Magical. The word has been used hundreds of times in Apple’s marketing to describe its products, but really took prominence with the introduction of the iPad. When Apple CEO Steve Jobs took the stage in early 2010 to introduce what we all knew at that point to be some sort of new tablet product, one of the first adjectives he used for it was ‘magical’.

Contrary to anecdotal wisdom, the term magical was actually only used 3 times in that iPad introduction, twice by Jobs and once by the iPad’s designer, Jony Ive, in a promo video. Yet the term resonated with people. How could something that was built almost completely on existing technology, was less powerful than almost any new laptop and was essentially a larger version of Apple’s own iPod touch, be magical?

To add to the flames, after the introduction of the iPad the term was suddenly everywhere. We had the Magic Mouse, the Magic Trackpad and a host of commercials sprinkled with a liberal dose of ‘magical’. The word was used as a rallying cry for critics saying that the iPad was nothing new and lampooned by parody commercials and advertising.

Magical success

The iPad is a resounding financial success, with sales in excess of 25 million units so far. By comparison the Motorola Xoom has sold, at best, around 125,000 units and, while 500,000 BlackBerry PlayBooks have been shipped, it’s unclear how many of those have been purchased by consumers. The interesting thing here isn’t the fact that the iPad is successful, it’s the reason why.

By all practical counts, the iPad should have made a medium-sized splash and settled into a slowly climbing slog towards the next generation device and the next after that. The specifications are relatively unimpressive, the processor is a dual-core 1 GHz chip, which is actually slightly worse than what the Xoom is packing. The Xoom even has more ram, a larger, higher-resolution screen and a better camera.

Instead, it managed to duplicate the hockey-stick shaped adoption curve of the iPhone and launch itself into prominence as the only truly successful modern tablet computer on the market.

Now, it’s clear that the iPad isn’t actually magical by the dictionary definition. It doesn’t fly or spontaneously generate fairy dust that cures all ills. Yet the adjective is used extensively in Apple’s descriptions and it makes a lot of people angry to see Apple ascribing such a distinctive descriptor to a product that they consider to be evolutionary at best. But most of those people are much more technologically savvy than the average iPad user.

To people that are familiar with the physical parts of the iPad and the OS that it runs, the iPad may seem like nothing but a combination of hardware and software that has existed prior, tucked into in a stylish new package. This is actually a valid viewpoint because that’s exactly what it is. There is definitely nothing magical to be found in the raw components that make up the iPad.

But the magic of the iPad isn’t the hardware, or the basic features of the software, which we have seen for years in the iPhone. Instead, it exists in the way that users interact with it.

Breaking down the magic

The magical nature of the iPad lies in the intuitive grasp of its operation by almost anyone who touches it. It’s in the way that it does simple things very quickly. The way that, using the full screen, it transforms itself into hundreds of different tools at the tap of a finger.

Apple understands several fundamental things about the way that people’s minds work and the way that they interact with technology, including the iPad.

Human beings interact with our world through touch. The keyboard, the mouse and other input devices that we have used to input commands into computers act as an intermediary that turns a keypress or click into a command. The iPad uses touch as directly as possible to allow users to interact with it, removing as much of the translation barrier as possible.

Other tablets, like the Xoom and PlayBook, also use this method. But, at least at this point, none of them have refined the responsiveness of the touchscreen to the point where it ‘sticks to your finger’. We all know how things should react when we touch them, immediately. When something doesn’t, it’s incredibly evident to anyone, whether they’re tech savvy or not. When a person who doesn’t understand the technology behind it, or doesn’t care, touches the iPad’s screen and things respond instantly, it feels magical.

People want their lives to be less complicated, not more. In addition to showing that Apple has an intense grasp of the way that people interact with their world, the iPad’s design also shows an understanding that our lives are densely packed with information and stimuli, so when we use a new piece of technology that’s so intuitive it doesn’t even require an instruction manual, it’s an almost physical relief.

The iPad advertisements that use the word magical do so in the context of complex tasks that the iPad can help you to accomplish easily. By contrast, Verizon’s tablet commercials miss this concept completely, choosing to stress that ‘your wife will love the dual-core Tegra 2 chipset.’ No she won’t. Even if she’s familiar with Nvidia’s chipset lineup, she most likely doesn’t care. Most people just want to have and use things that work well, without the burden of weeks of learning curve and they aren’t impressed by specs.

