Carlos Eduardo Espinal is a partner at Seedcamp, an early stage mentoring and investment program that engages startups through monthly Seedcamp Events.

I’ve been fortunate to have been part of over one hundred founders’ journeys from developing their initial idea to raising investor money for scaling. As such, several of these founders shared with me their stories in deciding whether to persevere with an idea, or pivot into something new.

Some of the most inspiring stories have been those where the founder has overcame difficulties with their original idea, but equally inspiring have been those stories where a pivot has led to something new and better than the original idea.

In the words of Albert Einstein – “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

One of the most powerful quotes on the subject of moving onto new things, comes from Seth Godin’s book called “The Dip“:

Extraordinary benefits accrue to the tiny minority of people who are able to push just a tiny bit longer than most. Extraordinary benefits accrue to the tiny majority with the guts to quit early and refocus their efforts on something new.

In both cases, it’s about being the best in the world, about getting through the hard stuff and coming out on the other side.

Update: Here’s Carlos’ TEDx talk on the theme of this post.

On new beginnings

If you knew that by changing one aspect of your project, or moving onto a new project (leveraging the experienced you gained working on your current project) would be better for you, would you do it?

One of the best stories out there about how a tough time was made into a success is the story of Twitter. It’s best to simply watch the video and hear it directly from one of the early employees, but suffice it to say, the founders are much better off for having made that leap of faith onto what has now become Twitter.

The question is, what can you do to predispose this kind of thinking and/or kicking things off in the right direction from the beginning? Let’s start from the top…

On starting: Being something for someone, not everything for everyone

Positioning is an oft-ignored concept that gets lumped into ‘general marketing’ and isn’t thought of as a starting point for defining value to your customer as well as your company’s strategy. Positioning, in summary is about thinking how your company sits within the mind of your potential customer and the overall market.

In “The Dip,” Seth Godin talks about how if you cannot be ‘the best’ then you might consider the incremental benefits of persevering down the path you’ve chosen. I propose, for the purposes of early stage startups, that what Seth meant by being ‘the best’ could be restated as “being appropriately and distinctly positioned within the mind or circumstances of your target audience.”

If from the start of your company’s launch, a customer sees value in what you are offering because no one else offers it, then by default, you are the best option.

Thus, ‘bestness’ can be achieved both by either entering a market that already exists and with a new proposition appropriately positioned in a way that ‘bests’ all of your competitor’s offerings, or by create a new market to satisfy the latent needs of customers and creating a new ‘best’ category for yourself.

If from the onset of a new project or business you cannot conceive on how you can either push through the necessary work to be the best in an existing category, or appropriately position your value proposition as a new type of offering to a target customer, you might want to continue refining your ideas until you reach one that has a clear value to a clear group of users who will see you their best option.

Anything short of that, and you start running into differentiation problems against established competitors. As a starting point, on my blog post on the product market fit cycle I talk about how you can integrate the concept of positioning into part of your company’s ongoing analysis.

During: Knowing what you want

Just being the best or differentiated from your competitors isn’t always enough. If you don’t know what you want, how will you know if you’re getting it (or not)?

Having a strong vision of how you want to operate your company and how you want your company culture to develop, matters. It matters in helping align all employees around a cause, around a work ethic, around solving something for someone that they fully understand.

It allows you to make decisions about the tone of your company when speaking to your customers and employees, the quality and nature of your products, and what’s sufficient for you to consider a product experiment succesful.

The best talk on the web about this very topic is Simon Sinek’s TED talk on the subject.

Define what you want and why you want it, anything short of that will lead to you and your team being pulled in many different directions constantly.

On ending: The benefit to quitting at the right time

Let’s say that you’ve hit a plateau in growth or exhausted your ability to find a segment and/or beachhead for your company to target, one potential solution is that you start compromising on your original vision.

Perhaps you wanted to have a certain type of service offering or a specific customer, but by having to address a different segment or customer your personal goals are compromised. For example, let’s say you had a social cause in mind, but the only way you could get your idea to ‘work’ is by moving to a non-social cause. Will your heart be in it?

