More than three billion years ago, Mars was home to vast oceans, and a new study shows this world may have once looked familiar — especially to the residents of Iceland.

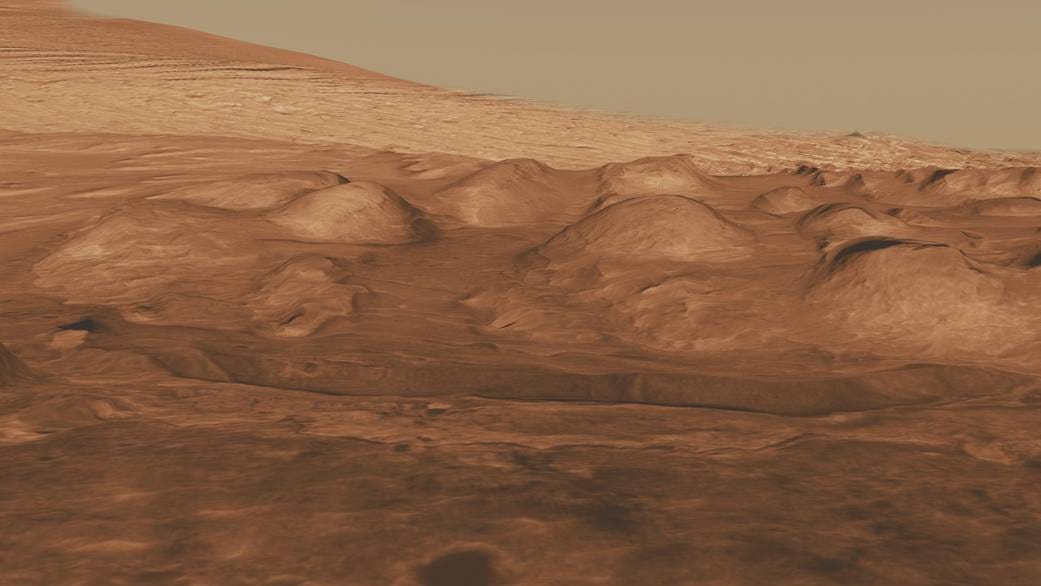

The Curiosity rover has been exploring Gale Crater on Mars since 2012. That region may have resembled modern Iceland, careful examination of the geology of Gale Crater reveals.

Curiosity has been examining mudstones for more than eight years. However, that analysis can not reveal climatic conditions upstream from the sample, where the sediment was produced.

“Ancient rivers and streams on Mars physically and chemically altered the surface, then transported and deposited sediments, resulting in sedimentary rock production in downstream basins, as we observe in the remnants of Gale crater,” researchers describe in a paper published in JGR Planets.

Stroll around Gale until you feel at home…

To get around this issue, Rice University researchers set out to examine data from Curiosity, comparing geological features there to those found in various locales on our homeworld, including Iceland, Idaho, Hawaii, and Antarctica.

[Read: ]

“Earth provided an excellent laboratory for us in this study, where we could use a range of locations to see the effects of different climate variables on weathering, and the average annual temperature had the strongest effect for the types of rocks in Gale Crater. The range of climates on Earth allowed us to calibrate our thermometer for measuring the temperature on ancient Mars,” explains Kirsten Siebach, a member of the Curiosity team who will be controlling Curiosity on the Martian surface.

Conditions in Iceland, featuring high concentrations of basalt, and temperatures averaging just three degrees Celsius (38 F) were found to be the closest modern equivalent of the ancient Martian climate.

Gale Crater is known to have once held water. But, planetary scientists have questioned whether Martian water was largely liquid, or predominantly found in the form of ice and snow.

“Sedimentary rocks in Gale Crater instead detail a climate that likely falls in between these two scenarios. The ancient climate was likely frigid but also appears to have supported liquid water in lakes for extended periods of time,” explains Michael Thorpe of Rice University.

Weathering the stone

The temperature was found to be the most important condition affecting the weatherization of sedimentary rocks formed within streams. And, the effects of weathering were extremely light in the Martian rock. In some ways, these three-billion-year-old rocks were similar to those found along a typical stream in Iceland today.

Typically, geologists examining mud within rocks would expect to see a more highly-soluble deposit quickly washed away from mud (compared to the rock) due to the small average particle size within the mud.

However, this study found little loss of these minerals within mud deposits, suggesting they were formed at fairly low temperatures.

The team was also able to piece together clues about climatic changes on Mars, showing the Red Planet had climatic periods ranging from those similar to those seen in the Antarctic, to conditions resembling Iceland.

Techniques utilized in this study could also help us understand the geology of Jezero Crater, following the arrival of the Perseverance rover (with the first helicopter ever designed to fly on another planet) there on February 18.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.