Humans have a weird relationship with robots, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. We’re simultaneously delighted and appalled by their capabilities and autonomy. When we see what the latest inventions can do to make our lives easier, we immediately hear a voice in the back of our mind: “Great, but how long before it betrays us all?”

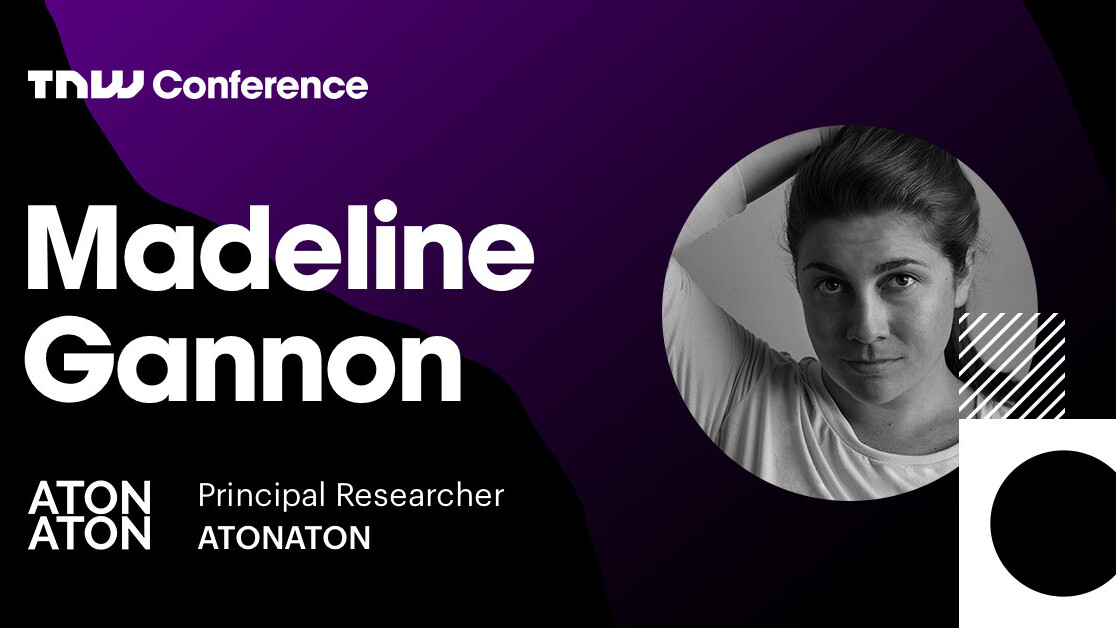

Having those concerns is normal, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Madeline Gannon, known as the ‘robot tamer,’ is a designer who explores our relationships with robots. Through her research studio, ATONATON, she programs machines to interact with humans through animal-like behaviour – creating more organic movements that put us at ease. Ahead of her keynote at TNW Conference next week, we asked Gannon about her work, the future she envisions, and how robots will become a larger part of our lives.

You’ve previously mentioned that you “fell into” the world of robotics. How did this happen? Is it easy to enter this field without a certain degree?

Yes, I’m a roboticist by practice, but not necessarily by formal training. I’ve managed to find myself in spaces where there have been big machines just sitting in the corner, all lonely, with nothing to do. Industrial robots, in particular, can be programmed to move and do simple things just using 3D modeling software; and with my background in architecture, I was very comfortable with those tools. That’s how I started learning how to talk to robots.

But as soon as you want to ask these machines to do more complex or atypical things, you really need to know how to speak their language. And for me, that process of learning how to program and learning different machines languages was certainly less comfortable. Over time, I was able to gain technical proficiency, and I began translating between the often divergent worlds of design and robotics.

How has your background in architecture influenced your work in robotics?

One gift of an architecture education is a hyper-sensitivity to how people move through space. And once I figured out how to talk to robots, I was able to give my machines these same sensibilities. But this particular knowledge has only recently become relevant to robotics. For a long time, research has focused on, ‘Can we get a robot to move from Point A to Point B?’ Now we know the answer — yes. So as these machines come out of the lab and into the wild, we need to develop more thoughtful and inclusive ways to co-exist with one another.

What is the goal of ATONATON? How has your work broken down boundaries between robots and humans?

One of my goals for ATONATON is to show that if robots are going to live in our cities, streets, sidewalks, and skies, then they need to be more than useful. They need to be meaningful. We fill our lives with a variety of meaningful relationships: from pets that give us unconditional attention and enthusiasm, to trainers who give us physical strength and abilities, to teachers who give us knowledge and mastery. Robots, with their super-human strength, super-human speed, and super-human attention spans, have the potential to fit into these relationship models, and help us become better versions of ourselves.

We still seem to have a lot of unanswered questions about how we can use artificial intelligence and robots ethically. How can we begin to overcome those hurdles?

One of the biggest challenges is the lack of collective imagination for what our futures with intelligent, autonomous machines should be. We know the future we don’t want — we don’t want AI and robots to enslave us or replace us. But as a society, we haven’t decided the futures we do want with these machines. We need more voices contributing their own perspectives to bring a breadth of new options and alternatives.

What project will you be working on next?

There’s sort of a logical progression in my robotics installations; I’ve gone from an installation with one person interacting with one robot, to many people with one robot, to many people with many robots. The next step is many robots interacting with many robots. There is an entire ecology of intelligent machines that are joining us in the built environment, and I’m curious about the relationships that will emerge between these different species of machines.

When do you think it will be common for robots to interact with us and enter our homes on a daily basis? What will these interactions look like, and how is your work looking to influence it?

In many cases, that future is now. Go into a modern hospital, and you can find autonomous robots delivering medicine and supplies to a patient’s room; in supermarkets, you can find robots scanning and wandering aisles to update inventories; in homes, you can find robot vacuums cleaning (and mapping) your floors; in cities — like Pittsburgh, where I’m based — you can find multiple driverless car companies testing their systems on public streets. These are not the humanoid-looking robots that we were promised in science fiction. But then again, they bring unique abilities that go beyond the limitations of the human body.

Want to learn more about Gannon’s work? Catch her speak on stage at TNW Conference on May 9 and 10 in Amsterdam. Don’t have your ticket yet? Get yours now.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.