If this happens, now what?

Time and resources are precious – both in life and in the startup world. By shifting your focus of energy at the right time onto a new project or by altering the one that is not working, you free yourself up for a new victory rather than perpetual stagnation or worse, failure.

So if you’re in a situation with a product, feature, or company where it is clear that persevering could merely create a waste of resources usually in the form of time and money and frustration for all, it might actually be better for you to quit and attempt something new, or ‘pivot’ one aspect of your customer to positioning/product/go2market relationship.

By quitting early, you don’t waste energy going down a path that is inefficient and leading you nowhere and opens the door for new beginnings and new ideas.

Next: If that’s the case, then why don’t more people quit confidently?

Paralysis: But why do we sometimes NOT quit?

So, if there are clear benefits to quitting when it is clear we are going nowhere with an idea or project, what generally stops us from doing so?

Below are some reasons why we don’t budge when we should:

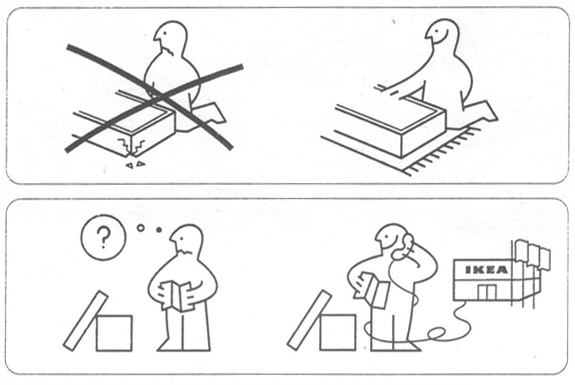

1) We sweat sunk-costs too much (The IKEA Effect)

Quitting or just giving up on something is a big word. It comes with lots of social stigma. We’ve been brought up in the west to ‘never quit’, to persevere at all costs. We are taught by society that quitting is what losers do and isn’t respected.

Unfortunately, this mentality can create a myopic tendency to arguably stick with things way beyond when one should. Those accomplishments or efforts that we sometimes hold on to as barriers to moving on to new things are called sunk costs.

Sunk costs can come in many forms, you might be overly invested to what others may think of you if you quit, what your family might think, etc. You might fall in love with an idea or product too much, or you might have beliefs about commitment, perseverance and not letting anyone down.

A version of sunk costs is the IKEA effect, whereby we value things more if we’ve put in effort.

In the words of Nik Brbora, (a Clipper Round The World sailor and Chief Software Engineer for Seedcamp company Saberr):

The IKEA effect basically says that once you build something yourself you love it a lot more and place disproportionally high value on it. Even if it is not as good.

To you, this value is way higher than to an outsider because you built it. To quit would be to face loss of this (to you) huge value. And that hurts disproportionally more than when compared to the outside market value of that gain.

Having something fail doesn’t necessarily have to be a massive failure, it all depends on how big the attempted experiment was in the first place.

One way to avoid building up too many ‘sunk costs’ is by taking smaller bets. For example, if you were trying out a new business idea, service, or feature, it could be that you ‘quit’ the market segment you are targeting, and you target a new one (the classic ‘pivot’).

In his book titled “Little Bets,” Peter Sims talks about how by not over-committing on massive projects from the start, you can cycle through ideas and innovations far faster and at a lower cost

This concept isn’t new, and any reader of the ‘The Lean Startup” will recognise the concept.However, it’s worth noting that many times we forget to think of ‘little bets’ in all aspects of our attempts, be they marketing, communications, or even a new sport, not just when it comes to product development.

One side benefit, naturally, of accumulating these little bet ‘failures’ is that your experience and ability to adapt will grow stronger and when you do find something that works, you will be that much better at dealing with it.

2) We fall subject to The Loss Aversion & Endowment Effects

The Loss Aversion Effect is what makes us prefer preventing a loss vs potentially gaining a higher gain later. It is one of those irrational quirks that makes us human.

This is why trial periods work: you fall in love with something during the trial period, and then fear the loss more than the gain you would have by passing it up for something potentially better in the future.

