MacPlaymate started as a joke, one that Mike Saenz told 30 years ago at a friend’s birthday party in New York City. A joke that appeared as a pixelated woman named Maxine in the confines of an Apple Macintosh. It was funny and everyone loved it, but that joke would become the most complicated relationship in Saenz’s life.

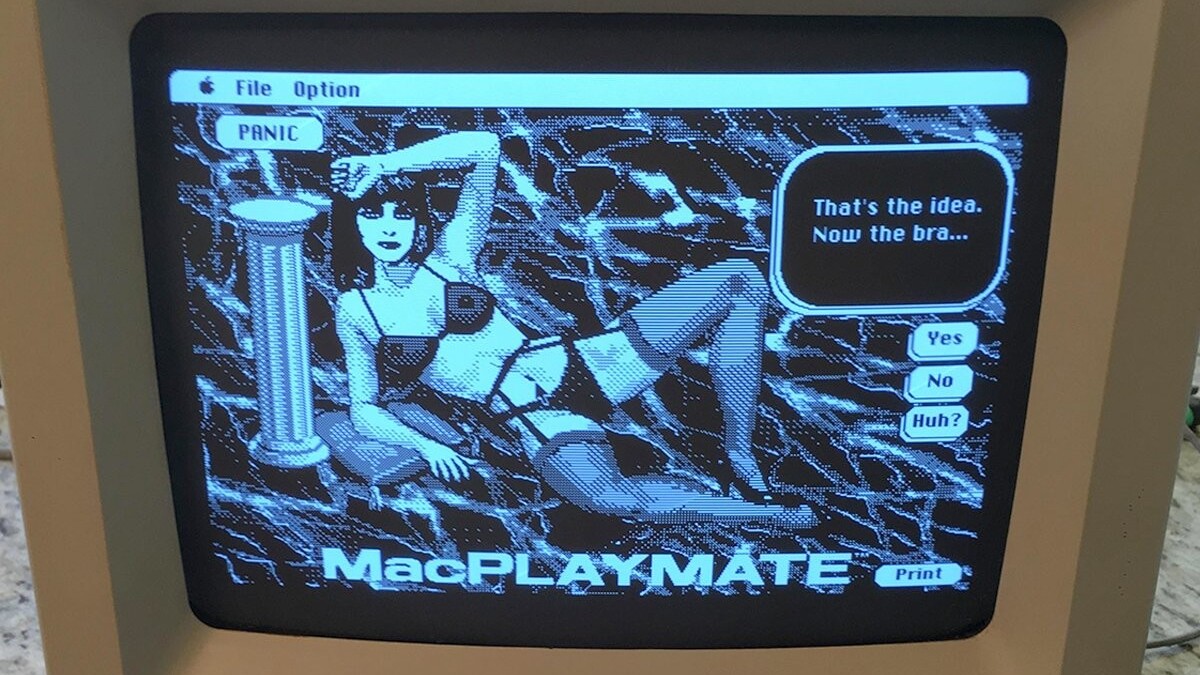

In MacPlaymate you would take Maxine’s clothes off, because the goal of MacPlaymate — if you could call it a goal — was a to pleasure Maxine with sex toys like the “Mighty Mo Throbber,” “Deep Plunger” or “Anal Explorer.”

You could dress Maxine in stockings, a bondage outfit or “a full fetish ensemble” while commanding her to masturbate in one of six different ways — complete with moaning sounds, of course. You could also add a female sex partner named Lola. Another feature of the game was an innovative “Panic” button that hid gameplay behind a spreadsheet. You know, for the NSFW crowd.

Before it came 1982’s Custer’s Revenge for Atari — where you, playing General George Armstrong Custer, tried to rape a naked Native American woman tied to a pole. Then in 1983 came Stroker for the Commodore 64, which involved 8-bit penises and the ability to masturbate them. In 1986, MacPlaymate took the Apple Macintosh’s simple black-and white-palette and turned it into a pornography playground.

Some might assume only a truly depraved person could create something like MacPlaymate, but as Saenz explains from his home in Sarasota, Fla., over Skype, that was not the case.

“I don’t look back at my childhood and go, ‘How did that affect me and turn me into this son of a bitch who made MacPlaymate?’”

Like any prepubescent boy, Saenz would peruse his grandfather’s Playboy magazines—though as a child he was mostly into fireworks, burning model cars and melting plastic Army men. He also fell in love with Creepy and Eerie, two horror comic book series first published in 1964 and 1966, respectively.

Saenz enrolled at the prestigious Lane Technical College Prep High School to study art, and by the time he was 18, he was working for Marvel Comics and Warren Publishing. Saenz spent two years grinding away at Marvel’s Epic Illustrated anthology, but eventually he needed to make more money. He painted on the side and took on freelance illustrations, like record sleeves for Chicago punk bands The Effigies and Naked Raygun.

One night, a TV news segment on digital art caught his attention.

