The leak wasn’t even a screenshot. It was a photo of a BlackBerry with a BBM on the screen. A secure text-messaging network had been compromised by the low-tech screenshot.

Innovative Ventures CEO Mayer Mizrachi’s team was building an app for the Navarro presidential campaign in Panama in 2013 when the security breach occurred. The photo of the phone was leaked by the opposition and Mizrachi realized that BBM (the messaging system that prides itself on being secure) was a security liability. It stored messages on a device that could be compromised by anyone with a cheap point-and-shoot. In response, Mizrachi’s team built a version of the Jigl app that didn’t store any information. Like Snapchat, everything was deleted after few seconds.

The campaign found the app so useful that in October 2013, it was released to the public as HASH. It was marketed as an app for professionals, but teenagers quickly picked up on it too. While the app solved one security issue, the fact that anyone could sign up for an account made it less than secure.

Limiting accounts reduces the chances of a third-party leaking information. The lessons learned during that campaign and the HASH release led to the creation of Criptext.

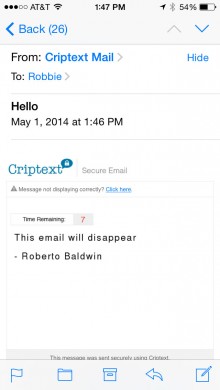

The Criptext app expands the features of HASH and uses five forms of security to reduce the chances of vital information being leaked. Each message is only available for 15 seconds. But, the ephemeral nature of the app extends beyond messages. Criptext messages can also be emailed to users outside a predetermined network. Like the in-app texts, the messages disappear after 15 seconds.

The Criptext app expands the features of HASH and uses five forms of security to reduce the chances of vital information being leaked. Each message is only available for 15 seconds. But, the ephemeral nature of the app extends beyond messages. Criptext messages can also be emailed to users outside a predetermined network. Like the in-app texts, the messages disappear after 15 seconds.

All these messages are encrypted with a mixture of PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) and a proprietary encryption technology. “As opposed to every other messaging app that focuses on very strong encryption. If you break that app’s encryption, you have access to everything. We are adding privacy and limitations,” Mizrachi told The Next Web.

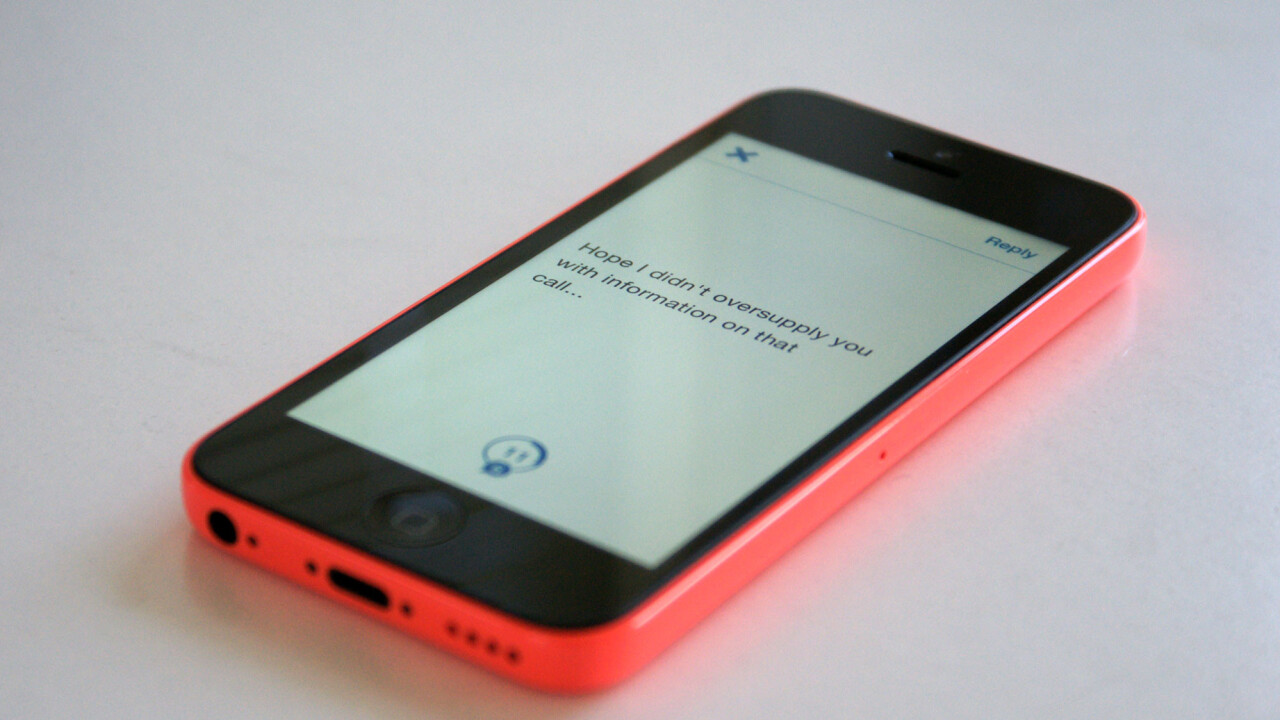

Those limitations include screenshot alerts. But screenshots also end up missing vital information. Messages don’t display the name of the sender. It’s a message without context.

If, for example, Tim Cook were to send you a Criptext message with the details of the next iPhone and you took a screenshot of that message, there would be no indication within that the message was sent by the Apple CEO.

But the service goes even further, all messages are untraceable. Each message is sent with a temporary, unique handshake identifier. If a nefarious individual was to get access to the system, they would be unable to intercept messages and determine who sent and who received the message. Access to the database would be useless as well. Messages are not stored on a server or in the app.

But the service goes even further, all messages are untraceable. Each message is sent with a temporary, unique handshake identifier. If a nefarious individual was to get access to the system, they would be unable to intercept messages and determine who sent and who received the message. Access to the database would be useless as well. Messages are not stored on a server or in the app.

And finally, the one piece of the puzzle that Mizrachi learned while working on that campaign in Panama, control. “We are able to separate work from pleasure by controlling who can use the app and who can not,” says Mizrachi. A company’s IT department is in charge of everything. You have to be invited to the app by your company. The service can be installed on company servers or run from the severs. There is no public option within the app.

Criptext wants to be the new BBM without the dwindling market share. It already has one government using the service in Latin America and several telcos interested in adding Criptext to their network. That’s impressive since the company only just finished developing the technology and hasn’t focused on marketing.

The firm wanted to create a solid system before it started touting its service to the world at large. “A lot of companies launch on promise or credibility. In our case we’re doing a bit of both,” says Mizrachi.

Of course, were still left with the odd name, Criptext. When asked why the name wasn’t Cryptext instead, Mizrachi had a simple answer, “We did not want to pay $28,000 for a domain.” Instead, the company put the money into development.

When creating a service to send secure messages in an increasingly unsecure world, that’s probably the smarter decision.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.