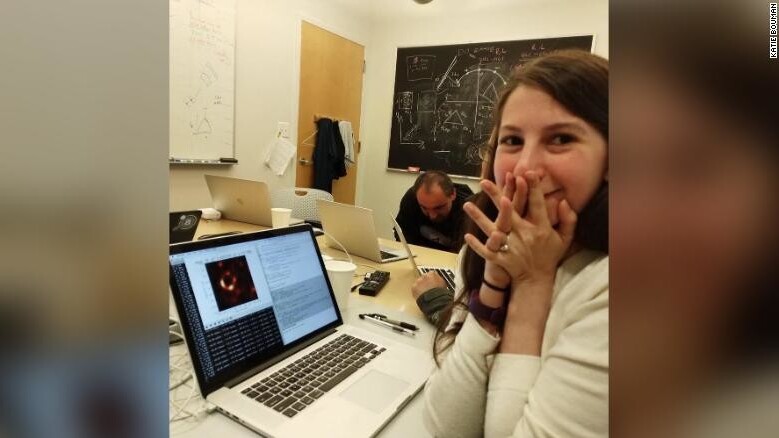

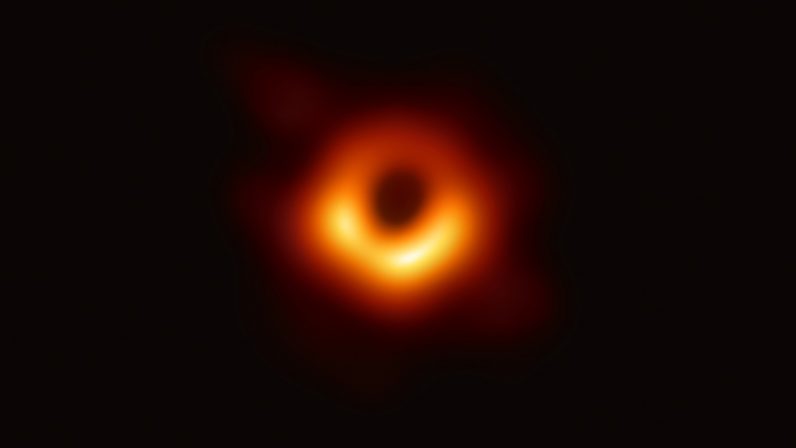

Astronomers today published the first ever images of a celestial phenomenon we’ve long known to exist, but were unable to capture: a black hole. And it’s thanks, in large part, to the algorithms created by Katie Bouman.

Bouman, a graduate student at Harvard, worked with a team of three fellow researchers to create and develop the algorithms that made the image possible. Together, the team utilized enough image data to fill thousands of hard drives, seamlessly stitching together photos from eight telescopes — located in Hawaii, Chile, Mexico, Spain, Arizona, and the Antarctic — to create the image released today.

The data collected from these eight linked telescopes, collectively known as the Event Horizon Telescope, had to be collected on hundreds of hard drives and flown in to a central processing center; there was too much of it to send over the internet.

That’s where Bouman and her team went to work. Last June, once the data finally arrived, Bouman’s team essentially hit the go button, anxiously awaiting the answer to a question the scientific community has had for years: “could we produce an image of a massive black hole?”

“We all watched as the images appeared on our computers,” Bouman told Time. “The ring came so easily. It was unbelievable.”

When she joined the team six years ago, Bouman didn’t know a thing about black holes. Her background was in computer science and electrical engineering. But that didn’t deter her from “coming up with ways to see or measure things that are invisible,” she said. In fact, it made her well-suited to this particular project, one that involved capturing an image of an object so powerful that nothing could escape — not even the light needed for a photograph.

