Y Combinator non-profit alum Zidisha is launching its cross-border P2P lending platform in Haiti, its first Latin American market, its founder Julia Kurnia told TNW in an exclusive interview.

According to its website, “Zidisha is the Swahili word for ‘grow’ or ‘expand,’ as in a business or a quality such as freedom or prosperity.” Prosperity is indeed the result it hopes to achieve through its crowdsourced loans, not only for borrowers but also for their home countries. Before Haiti, Zidisha’s platform was already open to projects from Burkina Faso, Ghana, Guinea, Indonesia, Kenya, Niger, Senegal and Zambia.

While loan applicants have to live in these countries, lenders are typically from more developed economies, but not just the US. According to Zidisha’s stats page, its more than 20,000 members come from a total of 144 countries.

The same page also points out that more than $3 million loan money has been raised through its platform, helping fund 13,450 projects to date. Here is a sample of some open projects:

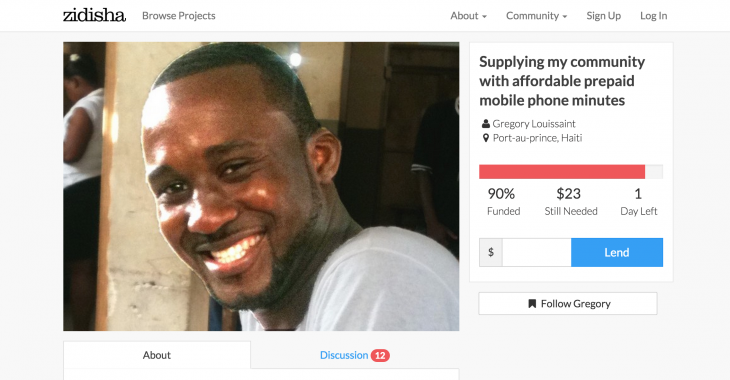

As you can see, each project has its own page, in which the prospective entrepreneur describes their needs and goals, from opening a restaurant or hair salon to buying farming supplies and computers. This isn’t simply storytelling; according to Kurnia, one of Zidisha’s differentials is that lenders can establish a connection with the person they are funding.

This is also the reason why Gmail creator and Y Combinator partner Paul Buchheit made a personal donation of $100k to Zidisha, as he explained at the time:

“Just as Airbnb connects travelers directly to hosts, Zidisha connects lenders directly to borrowers, providing not only an affordable loan, but also a personal connection, so that people are able to exchange progress updates, photos, and more. I’m a big believer in the idea that personal connections across economic and cultural divides can go a long way towards uniting all people in peace and prosperity. It’s one of the big reasons that I’ve invested in AirBnb, Watsi (our first non-profit startup), and now Zidisha.”

Removing the middleman

In her LinkedIn profile, Kurnia explains how her experience with microfinance and public organizations led her to identify some shortcomings that Zidisha is now hoping to address:

In her LinkedIn profile, Kurnia explains how her experience with microfinance and public organizations led her to identify some shortcomings that Zidisha is now hoping to address:

“At age 22 I co-founded the world’s first microfinance organization built entirely from crowdfunding capital sourced over the internet, using funds raised from Kiva.org in Senegal, West Africa. I went on to spend four years managing U.S. government grants to small businesses in Africa, gaining first-hand experience in the traditional system of development aid with all its corruption and inefficiencies.”

This inspired her to leverage “the Internet revolution” to create a new type of platform that gets rid of intermediaries. When other organizations typically rely on local partners and physical branches to source and control the loans, Zidisha’s approach is much more hands-off, both for practical and philosophical reasons.

On one hand, it is very careful to limit its overhead and costs to be as efficient as possible. As a result, its team is entirely remote, and the only two people on its payroll are Kurnia herself and Zidisha’s developer Hardik Bhadani, who is based in India.

Not only is everyone else a volunteer, but they are also expected to pay for their own expenses. “We have lots of very generous people building the community,” Kurnia says. She estimates the total number of volunteers to about 100, with varying degrees of involvement, from part-time translators to full-timers who travel to the countries where Zidisha operates.

On the other hand, Kurnia is a strong opponent of paternalism, which she sees in traditional development aid, but also in some microfinance initiatives. While others may ask borrowers to attend classes and comply with other requirements, Zidisha doesn’t directly manage the use of proceeds: “As long as it is ethical and legal we don’t tell people what to do.”

Kurnia sees this approach as more empowering for low-income borrowers. Rather than charity handouts, they are given funds that they are expected to repay — and the vast majority does. “Repayment rates on Zidisha are comparable to those of US small businesses,” Kurnia says.

Building trust

Haiti is a good example of how Zidisha vets borrowers in order to avoid payment default. Behind the four Haitian projects it featured before its official launch in the country, were four new members Kurnia had met in person during her exploratory trip last December.

Kurnia had been invited to visit Haiti by an official of USAID who had heard of Zidisha. During her time there, she recalls seeing widespread poverty and the long-lasting impact of 2010 earthquake, but also high interest for education and self-employment.

