Update: LinkedIn has now responded to concerns about the way its mobile app transmits data from your calendar

The LinkedIn mobile app for iOS devices collects full meeting notes and details from your device’s calendar and sends them back to the company, The Next Web has been informed. The information is gathered without explicit permission by a feature that allows users to access their calendar within the app.

This raises questions about how the LinkedIn app is abiding by Apple’s own privacy guidelines, as well as basic security protocol. The transmission of data was discovered by Skycure Security researchers Yair Amit and Adi Sharabani, who discovered it as a part of ongoing investigation and will be presenting the discovery at the Yuval Ne’eman workshop in Tel Aviv later today. They reached out to us with the information earlier today.

The calendar viewing feature is completely opt-in for the user, which is appropriate. So if you have not enabled the feature, it will not send anything back to LinkedIn.

But, after it has been enabled the app reads the data from user’s calendars, including any notes and details recorded. This includes both personal calendar entries and ones that may be for work.

Basically every calendar entry for the next 5 days is collected and sent back to LinkedIn every time you open the app. This includes: the meeting’s title, organizer, attendees, meeting times and, most importantly, the notes attached to the email. Note that names and emails are sent even for those entries which are not attached to any LinkedIn account.

The images above are the ‘opt-in’ and ‘opt-out’ screens inside the LinkedIn iPhone app. Note that the dialog does not explicitly inform users that they are going to be transmitting nearly every piece of data associated with the meetings scheduled.

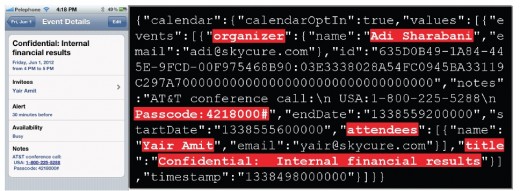

Amit and Sharabani have demonstrated their findings using the sample entry below. This shows the meeting and the transmitted information. Note the meeting’s dial-in passcode and meeting title, along with its organizer and attendees.

The researchers point out that none of the information being transmitted appears to enhance or even enable LinkedIn’s professed goal of synchronizing the people you meet and their profiles on the service. The site’s identifier for the user is the most it would need, and only other professionals on LinkedIn would be the likeliest subset.

Not only that, but the information is being sent in plain text, not cryptographically hashed, as it absolutely should be. A cryptographic hash is a method by which a developer can record user data in a form that is unreadable to anyone. Instead of storing it in regular text, they are hashed against a value, creating a string of numbers and letters. The two values, one on the device and one on LinkedIn’s servers, can be compared in order to make a match.

After it was discovered to transmit contact data earlier this year, the personal social network Path quickly began hashing and anonymizing the data it was sending.

Note that Path also kept the data it was collecting, through an apparent oversight. It’s not clear whether LinkedIn is also keeping the information stored after it has been used to make a match. The issue grew when it was discovered that many other iOS and Android apps also transmitted data.

If you’re concerned about the issue, you can open the LinkedIn app, click the LinkedIn icon in the upper left corner of the screen, tap the settings icon, click on ‘add calendar’ and toggle off the option. If you haven’t explicitly enabled this feature, then you’re fine as no information will be transmitted.

Amit and Sharabani contacted LinkedIn with this information but say that, as of today, the issue still exists. LinkedIn, for its part, replied by saying that its Privacy Policy and User Agreement covered this kind of data transmission. The researchers responded by saying that, according to their understanding, LinkedIn’s “privacy policy does not cover collecting and sending this type of sensitive information.”

They then recommended that LinkedIn not collect information that it did not need and offered their assistance in fixing the issue.

It’s unlikely, given its reputation, that the service is using it for any nefarious means.But, honestly, there doesn’t seem to be a reason for the service to collect all of this information. However, there should be more transparency surrounding what information exactly is being sent and simple steps need to be taken to send what information is necessary more securely.

We have reached out to LinkedIn for comment on the matter.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.