When I was doing research for my very first camera, the Fujifilm X100F, I didn’t know much about the differences between crop (also known as APS-C) and full-frame cameras. I mean, I got the gist of it — but only hypothetically.

You’ve probably heard of the upsides of full-frame sensors already: crisper images even at higher exposure, wider field of view, better performance in low-light settings, higher dynamic range, shallower depth of field, and more defined separation of subject from its background.

In practice, though, none of this meant anything to me. I couldn’t tell the difference between crop-sensor images and full-frame ones. There was one difference I could clearly spot: The price tag. Full-frame cameras were way out of my comfort zone, financially speaking, which in the end pushed me towards APS-C.

In hindsight, that was the right choice. It sure felt this way at the time. Until I started getting gear envy.

One of the more satisfying aspects of buying a camera is learning how to actually use it to capture moments as you see them — not simply as they are. The distinction is awfully subtle, but it ultimately separates an average snap from a powerful image. There are no rules to what makes a great photo, but you know when you’ve seen one. It’s like an imprint on your brain.

It’s a characteristic tough to put into words, but fairly easy to highlight visually.

Go to any stock photography platform, and search for “twins.” I bet you’ll find at least a dozen decently lit, conventionally framed photos of twins, clearly captured by a decent camera. It’s the type of snap you can imagine a person using as their profile pic. It’s a good photo of that person, but that’s all it is — a forgettable Facebook avatar.

Now compare those images to Diane Arbus’ renowned Identical Twins.

They say beauty is in the eye of the beholder, but there is something immediately captivating about this shot that’s absent in twin stock photos. It talks to me as a spectator. It’s not just a photo of twins, but an intimate portrayal of two fundamentally different individuals.

The secret is in the details. The use of monochrome highlights difference, while the identical attire underscores sameness. This tension between difference and sameness is yet again mirrored in the facial expressions of the twins — a frown juxtaposed against a smile. Identical people, different individuals.

Those familiar with Diane Arbus know that concepts of identity, sameness, and difference occupy a central position in her vision as a photographer, but what makes Identical Twins stand out is that you don’t need to be acquainted with her body of work to see that. The photo instantly communicates that vision, it puts those concepts into your mind.

That’s the mark of a great photo, and the ability to produce great photos over and over again is the mark of a skilled photographer.

Unfortunately, that’s not how bad photographers (with inflated egos and insufficient self-awareness) think. We correctly identify great photography and incorrectly attribute “better cameras” to what makes it great. Because it’s easier to accept what separates you from greatness is a couple of thousand dollars — and not talent (or a couple of thousand hours of blood, sweat, and tears to cultivate it).

This brings me back to gear envy.

I briefly lost interest in my photography last year. None of the shots I was taking pleased me aesthetically or conceptually any more, and older images I used to love suddenly repulsed me. I was stuck in a vicious circle where I would constantly seek new places to photograph, but always end up with the same image.

I interpreted what was clearly a symptom of a creative crisis as a sign that I might need a camera upgrade, something mightier and more capable than my puny X100F.

I would search for photographers whose work I adore, and convince myself “I could take that same photo… if I had a Leica M-10P (or another exorbitantly priced camera).”

All of a sudden I had become obsessed with full-frame cameras. I was convinced that shallower depth of field, sharper images, and better low-light performance were the missing ingredients in my photography.

Around the same time, Sony announced the A7R IV — a 61-megapixel beast of a full-frame camera that promises to deliver pure pixel perfection, in video and stills.

I reached out to Sony and after a couple of months of unsuccessful attempts, and I eventually managed to secure a loaner for December. Sony was also kind enough to provide me with a couple of lenses, including the Planar T* FE 50mm F1.4 ZA.

I wasted no time scratching my itch for shallow depthof field, and opened the aperture all the way to F/1.4 right away. I got so fixated with the idea that I hardly bothered to shoot with smaller aperture settings.

The reviewer in me knew this was wrong, but the experience felt therapeutic to the photographer in me. For the first time in months, I genuinely got a kick out of shooting out in the streets. It brought back the unbridled enthusiasm I experienced when I first got into photography two years ago.

I wasn’t simply in love with the process, I was in love with the camera. It fit so nicely in my hands, the feeling was so familiar. I’ve previously spoken about the importance of trusting your camera, and there’s little to doubt about the A7R IV. Everything Sony boasts about — immaculate image quality, snappy performance, and effortless handing — is true.

The A7R IV is so good it makes it difficult to take bad pictures.

It restored my confidence as a photographer. But more importantly, it helped me understand that, while it’s certainly aesthetically pleasing, shallow depth of field comes with its own drawbacks.

One of the biggest challenges of street photography is how fast everything moves. Sony has done an excellent job with its eye detection auto-focus system, but I personally prefer shooting manual — I find it easier to frame images, and it helps me avoid locking in on the wrong subject (which is a problem when there are multiple people in your field of view).

