“The reader is a friend, not an adversary, not a spectator.” – Jonathan Franzen

Scroll, scrolling, scroll, stop. A slice of content caught the ever-roving eyes of today’s digital consumer amidst an endless timeline. Click the link, fly to the website, and recognition resumes.

Sounds familiar? That fascinating collection of information, the one that caught your eye with its tempting headline and whimsical illustration, is becoming more likely to be placed by a corporation – a company entirely separate from the site on which you’re reading.

This is native advertising in real life, on a real website, acting as a key player in the race for the strongest, viral, engaging content.

Native to what?

Native advertisements attempt to camouflage with their digital environment—websites and apps—with the ultimate goal of monetizing user experience through content that looks, reads, and shares like their established neighbors.

The tactic is to place information with intended value (and a bit of brand name-dropping) in the stream. Native advertising evokes an organic experience – one that pays tribute to the design and UX which has and continues to advance the Web.

Currently, there are some brewing questions for advertisers looking to do it right, publishers attempting to walk the fine line of voice protection, and engaged consumers constantly reading and sharing. If content is—at its conception and execution—an advertisement, does it matter? If that content is valid, honest, and engaging, do advertising dollars alter the message? Or is it in essence just means for advertisers to reach more eyeballs?

Timelined

Native advertising is not new. However, it’s grown considerably in popularity on the digital advertising block.

Eighty-four percent of publishers believe there is a value add for consumers through native advertisements, according to Hexagram’s ‘The State of Native Advertising 2014.”

Ink-stained print media have used native advertisement in the form of advertorials for years. Facebook placed promoted posts in your newsfeed to look like your friends posted it, before you notice the “sponsored” annotation. Twitter did the same thing with mobile-advertising exchange, MoPub, in 2013.

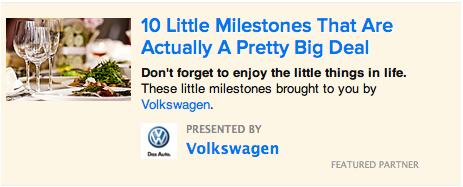

BuzzFeed’s popular listicles are often sponsored content. The company, known for viral social content, is predicted to bring in $100 million in revenue in 2014 from native advertising on 150 million unique visitors a month, according to a 2013 Forbes article.

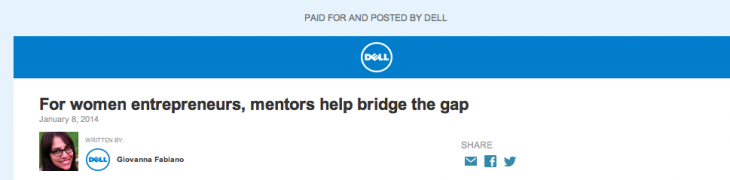

Newspapers with heavy Web presence, such as The New York Times, are in a unique position to move forward with increased sponsored content, (if they choose to do so). When the behemoth for traditional journalism debuted its redesigned Web experience with the inclusion of native advertising by Dell, discussion was reignited.

With 41 percent of brands engaging in some sort of native advertising and 62 percent of publishers offering options to do so, this evolved product has the legs to further change the way we create and interact with advertisements.

Read all about it

The good news is that native advertising is quiet, in all of its various forms. The ad tactic avoids disrupting the consumer experience with loud, low-performing banner ads. Plus, native advertising is seen as a reassuring revenue stream for upstart publishers, with 57 percent of investors say they are likely or very likely to invest in a company that sells native ads, according to Solve Media.

Advertisers have the chance to move away from low-performing traditional digital ads with a maneuver that reaches more eyeballs and encourages engagement. If the consumer appreciates and engages with the native advertisement, value is added for both parties.

Tyson Quick, CEO at Instapage, said he advertises his business through popular and easy to set-up social native ads.

“We’re currently using these ads—sponsored stories or tweets—to grow our network so that we can pull marketers into our brand, extend our reach at a low cost and ultimately generate freemium users,” Quick said.

From a publisher perspective, Demand Media, hosts native ads on its content channels, including Cracked.com. Jean Lin, senior director of public relations, offered up the example Rough Guides, a travel guidebook publisher, ran on the site. The agency’s in-house studio crafted the lead article, “6 Modern Playgrounds to Make Your Modern Child Lose Its Mind.” The piece was surrounded with the advertiser’s branding, splashboxes and a background.

