In 2016, “fake news” entered our collective lexicon, bringing an instantly recognizable term to something that has existed for ages.

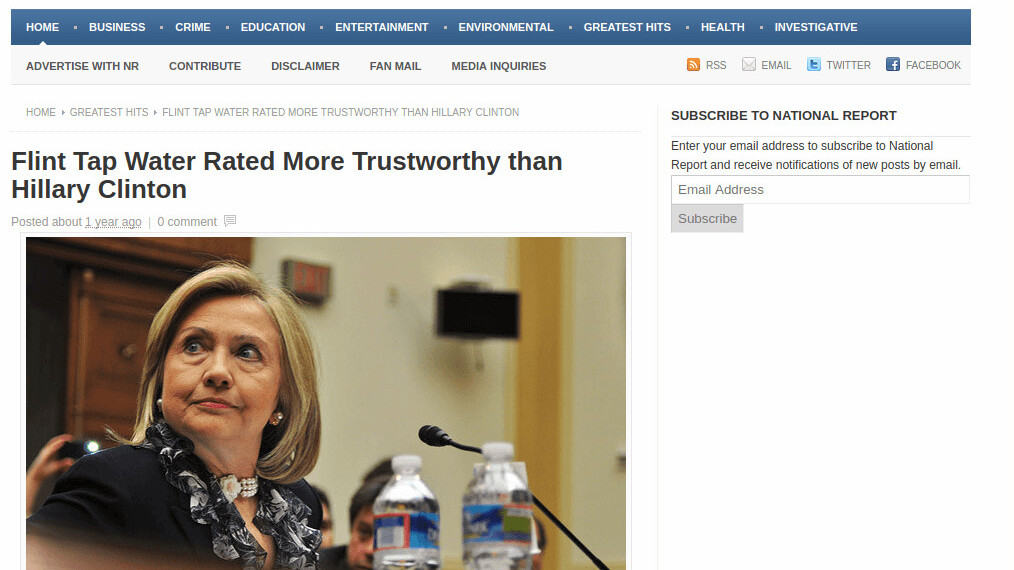

Hoax articles are nothing new. Publications like the Weekly World News and the Daily Sport have long filled their pages with fabulously implausible stories, like “Kim Jong Un is a space alien.” But this was something different.

On both sides of the political divide, the 2016 election was filled with hyper-partisan faux-reporting. Pope Francis, for example, purportedly endorsed both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders.

Many have attributed the deluge of fake news to the stunning victory of Donald Trump over his Democratic opponent. I’m not sure how much stock you could put in that, but for those living in titanium-plated filter bubbles, it certainly reinforced their support for him.

Many technologists have rightly recognized that fake news is bad for our democracy. In response, they’ve created their own tools to fight it.

You can’t dispute their intentions. I think fake news is something most of us would like to see disappear for good. But is tech able to fix what amounts to a flaw in human nature?

If you talk about the role of fake news in the 2016 election, you can’t help but talk about Facebook. Many of the false, hyper-partisan news stories found their audiences through the social giant, and even outperformed stories from legitimate news outlets. These stories were so viral, then-president Barack Obama implored Zuckerberg to take action.

At first, Mark Zuckerberg was openly disdainful about the possibility fake news on Facebook played a meaningful role in the election. He later admitted he misunderstood the impact of it, and Facebook resolved to take action.

In December, the site started to mark fake news stories with a striking red flag, and pointed readers to fact-checkers like Snopes, which disputed the factual accuracy of the story.

It was a simple fix. It didn’t work. In fact, it had the opposite effect. In our polarized political landscape, it actually “entrenched deeply held beliefs.”

“Academic research on correcting misinformation has shown that putting a strong image, like a red flag, next to an article may actually entrench deeply held beliefs – the opposite effect to what we intended,” wrote Facebook product manager Tessa Lyons.

Instead, Facebook is showing fact-checked “related articles” next to these stories. This doesn’t merely undermine the premise of the false story, but it also introduces the reader to credible journalism. That said, I wonder how many will actually click through.

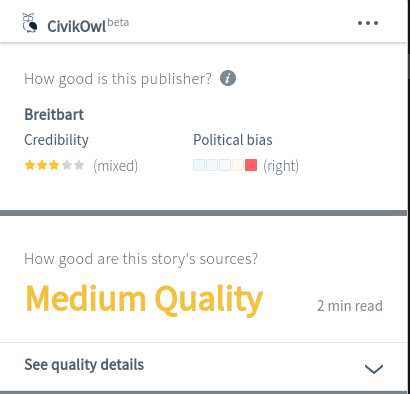

Facebook isn’t the only tech company taking aim at fake news. One of the more interesting efforts is CivikOwl, which is based in San Mateo, California.

