Last year, music streaming service Spotify partnered with Google to bundle a free Google Home Mini smart speaker for all US-based account holders with a Spotify Premium for Family subscription.

Sounds like a great way to listen to music right? But there is a catch.

There exists a laundry list of reward programs like Swagbucks, and Shopkick that lets you collect points every time you shop at one of its partner retailers, and use them to trade for gift cards at places like Amazon, Starbucks, and Home Depot. Google pays you to answer opinion polls and surveys. Even Amazon Prime is a loyalty program in the guise of a subscription bundle.

They are promotions that are meant to make you buy and use their products and services.

But nearly all of them, even the legitimate ones, are nothing but a data-grab of your personal information. These apps make it easy to earn or save cash, but in signing up for these offers, you are also opening yourself up to extensive tracking.

You might be just browsing the web or shopping online, but there exists a 200-billion dollar industry that trades precisely in that kind of data. They have become so powerful that Facebook and Google have bought their data to learn more about their users.

You see, the devil is in reading the fine print.

Customer retention as means to data collection

Loyalty programs and promotions are mostly a tactic employed by retailers and service providers to attract new customers, retaining existing ones, and prompt existing customers to increase their spending.

They are an easy means to earn freebies, or deals on products that you will buy anyway. They are also a way to lock customers into their ecosystems. And as much as these rewards and loyalty programs are convenient and enticing, there is a secret/hidden/less obvious trade-off. Even in cases where you aren’t paying in money, you’re paying for it by trading your personal information.

Some uses of your shopping information can seem innocuous enough. You give those businesses access to what you buy, and they give you discounts, or even freebies for spending money with them.

Verizon’s rewards program, called Verizon Up, lets you accrue credits for every $300 you spend towards monthly bills, and other Verizon products and services. Accumulate enough credits, you can redeem them on a variety of offers from Starbucks coffee to TV shows to movie premiers to concert tickets.

But what is not immediately apparent is the hidden cost: in order to enroll for Verizon Up, you also agree to enroll in Verizon Selects, a targeted advertising program that shares your web browsing and app usage history with other companies.

So the bigger question is what are you trading for that free cup of coffee? Is the trade-off worth the privacy sacrifice?

The multi-billion dollar data brokerage industry

As far as data collection practices go, this is where it gets murky. Most companies aren’t upfront about what kinds of data they collect and for what purpose — instead resorting to dense legalese (Hello privacy policy!) and vague phrases like “personalization” and “better customer experience.”

They aren’t entirely misleading. But this information is also used for other purposes, like targeted advertising. Retailers can also enrich the data they have collected about you from reward cards by buying customer data from third-party companies, known as data brokers.

The world of data brokers is even more opaque. California-based Acxiom is one of the largest, with over 23,000 servers collecting and analyzing consumer data, and collecting up to 3,000 data points per person – and that’s just one of the several thousand data brokering companies worldwide.

Check out this three-minute profile of the company and its business from CNN, first broadcast in 2012:

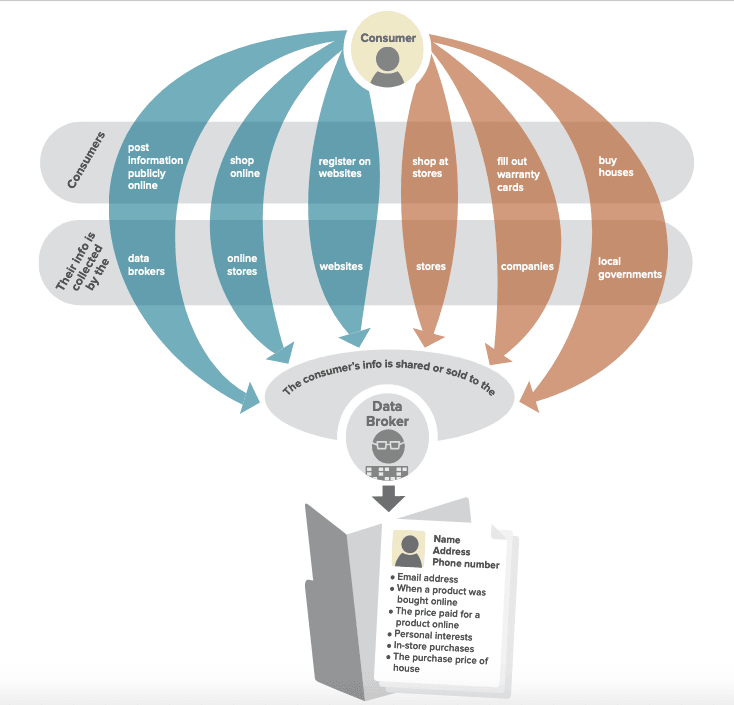

Companies like Acxiom collect consumer data from many sources, both online and offline, mostly without any consent from the people whose personal information is earning them a profit.

They can track your digital footprint as you hop from one website to another online by making use of invisible tracking pixels. They can also combine multiple datasets to build a strong profile of a person from commercial, government, and publicly available records.

“It doesn’t matter if these datasets were collected separately by different sources and don’t contain your name,” wrote Emilee Rader, an associate professor at the department of media and information at Michigan State University. “It’s still easy to match them up according to other information about you that they contain.”

Unscrupulous data brokers can go a step further and create databases by putting up fraudulent versions of legitimate websites, convincing unsuspecting users into giving up their personal information in the process.