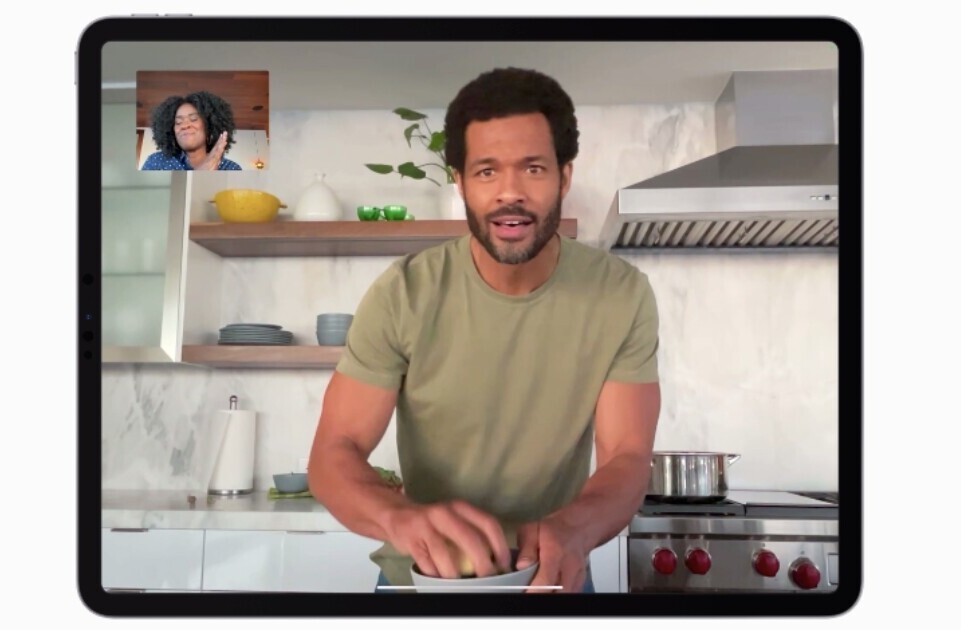

Life doesn’t happen in a vacuum. I’ll freely admit that even Apple’s commercials tend to be unrealistic about when and how most of use use the company’s products. We don’t use them sitting comfortably in a spacious living room or a brightly lit morning kitchen. In reality, when we’re checking our iPhone or poking at our iPad there are screaming kids, traffic, smelly passengers, crowded trains and tons of other stimuli all vying for our attention. The magic of the iPhone and iPad is that they can be used in situations where there is a lot going on and still be easy to use. They require a very small portion of our attention and concentration to operate.

Apple’s attention to detail in interface design makes using the devices feel almost transparent, this allows us to devote much more of that concentration to the content being displayed on the screen or the world around us. Getting a device to the point that it feels like a natural extension of our hands is incredibly difficult and it’s something that Apple excels at.

Only a small portion of Apple’s customer base wants ‘more options’. There are several million jailbroken iPhone users, but those millions are nothing when compared to the 200 million iOS devices on the market. Not to mention that the main reason that a lot of those people jailbreak their phones is the ability to unlock them. As the iPhone becomes available at more carriers, a lot of that will go away.

This is also the reason that Apple uses the word magical and not a list of specifications to describe its products. There is little magic to be found in a list of hardware, but much to be found in the enticing simplicity and power of a device that can do so much with so little effort. This lack of customization does tend to alienate ‘power users’ that thrive on customization and tweaking, but it hasn’t hurt Apple’s business in the rest of the market, which is far larger.

The future of magic

While the impact of the iPad has been felt on the market with its incredible financial success, we’ve only begun to see the effects of the iPad on the future of portable computing. A look at the smartphone market pre and post 2007 easily demonstrates the impact of the iPhone on the way that Apple’s competitors design and market their devices. The tablet market was caught even more flatfooted than the mobile space and now, a year and a half after the introduction of the iPad, we’re only now starting to see market challengers emerge.

None of those has gained any real traction yet, and it’s hard to say which of them will be first. Perhaps the HP touchpad will make a splash with its relatively well-recieved WebOS software and HP hardware. At some point another manufacturer will stop seeing the iPad’s magic as a marketing adjective and more as a way of thinking about user interaction. Until then, well, we’ve always got the iPad 3.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.