The transportation industry has gone through significant changes over the past few years, however most of them affected rides on the ground. Uber, Lyft and BlaBlaCar, as well as newcomers like GoOpti, make it easier and cheaper for customers to get from the point A to point B.

What’s even more exciting is that the changes can also be seen in the air transportation industry, however the disruption there is developing way slower, facing more obstacles than down on the ground. One of the most interesting niches here is on-demand air travel, most often achieved with private jets.

Unlike some 10 years ago, booking a private air journey today using one of the available services can prove not much more expensive than flying first class — at least in California. This makes it an attractive option for corporate executives and business people whose job requires a lot of travelling around.

We took a look at the different models that can be implemented by the disruptive private air transportation services operating in the US and talked to three companies of different age working in the field: BlackJet, SurfAir, and JetMe.

To own or not to own

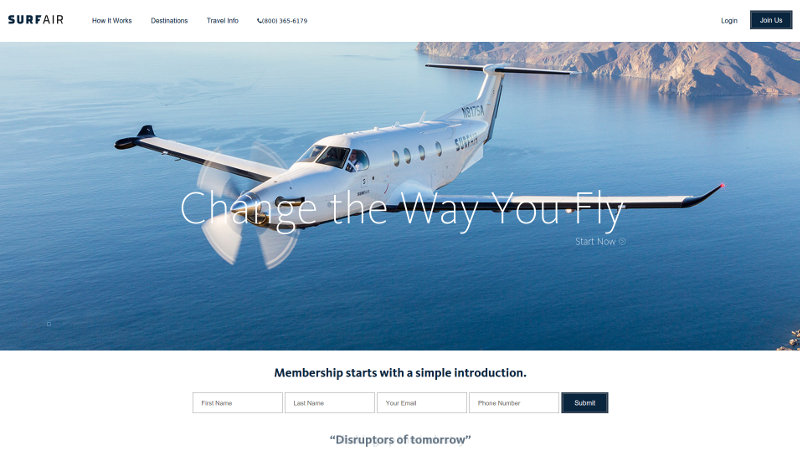

Arguably the most important choice that companies operating in the private aviation industry have to make is whether to operate a fleet of their own or work as an interface between the plane and the customer, much like Uber does. SurfAir, a two-year-old startup from California, operates a fleet of nine Pilatus PC-12 turboprop planes (pictured on the photo above) and has already ordered 15 more.

“We fly an executive aircraft with eight seats, with concierge, stress-free,” SurfAir CEO Jeff Potter told TNW. “[We charge] $1,750 a month, and you fly as much as you want. But a big, big difference of what we do versus everyone of those other carriers is the fact that we are scheduled.”

Although the model implemented by SurfAir and similar services like Beacon sounds more like a traditional airline — its flights are scheduled and you don’t get a plane all for yourself, — Potter argues that the company’s offer is unique.

The key point SurfAir focuses on is time efficiency for customers. The startup only operates in California (with additional flights to and from Las Vegas offered by a partner) but doesn’t use major airports. Instead it creates private terminals on smaller airfields, where passengers can arrive just 15 minutes before departure. What’s more, SurfAir allows customers to book a flight up to 30 minutes in advance.

Another interesting thing is the networking aspect of the airline.

“We are a membership club, and we’ve grown from 300 to 1,600 members in a year,” Potter said. “You get to travel with like-minded people. [We conducted] a survey at the end of 2014, and 11 percent of our members said they either started, consummated, or worked on a deal with fellow members that they met on the airplane.”

Although members pay for unlimited journeys every month, the average number of flights booked by one SurfAir customer is just 2.9, or one-and-a-half round trips. Occasionally some flights are full and demand is greater than supply, though normally SurfAir aims to keep its planes at 60 to 65 percent passenger capacity to ensure its service is flexible enough to address travellers’ needs.

A manually operated industry

Many private jets brokers and fleet operators, who form the core of the market, don’t have means for partners to connect to their databases to see aircraft availability.

“With three of our partners, we use an Excel file to integrate, while the information from one partner still has to be entered manually,” said Dmytro Romanyukha, Co-Founder & CEO at JetMe. “Our hypothesis is that [brokers] don’t want to optimize [their databases] because then they won’t be able to change the prices on the fly.”

“We’ve done some market research and realized that thanks to non-automated booking handling brokers sometimes increase their margin up to 50 percent of the initial price,” he added.