While data brokers can serve different purposes — people search (Spokeo, Pipl), marketing (Oracle’s Datalogix, Experian, Equifax), or identity verification (ID Analytics) — it’s often difficult to identify exactly what kind of data they have in their control.

Retailers themselves can share the information collected on its customers with other retail partners, who can then use it to target ads.

The inferences drawn from such data — your credit score, real estate investments, shopping habits, annual income — also makes it astoundingly easy for a marketer or a retailer to determine if you are a targeted demographic for a rewards program.

Data mining has become a crucial tool in unearthing general patterns about consumer behavior and personalize promotions and deals tailored to individual users. In the digital age, rewards programs exist largely to justify this sort of data collection.

A database comprising of such personal data is always a competitive advantage to companies because it allows them to identify customers who are likely to stay with the brand, and even become more loyal.

What happens when data brokers lose control of your data?

Many of the modern issues with privacy stem from companies not being transparent with customers about how their data is used. Can your data be sold to companies that have no legitimate use of that information? Can it be used to deny you a job opportunity? Can it be used to implicate you in a crime you didn’t commit? Can it be used to engage in unlawful discriminatory purposes by denying you services or offers?

Unfortunately, the answer to all of these is yes.

What’s more, this isn’t including other possible consequences like data breaches and identity thefts that can make it even more difficult to control the leak of your information.

Rewards cards, for example, not only have your name, address and telephone number, but are frequently linked to partial credit and debit card information as well.

This makes it easy for identity thieves to use this information and combine it with other pieces of your data they can get from various sources. They can then go on to create an alternate identity of you, in turn using it to commit various crimes or sell it on the dark web.

Data brokers, for their part, don’t make it easy for you to opt out of such collection practices.

“Some data brokers might allow users to remove raw data, but not the inferences derived from it, making it difficult for consumers to know how they have been categorized. Some data brokers store all data indefinitely, even if it is later amended,” wrote Yael Grauer in Vice last year.

For example, your data on people lookup sites can be used by stalkers and other nefarious parties to find out where you live, or possibly call you via phone if they manage to get hold of your phone numbers.

It’s also possible they can be used against you, and for worse, denying you access to certain opportunities and privileges based on your records. Complicating the matter are situations when such decisions rely on inaccurate information available with data brokers.

Here’s the kicker though — data brokers make these databases available for cheap. A report by the Economic Times found that it was possible to get a spreadsheet of details like name, address, phone number and the classification of the card (debit, credit or a premium card) of as many as 3,000 people for just ₹1,000 ($14.39).

What can you do?

Loyalty cards and promotions are not a new thing, but the volume of data available to advertisers and companies today makes it an easy target for mass exploitation of personal information.

While retailers crafting a loyalty program need to go in with a clear strategy and a full understanding of data protection guidelines, being transparent about data collection and sharing can go a long way towards easing consumers’ anxiety.

But if you, as a customer, decide to participate in one, you can do so by taking some small steps to safeguard your privacy:

- Be mindful of the kind of information you share with companies — It’s perfectly okay to leave a field blank unless it’s mandatory. It’s also within your limits to ask why they need your personal information and what they will do with it.

- Consider using a secondary email address — If a loyalty program needs your email address, you can create a secondary email account that you can just use for such kind of subscriptions. Even better, you can mask your actual address using a service like Abine Blur. (Apple’s credit card service Apple Card and the newly announced Sign in with Apple is meant to exactly give you this kind of privacy protection.)

- Look up the company’s privacy policy — Find out what it does with your data, how long it retains that data, and with whom it shares that data. If you are downloading their apps on Android or iOS, think twice before granting them access to your location, or contacts.

- Find out how these companies make money — If you are going to use a rewards app, it’s important to understand its business model. For example, an app might make money by selling your shopping habits to an advertiser or a third-party. It might partner with retail stores or might rely on subscriptions to serve its customers. But this is also why it’s crucial to know beforehand what kind of data it collects and how it uses it.

- Opt out of data collection by data brokers — While not all these data collection companies allow you to see what they have gathered about you, some like LexisNexis, Datalogix and Epsilon allow you to contact them for full opt-out. But there is no guarantee that your personal information is permanently removed. A recent report by the Financial Times found that removing personal details from people search sites is not just “arduous,” but also that “at least one record reappears online for 45 per cent of people within four months” after they are taken down.

- Do an audit of your social media accounts — Adjust your privacy settings, and turn off access to third-party apps unless you find it absolutely essential.

Is the trade-off worth it?

Thankfully, people are becoming aware of some of the dangers associated with handing over their data. According to a survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of Wilbur earlier this April, 76 percent of Americans are more likely to join a program which collects only their name and phone number.

An almost equal number (71 percent) said they would be less likely to join a rewards program which collects personal information, including address, account information, and other sensitive data.

These data points highlight the growing concern customers have in general about sharing personal information.

This isn’t to say you should shut down all your accounts and disconnect from the internet. After all, loyalty, reward programs and the gamut of digital freebies exist so that they can benefit you by saving you some cash. But they also hinge on you voluntarily sharing your data. And once your information gets out into the public domain, you can never get it back.

In this era of online life, trading personal information for convenience seems to be de rigueur — and that’s assuming people understand they’re making an exchange at all.

But privacy isn’t all-or-nothing, and it isn’t one-size-fits-all. What matters is that you, as a user, have the ability to understand how your data is used, and control over whether it is used in a manner that’s in line with your expectations.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.