CivikOwl’s product is a browser extension. When you visit a news site, it tells you its political leaning, and how credible it is.

For example, CivikOwl gives the BBC five stars for credibility, while Breitbart gets three. It perceives the BBC as having a slightly left-of-center bias, while Breitbart is marked as having a firmly right wing bias.

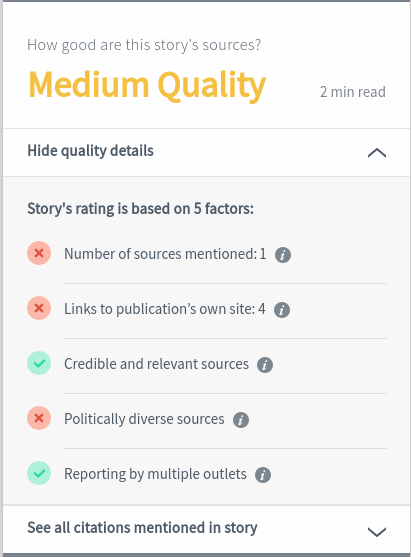

It also performs an analysis on the story you’re reading, which tells you about the quality of its sources.

This examines several different factors. The number of sources mentioned is hugely important, but it also looks about the political diversity of these sources, and their credibility.

CivikOwl penalizes articles if too many links are to the publication’s own site. So, if you’re reading a BBC article that contains four links, and they all lead to other BBC articles, that’s bad.

The argument for this is ostensibly reasonable. If a site only links to itself, it fails to expose its readers to alternative perspectives.

However, I feel as though it’s a little naive. It fails to recognize the fact that publications like the BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, and CNN all employ legions of reporters.

Looking at the BBC alone, in 2016, a Freedom of Information Act request showed it employed 3,877 people with the word ‘producer’ or ‘journalist’ in their job title. Many of these will focus on a single issue, like healthcare, technology, or domestic politics.

Why would a news website link to another publication when they’ve published their own equivalent story? Aside from being bad business sense, it sends a tacit message that perhaps the publication doesn’t have the utmost confidence in their own reporting.

There’s also the question of who CivikOwl is for. If you’re concerned about the quality of the content you read, then it’s unlikely you’re the target audience for hyper-partisan fake news. By its very nature, fake news targets the undiscerning.

CivikOwl isn’t the only player in this space. Scouring Product Hunt, I came across an array of anti-fake news tools. Most (like Fake News Monitor, B.S. Detector, and Stop The Bullshit) took the form of browser plugins.

Sadly, these combined efforts have seemingly failed, given the pervasive existence of fake news.

Five days ago, BuzzFeed editor Craig Silverman (who is one of the more prolific reporters in the fake news space) published a round-up of the most popular false stories on Facebook in 2017. The top story (“Babysitter transported to hospital after inserting baby in her vagina“) saw over 1.2 million engagements. Most legitimate websites would kill for those kinds of numbers.

So, fake news is going nowhere. Perhaps we’re going about it the wrong way? It seems like we’re using tech to plaster over what’s tantamount to a fundamental defect in human behavior.

As humans, we seek out perspectives that align with our own. This isn’t distinct to the internet. It’s just a fact of life. Fake news is media that fits our own personal biases, but unburned by the niggling issues of facts and reality — like an Oculus Rift version of Fox News or MSNBC.

In many respect, using tech to fight fake news is a bit like taking an asprin when you’ve got a cold: it addresses the symptoms, but fails to do anything about the underlying cause.

It’s not clear where we go from here. Google and Facebook are taking the fight to the sites themselves, cutting them off from precious advertising revenue.

It’s interesting to see how nations are fighting fake news. Germany plans to use the long arm of the law to fine social news sites that fail to act against fake news. If Facebook and Twitter don’t remove “obviously illegal” posts, they could face a €50 million ($60 million) fine.

Meanwhile, a proposed bill in Ireland takes aim at a favored delivery method for fake news: bots. Opposition party Fianna Fáil wants to see those that use internet bots in order to influence debate locked up for as long as five years.

Ultimately, any cure will require the following: clever technical solutions to stop the spread of fake news; efforts to cut fake news publications from revenue sources; and legal sanctions against those that intentionally try to mislead the public, in order to shape public debate.

You need all three. Tech alone isn’t enough.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.