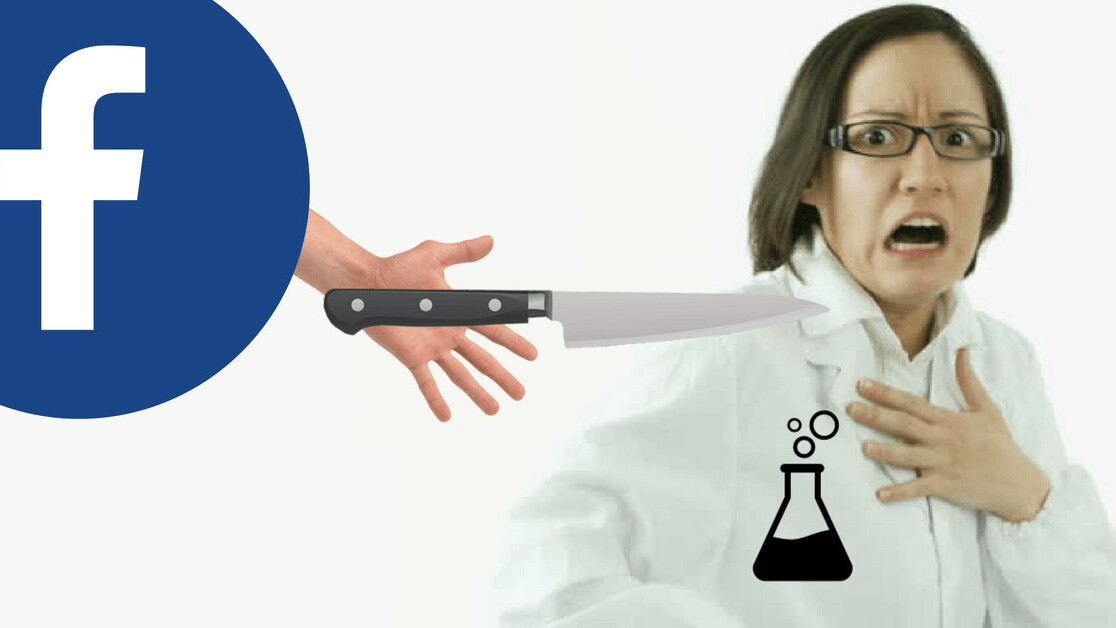

Facebook is closing its doors to researchers in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal. The latest casualty is the app Netvizz, a research tool used by hundreds of academics to gather public Facebook data, that the social network has recently banned.

The app has gathered more than 300 academic citations and has been used to produce studies on everything from Norwegian political party videos, to public opinion about the London 2012 Olympic Games, to Asian American student conferences. But now this fruitful source of data has been shut down.

More significantly, Facebook’s action sounds a death knell for civic access to public Facebook data. Inevitably, all apps like Netvizz will be wiped from the platform.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal, which saw Facebook user data gathered supposedly for academic purposes but instead used by a private firm for political campaigning, created an opportunity for positive change. But Facebook sadly appears to be making its platform more opaque, unknown and unaccountable to the public.

Once apps like Netvizz are gone, there will be no accessible way of gathering large amounts of public page Facebook data. Facebook offers only highly restrictive search options for normal users.

It has started new initiatives to offer access to its data for scholarly research, but these are dependent on a “hand-picked” group of scholars who “define the research agenda”. Without broader access for other researchers, the social, academic and political consequences are dark.

Netvizz offers users the ability to extract basic data from public Facebook pages, such as the content and frequency of posts, likes, shares and comments.

This can be used to analyze what users are discussing, how they feel about certain things, or how they respond to certain content. And this can feed into studies on a huge range of important topics, such as how fake news spreads or how social media can affect young people’s mental health.

Netvizz is an internal app within Facebook that uses the social network’s Graph API (application programming interface), a piece of software that provides access to data. Netvizz then organizes this data into a spreadsheet format that can be easily read by anyone.

Importantly, it doesn’t gather personal data on users. But Facebook’s API is becoming a closed system, meaning that this basic public data is becoming impossible to access, threatening our knowledge of the world.

Without access to user data in this way, it will be a lot harder to spot patterns in what users are doing and saying on Facebook.

In response, Netvizz’s creator, Bernhard Rieder of the University of Amsterdam, said: “academic research is set to be funneled into new institutional forms that offer (Facebook) more control than API-based data access.” He added: “independent research of a 2+ billion user platform just got a lot harder.”

This isn’t just a headache for thousands of academics worldwide. Given the growing influence Facebook has over political debate and behavioural trends, it means that the public could be denied important information that is vital to protecting democracy, social relationships and even public health.

For example, my own research into British political parties’ campaigns on Facebook is set to become much more difficult. Without apps like Netvizz offering a gateway to extract public political content, messages sent to voters during elections will be too discrete to investigate.

In this way, society’s capacity to question what political parties are doing is being curtailed by Facebook, undermining democratic accountability and our power to understand politics on social media.

The questionable use of Facebook data by academic researchers and political campaigners in the Cambridge Analytica scandal highlights the need for new privacy and security measures.

But Facebook has already successfully altered API access over the last few years, preventing further personal data from being gathered in the manner of Cambridge Analytica, while allowing research with public data to continue.

Facebook had struck the perfect balance between privacy and access. But the company now appears to be building a wall around its data, not to just to protect users but also to protect itself.

And in doing so, Facebook is also protecting the powerful, curtailing our ability to scrutinize and question the influence of politicians, corporations and others with the money to spend on large advertising campaigns. By prioritizing privacy over transparency, Facebook is setting up a potential ban on this knowledge.

A legal framework is needed to guarantee Facebook users and researchers at least some access to API data for public pages, especially for those of national interest such as political parties, media organizations and government bodies.

Facebook must go further than its current restrictive plans and open its data to help promote research and democratic accountability.

Several petitions have been started, including one I have launched, to encourage Facebook to do this. But a bigger “#openfacebook” campaign is needed that could work in conjunction with similar campaigns to make targeted advertising more transparent.

It’s still possible for Facebook to rethink its data policy in a way that respects individual privacy and limits the potential for data misuse, but also promotes transparency, accountability and independent research.

If Facebook does not alter course, it will catastrophically undermine our ability not only to understand the social network machine and its millions of pages, but also the entire political and social order that the internet has created.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Tristan Hotham, PhD Researcher, University of Bath. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.