“Rather than go to an art supply store to buy all these supplies, all I would have to do is pay one bill, the electrical bill, and have a digital paint box,” Saenz says, remembering how he first learned about computers.

On Jan. 24, 1984, Apple released the Macintosh. Luckily for Saenz, one of the first to get their hands on one was a stock trader who had bought some of his art in the past.

He would spend the next year illustrating Shatter — a two-tone science fiction comic book series co-created with Peter Gillis, and the first comic to be wholly created using a computer program (MacPaint, to be specific). It sold 100,000 copies in three days, breaking the existing independent comic book record.

But it was only when Saenz fiddled with a beta version of MacroMind’s Videoworks Interactive on the Apple Macintosh 512 that he started testing the limits of the program by creating something inspired by the issues of Playboy he’d seen as a kid — a crude, experimental game.

“What kind of animation can I do with such a limited computer?” Saenz asked himself. “Limited memory, limited size on the floppy disc. What kind of game can I build that’s repetitive yet still holds your interest?”

The answer: “interactive erotica.”

He would call it MacPlaymate, and he spent two weeks programming the game. “It was the first time someone had programmed something where you could click on the woman’s blouse and then it pops off,” Saenz says. “It reminded me on the cheap novelties in the novelty stores — peep-show keychains.”

One of the many folks enamored with MacPlaymate was Frank Brooks, a banker from Connecticut. He wanted to sell the game. Saenz was into it, first cleaning up MacPlaymate’s code and then whipping up a simple package for it. This was all done in preparation for MacWorld, an Apple-dedicated trade show founded in San Francisco, where Brooks intended to sell the game at a booth Bates had already rented to show off his typeset software, JustText.

In January 1987, Saenz, Brooks and Bates traveled to California with a stack of MacPlaymate floppy discs. The trio wore suits. A cardboard box ended up being their cash register. “We had a constant crowd of at least 10 people deep,” Saenz says.

MacPlaymate sold for $50, and there were no copies left by the end of the first day of MacWorld, so the trio used a Macintosh machine to churn out new disks. In total, they made $60,000. They were thrilled.

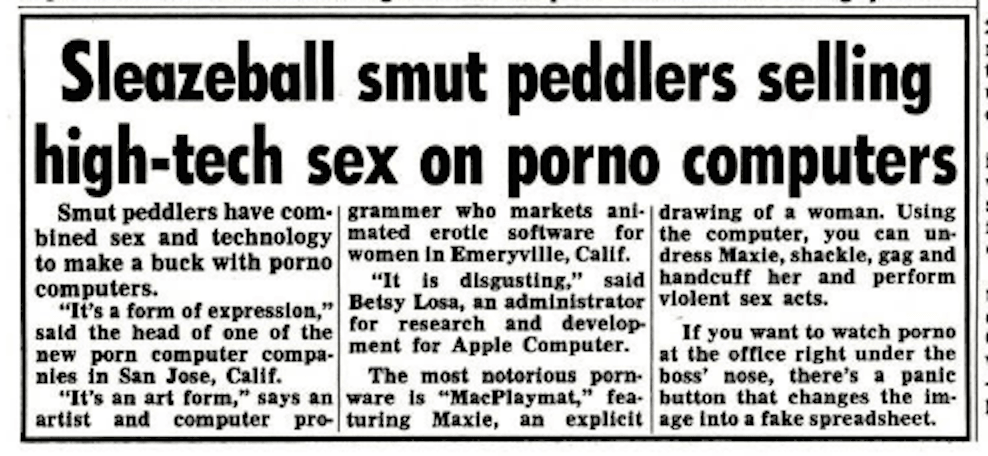

The first company to come after MacPlaymate was MacroMind, which had developed the software Saenz had used “without MacroMind’s knowledge or consent” to create the game, reported Los Angeles Times columnist and public broadcaster Patt Morrison.

MacroMind spokeswoman Brenda Ketter called MacPlaymate a form of exploitation, although Saenz believes that the company was not actually upset at the game, but wanted to distance itself to avoid any potential drama. Saenz was never officially sued by MacroMind.

“The idea that something like this would be considered a game was repugnant then and is repugnant now,” says Morrison today. “Especially in this age where we talk about, ‘What is consent? What does yes mean? Do people take no seriously?’ Here you have this pliant figure, not human, that essentially does your bidding.”

In the Times, Morrison cites an unnamed advertising executive calling the game “MacRape.” But Saenz argues that the game was not exploitative or abusive, adding that he programmed MacPlaymate in a way that prevented the user from abusing Maxine. For example, if the player answered prompts from her fishing for compliments with a negative response, the game — or, in some cases of intense abuse, the entire Macintosh — would shut down.

“It doesn’t remotely get to rape,” Saenz says. “There’s no violence toward her. She won’t even tolerate a mild insult, so how does it even get to tolerating rape?”

