing information that they created with each other.”

For the uninitiated, LinkedIn’s first real foray into social, user-generated content was with LinkedIn Groups. Today, there are around 2 million groups on LinkedIn, with 100 million people having at least one Group membership. Anyone can create a Group around a specific theme or topic and invite others to join – they can then share research, best practices, statistics, or anything really.

LinkedIn’s real push towards becoming a publishing platform sought to mesh the ideas behind Groups and LinkedIn Today – professionals networking with each other, but also treating it as a news and information resource.

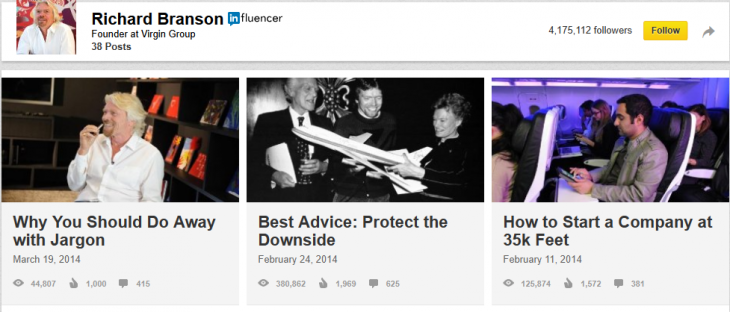

Back in October 2012, LinkedIn launched a new initiative that allowed users to subscribe to their favorite so-called “thought leaders”. The LinkedIn Influencer Programme rolled out with around 150 prominent business figures, each sharing their thoughts via long-form posts. The influencers included the likes of Caterina Fake, Andrew Chen, David Edelman, Steve Rubel, Ryan Holmes, Emily Chang, Peter Guber, Jeff Weiner…and The Next Web’s very own founder Boris.

Two months after, serial entrepreneur Richard Branson became the first thought leader to pass one million followers…double that of Barack Obama at the time, and four times that of the American President today. With more than 4.1 million followers, Richard Branson now has more disciples on LinkedIn than he does on Twitter.

While the Influencer program represented a huge step forwards for LinkedIn building its credentials as an online publishing platform, it was still very restrictive about who could post their words.

“Our original intent was to build an open publishing platform on LinkedIn, but the hilarious thing was the order in which we built it,” said Blue. “We started with building the ‘Following’ system, then decided to go out and get some famous people and maybe they’ll come ride on the platform. The amazing thing was, they were very excited about coming to write on LinkedIn.”

But how can something like this possibly scale? There’s only so many well-known, business-focused ‘celebs’ out there, and they don’t exactly have all the time in the world to pen how-to posts on LinkedIn. And this is why LinkedIn has been seeking to open the platform, and help the mere mortals of the business fraternity share their insights too.

“There are a lot of people out there who have information that they want to share, who currently don’t have as much visibility as someone like Sir Richard [Branson],” said Blue. “So a few weeks ago, we finally opened our publishing platform.”

Opened, it may be. But it’s still not truly open, in the same way as Tumblr or Medium is. LinkedIn basically invited somewhere in the region of sixty-thousand professionals from many facets of business, to come and write for it. Around two-thousand of those have opted in, with “thousands and thousands” of posts popping up on LinkedIn since.

“These people have a different motivation than Sir Richard,” explained Blue. “Their motivation is not just sharing their knowledge, but also building an audience, and building a reputation on LinkedIn.”

Indeed, Richard Branson already has his reputation firmly cemented. He doesn’t need to persuade people to listen to his every word – he has earned his stripes, so to speak. But there are many other people out there – from startup founders and investors, to marketing gurus and hacks – who have stories to tell.

“People use LinkedIn as a mechanism to represent themselves professionally,” continued Blue. “But a big way they do it, is that they can establish and prove their expertise. And a publishing platform finally opens up an opportunity for them to do that.”

But how can they possibly find an audience, if most people haven’t even heard of them? This is the challenge LinkedIn has set itself – to help those people gain an audience.

Finger on the Pulse

Pulse was always a fantastic little news aggregation service, taking your favorite websites and transforming them into an interactive mosaic. It was much like Flipboard, and for many it was actually better. But then LinkedIn weighed in with an offer to acquire the startup last year, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Now called ‘LinkedIn Pulse’, the service represents a major part of LinkedIn’s distribution mechanism. In effect, LinkedIn looks at what’s being written by people, classifies it into channels for them, and then broadcasts it out into the Pulse ecosystem. This effectively means that a lesser-known ‘Influencer’ can get a much broader reach, and it doesn’t matter quite so much if they only happen to have a handful of followers on LinkedIn.

But many, if not most, of the people who do contribute content in this way through LinkedIn aren’t bloggers or writers. And many of them have much more important things to be doing – such as running businesses. So garnering a post a day or week isn’t part of the plan here.

“Right now, our authors are averaging about two posts in the first three weeks [since opening up], which is pretty high – higher than we thought it was going to be,” said Blue. “But how do they continue to share their information and knowledge with other people in the professional world? LinkedIn is focusing not only on creating content, but also curating content.”

LinkedIn is playing a pivotal role here – it not only provides the technology and platform, it’s providing the distribution channels and curation tools too.

“If people can build audiences on LinkedIn of millions of people, it becomes a powerful mechanism for people to associate their own brands, with those folks,” said Blue. “It’s also a powerful way for publishers to publish their own content in the system, there’s actually a constellation of products on LinkedIn, all of which can be used by a publisher or a market in order to distribute content.”

A glorified public CV database?

LinkedIn has many tools at its disposal. There’s SlideShare, which it acquired back in 2012, there’s Company Pages, Groups, Influencers, and Pulse. But can LinkedIn truly shake off any lingering reputation as a glorified public database of CVs and résumés? Blue referred to “…changing people’s understanding of what LinkedIn is”, adding that they have gone to great lengths to “help people not form an opinion about what our product was, because we knew how far we wanted to go.”

Whether it can truly cement its position as a content provider and publisher, remains to be seen. But it certainly has the user-base for it, at least from a membership perspective. Getting this vast army of professionals to better-engage on the platform, and provide their insights, is another matter altogether.

This actually leads to another interesting point though. Blue was asked whether or not LinkedIn could ever conceivably start paying people to contribute – something that would certainly realign the service as more of an online journal, newspaper or magazine. While he didn’t exactly rule it out, he wasn’t overly warm to the idea either.

“It’s not something I’ve ever thought about – in order for LinkedIn to be successful in the long term, we need everyone to be part of the platform, and able to project their professional identity and participate in the ecosystem that we’re trying to build at LinkedIn,” he said. “We don’t want to set up unfair advantages or differentials within the system, which could prevent people from participating form the highest possible level.”

In other words, if they started paying some people to contribute, this would create a multi-tier system that may deter others from feeling like they could or should contribute of their own free will. It would destroy the spirit of what LinkedIn is trying to achieve. But, you never know.

“It’s an interesting possibility, [but] we have lots to prove from the publishing platform before we even consider something like that,” continued Blue.

In the increasingly democratized world of self-publishing, LinkedIn is up against it for sure. What it must do is continue to build out its brand and encourage more people to contribute – when it opens its publishing platform to everyone, we may have a better idea of what its chances of success are.

Could LinkedIn become a Medium of sorts? A Medium specifically for the business and professional world? That certainly seems to be the direction it’s heading.

Feature Image Credit – Shutterstock

Related: LinkedIn at 10: How the social network changed the way we work

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.