A year-old startup born in Ukraine and operating in the US, JetMe focuses on selling clients what’s called “empty legs,” which occur when aircraft operators need to reposition a plane between charters. This kind of flight is quite unpredictable but relatively cheap, as the operators are happy to make some money from a journey that would result in a pure loss otherwise.

An average journey between Los Angeles and San Francisco on a 6-seater with JetMe costs from $4,500 to $5,000, Romanyukha told TNW. If the journey is booked for six people, the price per person is just $833, which is about similar to what you pay for a first-class ticket.

Unlike most other industry players, JetMe doesn’t charge a membership fee, taking only a 10 percent commission from each flight. In April 2015, the startup introduced the reverse auction model, which means customers are now able to choose their dates and destination and tell how much they’d like to pay for a private jet. The system gives them the probability, with which the bid will be accepted by operators.

Romanyukha sees JetMe’s future in cutting the middle-man, i.e. the brokers, and working directly with independent pilots offering their services to passengers, effectively grabbing the ‘Uber for private jets’ moniker. This area, however, is strictly regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and currently there’s no legal way for the startup to begin doing that.

A new angle

Yet another business model in the private aviation are is used by BlackJet, a US-based startup founded in 2012. After being all but declared dead in 2013, it has been resurrected and somewhat revamped.

BlackJet customers are charged a relatively modest membership fee of $5,000 per year, although that doesn’t include any actual flying. “The seat price is very affordable,” the company’s CEO Dean Rotchin told TNW. Similarly to JetMe, BlackJet doesn’t have its own fleet, but unlike the competitor it claims to not depend on empty legs.

“In fact, [BlackJet] it is a system that eliminates empty legs,” Rotchin said. “We’re creating a route structure, we open up routes when we have sufficient customers already in the city. So, we advertise, let’s say, in New York and South Florida, and Los Angeles, and San Francisco, and Las Vegas, which are the current markets that are opened [by us].

“We have thousands of members and then we say: okay, you can fly between New York and South Florida, you can fly between New York and LA. The planes go back and forth between those markets and there’s really not a lot of empty legs. If our system works, it’s consistent travel between the major markets without a lot of repositioning, which makes the operators happy.

“We do buy empty legs from time to time because those are advantageously priced flights, but our business model is actually to create efficiency for the operators, not to rely on their inefficiency.”

Working somewhere in between JetMe’s and SurfAir’s models, BlackJet allows customers to book flights between the open destinations on certain dates in three-hour windows from 7am to 10am and from 4pm to 7pm. Then the fleet operators bid on the trips and offer their airplanes. Passengers’ seats are guaranteed immediately, although they only receive the details of when exactly they will fly on the day before departure.

“We like the idea that we have no aircraft because we’re able to create efficiency for ourselves, and flexibility in this marketplace is a lot,” Rotchin said. “Some routes are very busy some weeks and then they’re not busy on other weeks. If you have [a fleet], you’re always just figuring out what to do with your airplanes. We’re figuring out what to do with passengers.”

East or West

While the US appears to be the best market for private aviation startups to grow, while other parts of the world don’t get that much attention. The startups are sizing up the opportunities beyond North America but haven’t taken any steps to enter these new pastures.

“The US market has been growing significantly in the last eight years,” said Romanyukha. “Among other rapidly developing countries is China, which is JetMe’s priority market after the US. We expect huge disruptions in the private aviation industry in China in the next year or two.”

SurfAir is more cautious in its plans on covering other markets.

“If you start flying longer, you’re going to have to get a jet, which burns more fuel,” Potter said. “We’re certainly looking at that, but [there’s no] ability to offer all-you-can-fly for $1,750 a month when you start operating jets. You’re probably talking $5,000 [a month], if not more.”

Potter admitted, however, that SurfAir “has its eyes on” the markets of India and Middle East, with Europe being considered particularly attractive.

Rotchin mostly agrees with his peers.

“India is an interesting market,” he said. “The regulations regarding private aviation are becoming more liberal there, and that creates a lot of opportunities.

“There is also lot of demand — even from our customers, — to fly to the major European markets from New York, and one day we might envision that. But we will probably have to have $500 million in revenues in the U.S before we would ever consider opening up an overseas route unless it’s with a giant partner.”

Image credit: Bahari Adoyo / Flickr

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.