Not long after, Playboy sent several cease-and-desist letters to Brooks. Saenz advised him to change the name and packaging, so Brooks took scissors and cut off the “e” at the of MacPlaymate on the vinyl package, creating the less catchy “MacPlaymat.” Nothing else (including the name of the game itself when it loaded on the Macintosh) changed.

Playboy wasn’t amused. In February of 1989, Playboy sued Brooks (and his company, Pegasus Productions) for using the company’s trademark in the title of the game, claiming, “the game hurts its image because buyers may think it was originated or sponsored by the company, which also markets videos, clothing, toys and other products under the ‘Playmate’ trademark.”

Brooks and Playboy settled out of court in an undisclosed agreement.

But it didn’t really matter. At that point, MacPlaymate (as well as the one without the “e”) had become one of the most stolen games in early computer history: It is “probably the most pirated program’’ on the Macintosh, Frank Brooks, president of a Connecticut computer company, told the Times. He also called it “a parody on pornography,” showing designers and programmers just what a computer could do. To some, it was as impressive as it was graphic.

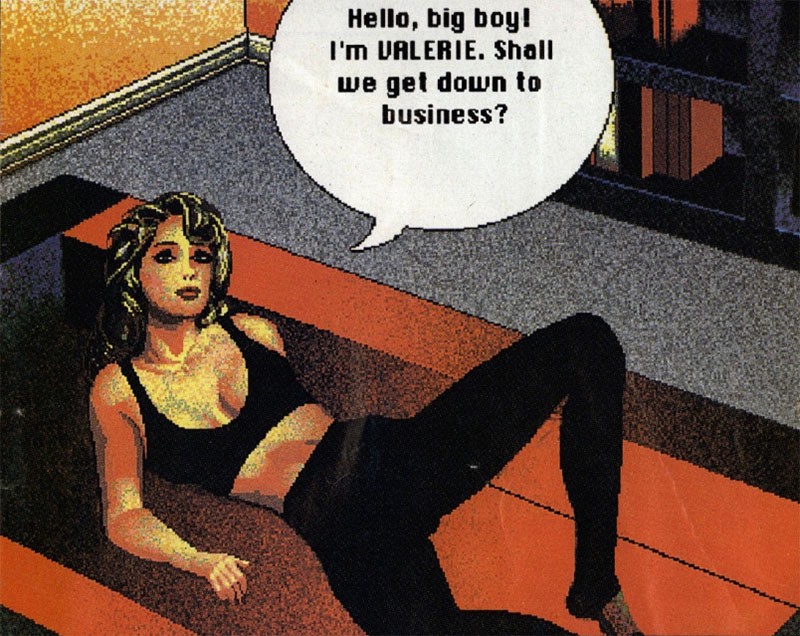

In April 1990, Saenz turned MacPlaymate into a color version on CD-ROM called Virtual Valerie under his new company, Reactor, calling the game “a sexual date on a disk” and charging $99. “An intuitive point-and-click interface makes Virtual Valerie VIRTUALLY YOURS to play with. She’s your cybernetic fantasy and YOU control the action!” read the game’s publicity material. As with Maxine, you had to answer the questions the “right way” to get Valerie’s clothes off, but other than that, most of the structure was similar. The dildos were also “more beefed up and realistic,” Saenz says.

The success of MacPlaymate, Virtual Valerie, Virtual Valerie 2 and the subsequent Virtual Valerie Director’s Cut ultimately inspired porn giant Penthouse — and even Playboy — to invest in their own interactive erotica. For Penthouse, it was Penthouse Interactive Virtual Photo Shoot, where the user acted as photographer, choosing poses, camera angles and special effects. Saenz would publish non-erotic games like Spaceship Warlock, but (to no one’s surprise) none of his Reactor titles made a splash quite like the ones involving naked women. Reactor folded in 2000 because Saenz “got bored” and wanted to get back to fine art.

Saenz has spent the past 16 years painting, sculpting and doing freelance web design work. He has none of the original floppy discs or packagings for MacPlaymate, having lost them during various moves around the country.

But the game had a second wind this past July, when a sales engineer named Huxley Dunsany found a copy of it on a Macintosh SE he bought on Craigslist and photos he took of the game ended up on Reddit.

“[O]nce I spotted the ‘America Online’ folder and MacPlaymate buried inside, all the X10 stuff [a protocol for controlling an entire home from a single computer] sorta fell away,” Dunsany writes over email.

But Dunsany was floored by attention his discovery received. And Saenz was equally surprised. In this day and age of prolific pornography, he never imagined anyone would care about his janky, pixelated masturbating protagonist.

So how did Maxine hold up over the past 30 years?

“My wife was also very entertained by the whole experience,” Dunsany says. “She laughed her head off when Maxine got cranky after we provided not-so-flattering feedback.”

This story is republished from MEL Magazine, a new men’s digital magazine that understands that there’s no playbook for how to be a guy. Sign up for their newsletter here and follow them down here:

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.