TNW Answers is a live Q&A platform where we invite interesting people in tech who are much smarter than us to answer questions from TNW readers and editors for an hour.

Yesterday, Nick Montfort, a computational poet and an award-winning author of interactive fiction, hosted a TNW Answers session. During the AMA, Montfort spoke about what computer-generated literature does better than humans, the future of computer-assisted journalism, and how computer-generated novels help enlarge cultural imagination and explore new possibilities of language.

At first thought, computer-generated poetry may seem like a new and unexplored area of literature. So, what exactly is it? Well, as Montfort said: “That’s a simple but amazingly difficult question.”

An example of what computer-generated literature can be is one of Montfort’s tools that was developed to find hidden poetry from any web page. The Deletionist removes text from articles to discover a network of poems called ‘the Worl’ within the World Wide Web.

[Read: This tool erases web page text to reveal hidden poetry]

Does computer-generated literature outdo human potential?

When people think about AI and advanced technology, the main worry usually stems from if — and when — it will one day take away all meaning from human existence, along with our jobs. And this fear rings true for writers and journalists too. At TNW, we have a robot writer that, on more than one occasion, has performed better than us human writers.

“There are indeed writers who worry that computers will take their jobs,” Montfort said. “To me, the most interesting computer-generated literature is that which is very non-human, and yet still manages to speak to us and resonate with us. This sort of literature is hardly going to threaten a person’s job, unless that person has made their living trying to imitate robot writers.”

So, I guess we’re safe… for now. But what about the future of computer-assisted or generated journalism?

“Computers can be very good at “textualizing” data – weather data, seismological data, Little League baseball games,” Montfort explained. “So if you have some underlying data that can be rendered in textual, narrative format in a straightforward way, why not have the computer do it through a process of generation?”

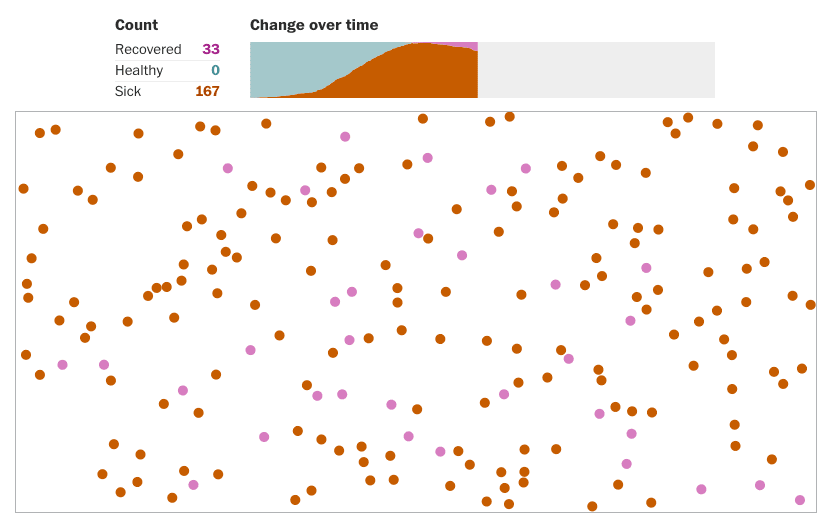

“Other types of computer assistance are very different. There was a great Washington Post article recently which had live computer simulations of disease, under different scenarios, embedded in it. It made the case that social distancing was even more effective than a forced quarantine for preventing the spread of disease. And let me note, this wasn’t a data visualization. It was actually a pure computational simulation, or model, in support of this argument. So what is sometimes called “data journalism,” but really goes beyond that to computational journalism, is another great direction.”

Computers will beat you at Scrabble every time

There are arguably thousands of jobs and everyday tasks that have become almost effortless thanks to the advancement and harnessing of technology, specifically AI. However, Montfort is sure that, for now at least, technology doesn’t compare to human intelligence and creativity. Computers are actually very constrained creatively. What makes them interesting is that their constraints are very different compared to human constraints.

“Computers are tireless in mining data, producing combinations, and working towards objective functions. They can be extraordinarily dogged and compelling explorers of language. And of course, they can fill out formal patterns. They will beat you at Scrabble every time,” Montfort said. “But – here I’m leaning on something journalist Italo Calvino said in the 1960s, which remains true – they don’t have individual and cultural histories. So, right now, while a computer can help us see things in data, it’s hard for a text to actually mean something deep to a computer. At this point, we have to tune what they do and supply the ‘ghost in the machine’ to take advantage of their otherwise amazing capabilities.”

Adding the “Arts” to STEM

Undeniably, computational literature isn’t an area of interest for everyone, which Montfort believes “unfortunately can be said about a lot of compelling literature and art.” To give this field the interest it deserves, Montfort advises, “Expanding STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) to STEAM (adding the Arts) is one great idea. That helps us see the arts as a valuable way of providing perspectives, provocations, and explorations that can complement what happens in science and engineering.”

Want to get started in computational literature? You can read Montfort’s poems here, and he’s also provided an extensive list of what to read by MIT Press during your time quarantining.

You can read the whole of Nick Montfort’s TNW Answers session here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.