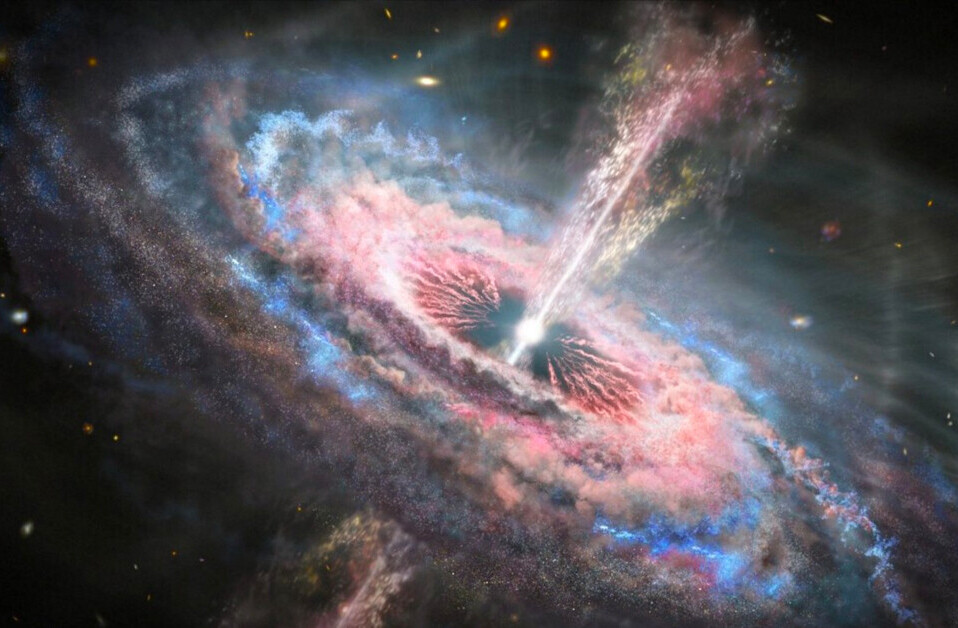

For the team, it’s not just an attempt to photograph the invisible, but a project in which the sheer scale of the object they’re photographing brings with it a whole new set of challenges.

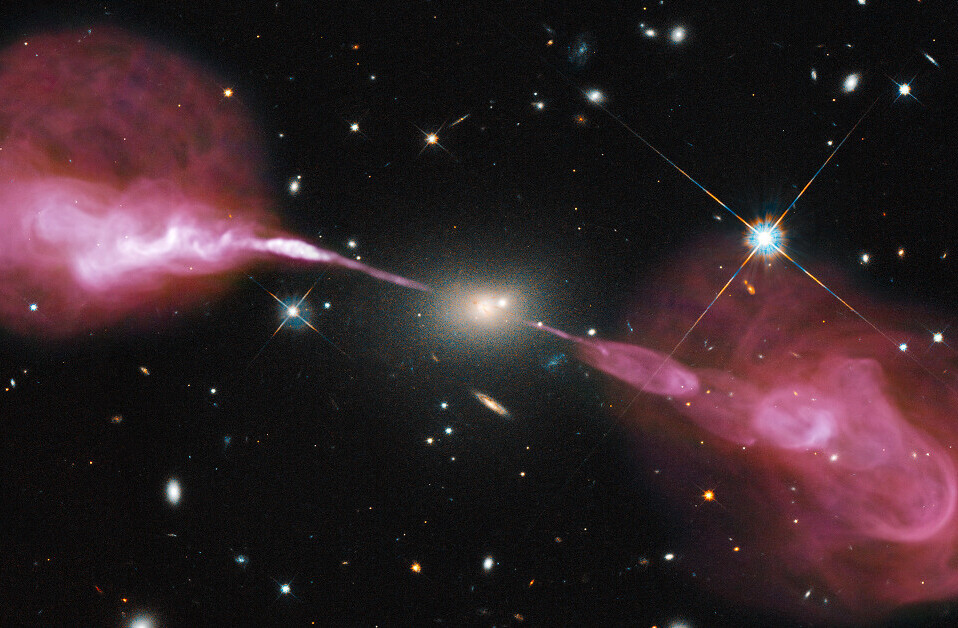

The black hole, found in a galaxy called M87, is larger than the size of our entire solar system, measuring 40 billion kilometers across — three million times the size of the Earth.

If that’s not challenging enough, the black hole is more than 500 million trillion kilometers away. “This is the equivalent of being able to read the date on a quarter in Los Angeles, standing here in Washingon D.C.,” said Shep Doeleman, a Harvard University senior research fellow and director of the Event Horizon Telescope project.

But the team was up to the task. Last June, they sat in a cramped room at Harvard University, anxiously awaiting the answer to the question years in the making: “could they produce an image of this massive black hole?” And as the world saw today, the answer was a resounding “yes.” “It’s incredibly exciting,” she told the Boston Globe. “The goal was to see this thing that was essentially impossible to see.”

Up next for Bouman is a new job. She starts this fall as an assistant professor at California Institute of Technology (Caltech). She also plans to continue working on the Event Horizon team, which is adding satellites, to the network of telescopes already in use. With the extra imaging muscle, she says, they may one day be able to create videos of black holes in addition to the still images.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.