Comet Atlas is racing toward the inner solar system, and it could become the brightest comet seen in the night sky in over two decades. The comet, discovered by an observatory designed to protect Earth from asteroids, may even be visible during the day just two months from now.

Also known as C/2019 Y4, this comet was discovered by astronomers at the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) in Hawaii in December 2019. At the time, the comet was exceedingly dim — but the comet became 4,000 times brighter in just a month. This increase is far greater than astronomers predicted, and could potentially signal the comet may soon be exceptionally bright.

“Comet ATLAS continues to brighten much faster than expected. Some predictions for its peak brightness now border on the absurd,” stated Karl Battams of the Naval Research Lab.

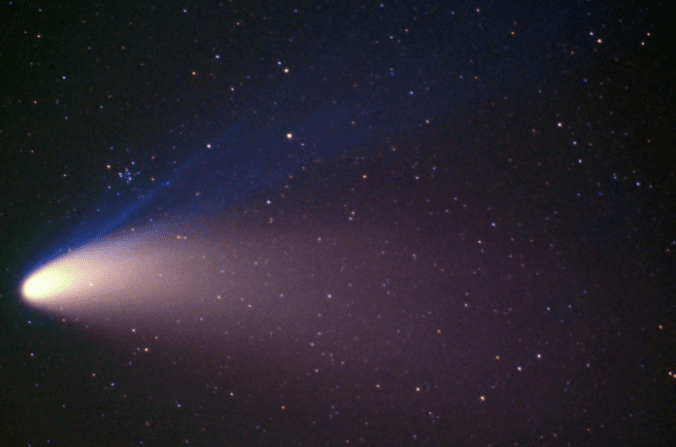

Comets are, essentially, dirty snowballs. As the comet approaches the Sun, the heat will drive off some of the ice which makes up the nucleus (main body) of the object. If the comet holds it shape as it continues to heat, then Comet Atlas could grow as bright as the planet Venus (the brightest object in the night sky other than the Moon).

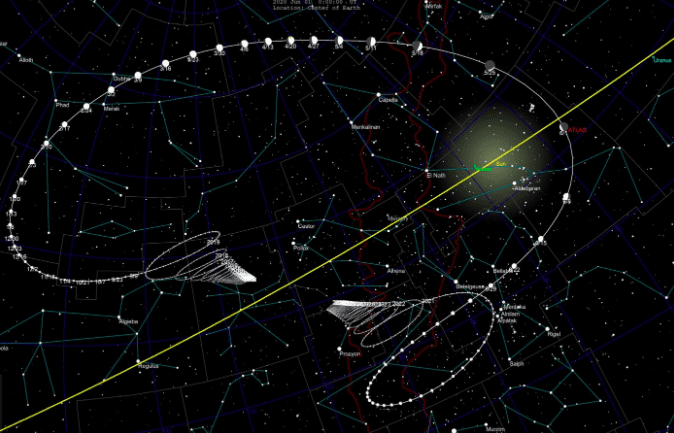

The comet, currently near the orbit of Mars, is closely following the path taken by one of the great comets in history — the Great Comet of 1844.

At its current rate of brightening, Comet Atlas could be visible to the naked eye, under dark skies, during the first weeks of April. For skywatchers in the northern hemisphere, this would be a sight unseen since the dual shows of Comets Hyakutake in 1996 and Hale-Bopp the following year. When Hyakutake was at its peak, the tail of the comet stretched halfway across the sky.

In May, the comet could shine with a green hue, providing a unique view for viewers in the northern hemisphere.The brightest predictions for the comet suggest it could become bright enough to be seen during the day.

The peak brightness of Comet Atlas would depend, largely, on how much material is encased within its nucleus. If the comet is sizable, and it does not fall apart as it is heated by the Sun, it could put on an amazing show in May.

The discovery is going to snowball

The ATLAS observatory which first spotted the comet consists of a pair of 0.5-meter (19″) telescopes, placed 160 kilometers (100 miles) apart. The system, operating since 2017, is designed to detect near-Earth objects — asteroids and other bodies which could potentially impact Earth. In addition to finding roughly 100 space rocks measuring 30 meters (100 feet) in diameter or larger every year, the observatory also occasionally discovers comets.

When it was first spotted on December 28, the comet was 439 million kilometers (273 million miles) from the Sun. At its closest approach, Comet Atlas will come within 37.8 million kilometers (23.5 million miles) of our parent star. The comet is brightening at nearly an unprecedented rate and by March 17, the comet was already 600 times brighter than predicted.

The comet is currently in the constellation of Ursa Major (which includes the Big Dipper) and it will remain visible all night (as seen from the northern hemisphere) all night during it pass through the inner solar system.

Several comets astronomers thought were destined for greatness failed to achieve their potential. In 2013, Comet PANSTARRS became as bright as Sirius (the brightest star in the sky), but it was positioned low on the horizon as seen from the northern hemisphere, making it difficult to see. The last two bright comets — McNaught in 2007 and Lovejoy in 2011 — were only visible from the southern hemisphere.

The path traveled by Comet Atlas — the same as that take by the Great Comet of 1844 — suggests that each of these bodies (and potentially others) may have broken off of an ancient mega-comet long ago. The Great Comet of 1844 was first seen by observers at the Cape of Good Hope on December 18 of that year, and was visible without the aid of a telescope through January 1845.

“During the latter part of December and the first week in January, it was a brilliant objects in the southern hemisphere, equaling, it is said, in brightness the celebrated comet of Halley in its last appearance,” The Astronomical Journal reported in 1850.

Out to sea, the calm lagoon waters were darkening, while the comets overhead glowed brighter, omens in the gloaming. ― Julian May, Perseus Spur

Comets are one of the most beautiful sights to see in the night sky, and they make perfect targets for families to view together, creating a lifetime of memories.

Of course, the behavior of comets is notoriously difficult to predict, and some comets once thought to be destined for greatness fizzled.

In 1974, many astronomers believed Comet Kohoutek would light up the night sky, but it failed to deliver. Similar expectations were dashed by Comets Austin in 1990 and ISON in 2013.

If this comet fails to live up to its potential, it will be a long time before we see it again — once it heads out to the outer solar system, it will not return for another 6,000 years.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, an astronomy journalist, fan of coffee, sci-fi, movies, and creativity. Maynard has been writing about space since he was 10, but he’s “still not Carl Sagan.” The Cosmic Companion’s mailing list/podcast. You can read this original piece here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.