This example brings to light one of the lasting benefits of native advertising in the form of content. Instead of being removed from the newsfeed when the promoted post’s ad spend runs out, the content lives on and creates higher brand value.

For Cody Cheshier, business development manager at Demand Media, it’s all about quality content.

“We don’t buy Web traffic. The content we make is very authentic and the engagement is organic,” Cheshire shared. “We try to play consumer rather than producer.”

Crossing the fine line

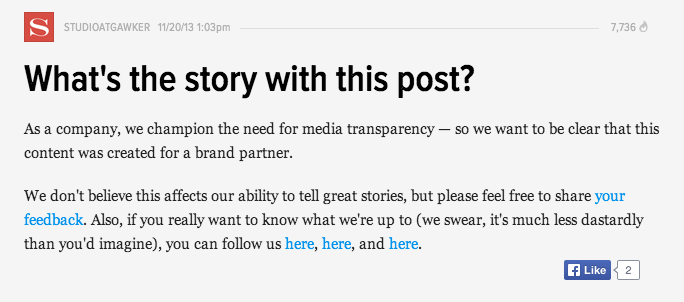

One of the glaring observations of native advertising is the fine line publishers and advertisers walk between deception and complementary content. Publishers should not want to alter the voice of their platform, wavering for a larger piece of the ad dollar pie. Accepting money for content that doesn’t add value, just branded noise, is more nuisance than notable.

Advertisers, in turn, should avoid alienating readers with deceptive content.

So how should one avoid these native ad pitfalls? Vice President of Product Development and Content Strategy at SFGate and the San Francisco Chronicle John Miller offered up some advice.

“The key to all of this is to focus on the reader experience,” Miller said. “If you are truly delivering something of value to the reader, they don’t care where it comes from. If you inform—not sell—you create a relationship with the reader.”

Stewart Marlborough, EVP, media at Demand Media, says that the right advertiser—one whose product is in-line with the environment—makes all the difference.

“If you have the right advertiser with the right frame of mind, native advertising can reach the right people,” Marlborough said. “It fits if what we’re doing for you, the advertiser, is something we would be doing already.”

An ad by any other name

Unlike banner ads with standard specs, native advertisements come in all media formats, including video, interactive graphics and photo streams.

The common ways to mark a native ad as an ad vary from different colored boxes around the content, like The New York Times, to an entire BrandVoice category on Forbes with follow buttons, surrounding banner ads, and company-specific pages within the site. The content has the look, feel and engagement options as other non-sponsored Forbes content.

Unlike the usual unbound question and answer sessions on Reddit, 2013 Gawker Media hosted a Q&A with scientist personality Bill Nye on Gizmodo in the comments section of a “Summer Science Symposium” page category sponsored by State Farm Insurance. From header to comment footer, the entire experience was an ad, but one with value added by an expert, active discussion and information.

Steps are being taken to help differentiate between the good, bad, and ugly native ads. The Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) published the “IAB Native Advertising Playbook” in December as the product of a 100-member task force.

The document classified six types of native ads and recommends guidance for clear transparency is needed for consumers’ trust.

More recently, the UK IAB chapter announced it will form its own working committee on the topic following a survey of members with 52 percent saying they knew what native advertising was, but needed additional information. The move comes as a preliminary defense to set precedents for government regulation, consumer protection and standardized practices.

To the future and beyond

Do not expect native ads to disappear into that locked Don Draper closet of floundered ad formats. Publishers are offering advertisers an increasing number of creative solutions to reaching target audiences, beyond the banner.

Buying the byline is only expected to continue. For native advertising to have its full place at the table, in all of the minds involved, it’s fine unless it falters too far.

“Never before have advertisers been able to connect with customers in such non-obtrusive ways,” Quick closed. “I dare to say, ads might actually start enhancing peoples’ lives…and many probably already are.”

Disclaimer: The Next Web offers native advertising, and clearly marks paid-for content as such at the top of relevant articles.

Top image credit: Shutterstock/bloomua

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.