Undoubtedly the most interesting conversation I had at SXSW was with Dr Ted Berger, who is working on a brain implant to make life better for people who have problems with long-term memory – and the science behind it is fascinating.

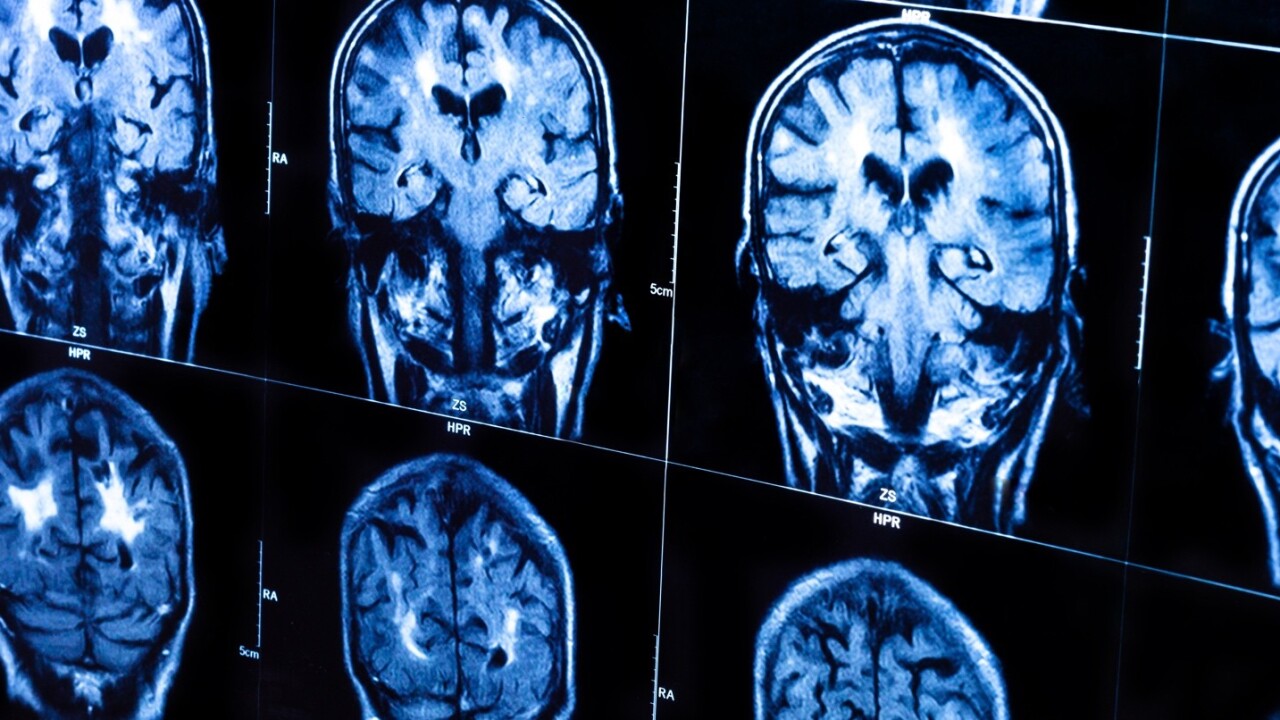

Berger explained to me how people with conditions like epilepsy and alzheimers can suffer problems with their hippocampus, the part of the brain that turns short-term memories into longterm ones.

Essentially, our initial memories of an event are binary electrical codes that are filtered through the hippocampus to another part of the brain for longterm storage. What Berger, who was at SXSW as part of IEEE’s Tech for Humanity series, is building is essentially a battery-powered prosthetic hippocampus.

Based at the University of Southern California, Berger and his team have been working with rats and monkeys to test the idea. Initially, monkeys are trained to play a game on a computer. They have to remember a symbol they were shown 30 seconds ago and click on the correct one from multiple choices.

The team then disables the hippocampus by injecting drugs into it. After this, they monitor the brain to see the electrical code it uses for the short-term memory of the symbol the monkey has been asked to remember. Electrodes are then used to ‘write’ a copy the memory into longterm storage. Berger says that it works to nearly perfect levels.

Now he’s started testing the process on human epilepsy patients with deficient hippocampuses. Although only eight humans have been tested to date, Berger says the results are positive and hardware version that can be implanted into human patients could be just a few years away.

Sweet little lies

I asked Berger if his artificial hippocampus could be used to implant false memories in people. He said that they’ve tried it with monkeys and found that giving their brains a code for the wrong symbol sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t. In related progress in the field, MIT scientists have previously implanted false memories into mice.

While Berger is working on a brain implant for medical treatment here, it’s scary to imagine that someone else may one day be able to use a similar technique to place false memories into people as a form of control (‘of course you remember how fantastic a person I am,’ says the evil dictator of the future). Maybe people could use it as a form of entertainment too. Can’t go to that great music festival? Buy a memory of it!

That’s nothing more than science fiction for now, but the very much real work of Berger and others in the field shows that the secrets of the brain and how it works are still unfolding.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.