This effect is the reason why many hold on to stocks or their failing startup for longer than they should. Other good resources on this include Dan Ariely’s YouTube lecture on the subject and this Psychology Today article on the subject.

The Endowment Effect is proximal to the Loss Aversion Effect and the IKEA effect, but basically its about how we value that which we have far more than what we don’t have. Literally, we think it is worth more than the market pricing would give it just because we own it.

3) We actually don’t really know what we want, so we don’t really know if we are getting it

As I mentioned early, from a strategic point of view, knowing what you want is such an integral part of actually achieving it. This may sound absolutely basic, but it’s very easy to just get carried away with whatever others think and not really mentally commit to what you personally value and set out to do from the start.

This vision you should have isn’t necessarily about having specific clarity on how something plays out, as no one really knows what the future will bring. Rather, it’s about focusing other variables, such as, what kind of company culture you want to have or what type of customers you want, or what kind of products you are passionate about.

You need to start defining what your vision is, otherwise success starts becoming a moving target – and moving targets make it hard to know when you’re failing.

From a more tactical point of view, defining milestones and KPIs for success can help you get a feel for whether a hypothesis you are testing out is met. By defining some milestones up front for your company you can track your expected progress more tightly, rather than constantly letting things slip and not having clarity as to why they may be slipping.

4) We are too busy believing other people’s stories (The Bandwagon Effect)

In the words of Gabriel Hubert from Seedcamp company Nitrogram:

I think some founders don’t quit because they’re still too influenced by perceived “success” or progress of others, etc… Companies are rarely doing as well as they say they are, and founders should beware of attending too many events that only encourage them to listen to these stories.

We are subject to falling victim of the Bandwagon Effect whereby we want to be like others. If other startups say they are “killing it,” you want to believe you are too… even if that’s not entirely true.

Fight your own battles, but know why you are fighting them and when you should reconsider.

5) We are fearful of what will happen and if anything better will come

The last main reason why I believe many are unwilling to quit is because we are afraid about whether anything better will come along after you move past your current project.

The people you are working with, could you build a better team? The idea you have, could you come up with a better one? The money you raised, could you raise again with a failure under your belt?

Ironically, in some recent studies around happiness, it turns out that there are a couple of tendencies that play in your favour. Apparently, how you feel over time, is inherent to your predisposition towards life.

This is called the Set-Point theory of happiness. In other words, if you’re a positive person, if something negative happens, with time you will rationalize it, integrate it into your life, and after some time, your life perception will return to how you were before.

According to the theory, basically, no matter what you fear will happen, your perception of the eventual outcome after a time, will be no different regardless of the positivity or negativity of the outcome, it all depends on how you, as a person, perceive life to start with. If you want to read about this more, another definition for this is the Hedonic Treadmill.

So, if “time neutralizes all wounds,” so to speak, would you be that much more willing to give something a shot?

After a transition: Your recovery network

Networking can help founders develop their company and find the right people and opportunities. However, it also has a hidden benefit: It’s your post-transition safety net.

People that are open to meeting new people and do so on a regular basis are more likely to see identify new opportunities and have the very people they interacted with during their previous journey help them out in recovering.

It is pretty common to have CEOs of companies that have moved on to other things become employees of other startups, or go on an start a new company and recruit people they met in their journey in new endeavor.

One of the things we have seen time and time again in a close knit group of companies such as Seedcamp is that because of the nature of how founders get to know each other, they transition to other startups within their network, effectively providing them a safety blanket of options from being in the same network.

In Conclusion

- Understand what your vision is and what success means to you

- Understand who your target audience is and what being ’the best’ in your category means to you and them

- Take smaller bets, which can fail, but won’t over-compromise you or your resources

- Quit/Pivot when you see the signs of not being able to ‘be the best’ in your selected segment after your time goal has passed

- Acknowledge the emotions that come with quitting, but know that whatever crisis you are going through, it too will pass

- Never stop building a network, this will be your net – keep them posted on progress, ask advice, and notify them if you are moving on. If you’ve been talking to mentors and investors and other startups and given to the community, they will remember you and help you out.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.