A promotion from Uber offering drivers the chance to earn a 33 percent earnings boost in exchange for an upfront payment of $115 is causing controversy, and has lead some to accuse the controversial ridesharing company of charging drivers to work.

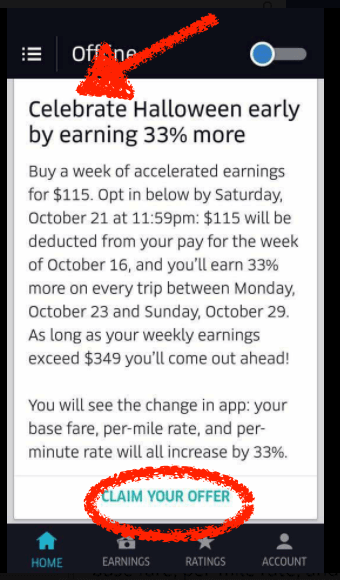

One damning critique, from NYC-based technology ethnographer Alex Rosenblat, argues that the format of the offer is deceptive, as the headline (“Celebrate Halloween early by earning 33% more”) is larger and bolder than the rest of the copy, which clarifies that this is at the expense of $115 from the previous week’s earnings. She also mentions that the format of the promotion is similar to other Uber driver promotions, where drivers don’t have to pay in order to take part.

Uber states that if drivers earn more than $349 in a week, they’ll ultimately come out on top and make a profit. Given that Halloween is party season, and people are more likely to leave their cars at home in order to go drink, this doesn’t seem like a particularly insurmountable number. Indeed, an Uber representative I spoke to described it as “one of the busiest nights of the year.”

But obviously, there’s an element of risk involved. There’s no iron-clad guarantee that they’ll make that money back. What if their car breaks down at the start of the week, or business is unpredictably slow, either due to some inclement weather, or a saturation of available drivers, all chasing the extra bonus?

Before we get hyped up, it’s worth clarifying a few points about the promotion.

- It’s only taking place in a handful of markets.

- It’s not permanent.

- The experiment is an undertaking between Uber and two researchers at MIT. According to an Uber representative, the study looks at “the value of flexibility, specifically the flexibility that the Uber app offers by comparing it to taxi-like lease models where you pay an upfront ‘fee’ rather than as a function of the work you do”

- It’s opt-in. There’s no obligation to take part, at all.

- Drivers are informed that they’re taking part in an experiment, via the terms and conditions.

- Uber has been pretty transparent. You can actually read the research paper associated with this experiment here. It costs $5, and I just got a copy for free, as the National Bureau of Economic Research offers free access to the press. That said, it’s a pretty dense piece of academic writing, and I haven’t been able to fully digest it yet. If there’s anything particularly interesting in it, I’ll update this post.

- The experiment had to receive approval from MIT’s Institutional Review Board.

I’m not sure I agree with Rosenblat’s argument that the promotion is deceptive. The only way you could be deceived is if you merely read the headline, and then pressed “okay.” The copy is plainly written, straightforward, and is explicit about the nature of the agreement. The very first sentence reads “Buy a week of accelerated earnings for $115.” The only thing that isn’t immediately clear is that drivers are taking part in an experiment.

As a regular reader of the /r/uberdrivers subreddit, I agree that the format of the promotion matches closely the design previous Uber promos. Is that because Uber is deliberately attempting to muddy the waters, or because Uber has a distinct branding and design language that it uses across the entirety of its digital real estate? Personally speaking, I’m inclined to think the latter.

Rosenblat, quite reasonably, makes the case that there’s something very troubling about the idea of an company experimenting with someone’s income. In his post, she argues:

“When Uber leverages its ongoing employment relationship with its drivers to experiment with their livelihoods for academic research purposes, it also raises a few questions and concerns regarding Uber’s power over these research subjects.”

I spoke to her over Twitter, where she clarified further what she meant by this:

“There’s a vast information and power asymmetry between Uber and its drivers, and promoting certain pay schema where Uber controls dispatch for the rides you will receive, comparative promotions, and your eligibility to work makes this less of a straight forward employment auction, and more of a gamble.”

This element of a gamble doesn’t sit easy with Rosenblat, who correctly pointed out that circumstances can emerge that rob people of not only the chance to make the bonus, but also the $115 upfront fee. “If you’re ill that week, or something renders you unavailable, you lose the down payment to afford flexibility. It strikes me as an odd exercise to induce drivers to sign up for shifts that contract the rhetorical terms of the job.”

Rosenblat acknowledges that Uber is no stranger to experimenting (or indeed, adjusting) the terms and price of its service. This is just a continuation of that trend, and may prove beneficial for certain drivers. “Uber and others, including its competitors, experiment with pay incentives all the time,” she said. “And it may well be that having a variety of options for work contract configurations benefits the diverse motivations drivers have to do this job.”

That, I think, is the most salient point of all. Uber’s workforce of drivers is as diverse as it is massive, and judging by the significant attrition rates, the current one-size-fits-all model isn’t working. Perhaps this academic research is a necessary evil in order to ensure that the company is able to serve not only seasoned full-time veterans, but also casual drivers, who take to the streets as part of their side-hustle, in order to earn a bit extra money.

I reached out to Uber for comment on this story. A spokesperson said: “Drivers tell us that they value the ability to choose when, where and how long to work. This academic study is part of broader efforts to better understand the extent to which drivers benefit from Uber’s flexible work model in quantitative terms.”

It’s worth reminding ourselves that this is just a small experiment, taking place over a short period of time in just a couple of the markets that Uber serves. But I do worry about the implications about what happens if this experiment is successful, because it could see Uber pursue a more aggressive gambling element to its business model. That’s not always going to work out for the driver.

The problem with gambling is that the house always wins. Always. And in this instance, Uber is the house.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.