This led Zidisha to partner with two universities; ESIH in Port-au-Prince, and the Université de la Grand’Anse in the small town of Jérémie. These two entities should help spread the word about Zidisha, who can’t rely on online advertising to find borrowers: “people would think it’s a scam if they didn’t hear about it from someone they know,” Kurnia says.

In addition, connections between members are an essential element of Zidisha’s borrower vetting policy. For instance, current members are encouraged to invite their personal contacts to join, but only the most trustworthy: some benefits they can get are contingent on their friends’ reimbursement score.

One of Zidisha’s first Haitian members already signed up to be a volunteer mentor in charge of helping others join the platform, and Kurnia expects things to snowball from there. “Once we reach a critical mass of 50 people, it starts growing exponentially, because it is such a good deal for the borrower —the bottleneck being lending capital which doesn’t grow as fast,” she explains.

The power of mobile

One of the most interesting aspects of Zidisha is its reliance on mobile payment options, which are much more adapted to younger generations emerging markets. “We are piggybacking on the spread of that technology; the reason we started out in Kenya is because M-Pesa was there,” Kurnia recalls.

“In Ghana and Zambia, funds are transferred via a similar mobile phone payment service called MTN Mobile Money. In Indonesia, funds are transferred through the Indosat Dompetku mobile payment service. In other countries, loans are disbursed via electronic payment order from a local currency bank account, and entrepreneurs deposit cash repayments to the same checking account at the branch located nearest them,” Zidisha details in its FAQ.

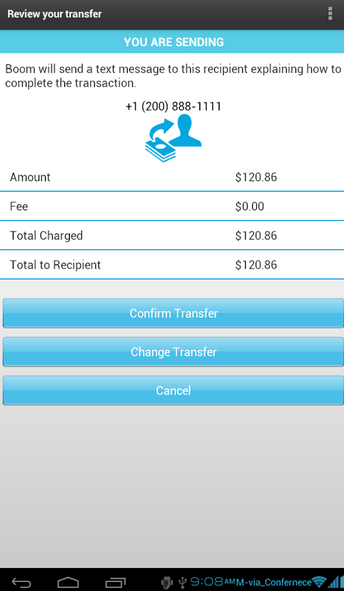

In Haiti, it ended up partnering with cash-to-mobile Boom, rather than market leader TchoTcho, which is owned by Digicel. “Boom was recommended to us. It is more cost-effective in our case and it is also more like a startup, which fits us,” Kurnia says.

In Haiti, it ended up partnering with cash-to-mobile Boom, rather than market leader TchoTcho, which is owned by Digicel. “Boom was recommended to us. It is more cost-effective in our case and it is also more like a startup, which fits us,” Kurnia says.

A non-profit at YC

Zidisha is part of the handful of non-profits that have followed the footsteps of Watsi and joined Y Combinator since it started funding philanthropic projects. “We had a hypothesis that many newly founded nonprofits could benefit from the same techniques we use to help startups. We tested this with Watsi in the Winter 2013 batch and it worked wonderfully, YC’s founder Paul Graham wrote at the time.

Zidisha’s team first heard of this opportunity through one of its advisors, SF-based Dropbox engineer Ronnie Cheng. At the time, they saw it as another grant to apply for, but the reality sunk in when the application got accepted. For Kurnia, whose husband couldn’t leave his job on the East Coast, this meant relocating to Silicon Valley for three months on her own… with her toddler, with whom she ended up sharing a bunk bed in an Airbnb flat.

Despite the personal sacrifices, Kurnia is adamant joining Y Combinator was worth it. “It was obviously a very tough decision, but the impact on Zidisha was transformational,” she says. Among other things, she used the program to learn how to code; she now handles the front-end of Zidisha’s website, which has been entirely rebuilt to be able to scale.

“YC also helped us with lots of technology on fraud prevention. We used to do many of those checks manually, and the team helped us automating that by finding us the right partners,” she adds.

What’s next

Zidisha’s culture reflects this interest mix of startup culture and philanthropy. For instance, it doesn’t shy away from describing itself as “an eBay-style decentralized platform.” Thanks to this disintermediation, it boasts microloans that only cost under 10%, well below the global average of 40 percent.

This costcutting also means drastically cutting down on travel, including to the countries in which it operates. Still, Kurnia hopes to go back to Haiti sometime during the next year. “Haiti is a bit closer so it is not that expensive as visiting Kenya, for instance,” she explains.

In the medium term, Zidisha might also expand into other Latin American countries, starting with the ones where mobile payment is more mainstream. As for languages, Kurnia says that both Spanish and Brazilian Portuguese have the advantage of being widely spoken. “Translations have been a challenge for us in Indonesia. In Haiti, we will be using the Google Translate API and a team of human volunteers to add an English translation of the loan profiles for anglophone lenders.”

Despite the language barrier, Kurnia is hopeful lenders will understand the difference they can make for Haitian self-starters. “It is a very low-income country, which means loans can go a long way,” she concludes.

Image credit: Zidisha

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.