A shallower depth of field leaves less room for error as far as focusing goes. A few centimeters could mean a few more stops’ worth of blur for your subject. That’s not to say you should never use a wide aperture out on the streets, but simply that it might be making the process unnecessarily difficult at times. I got to learn that first-hand.

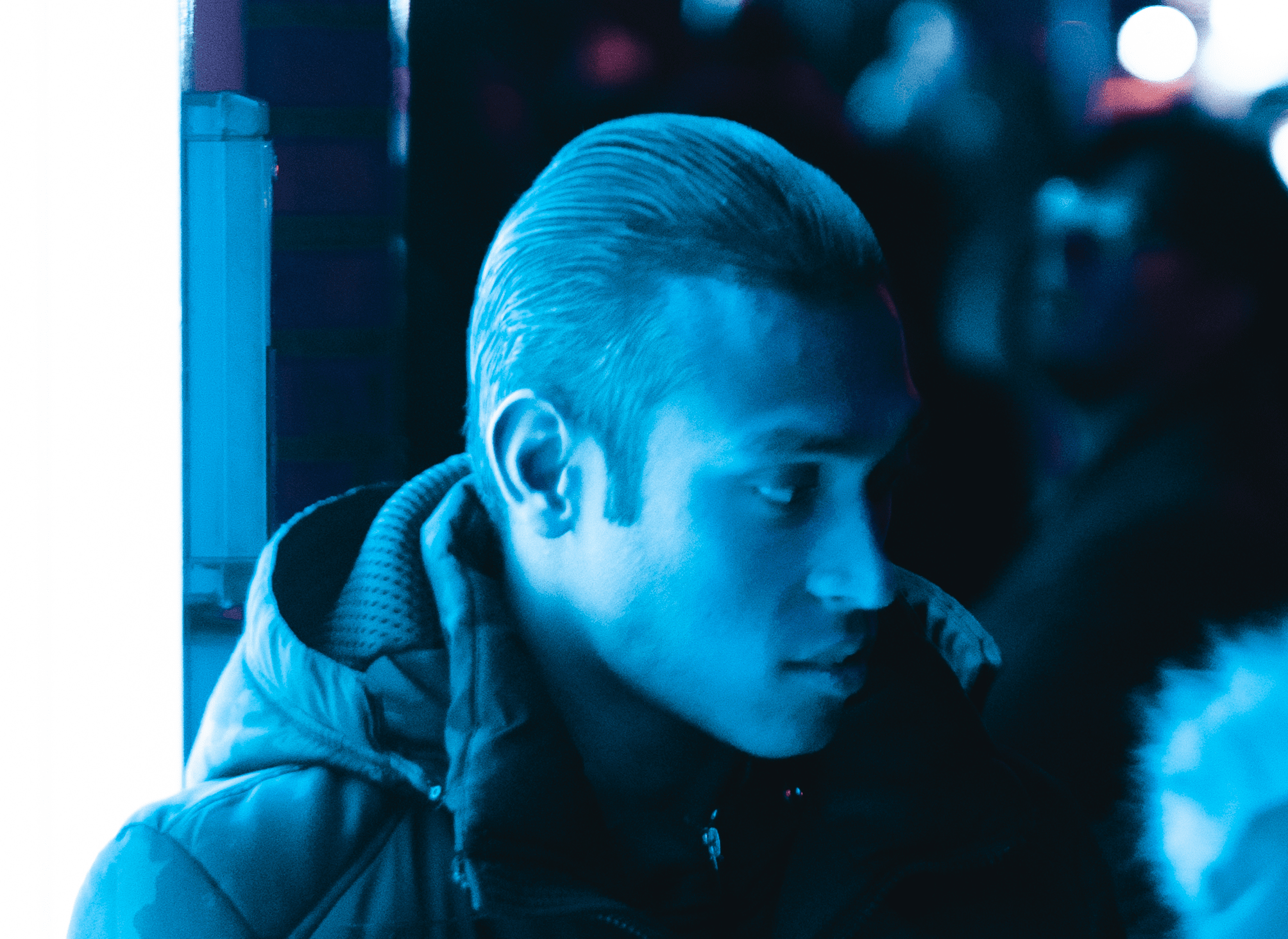

Here’s an image I captured with the A7R IV:

I spotted this light nearby one of my go-to restaurants in Amsterdam, and I waited a few minutes for the right person to step into the frame. I took a couple of snaps, but ultimately settled on this one. I like the intensity in the subject’s eyes, a detail that was missing in the other snaps I caught at this spot.

But if you zoom in, you’ll notice the focus is slightly off — not enough to ruin the image, thankfully, but these minor imperfections will be a lot more noticeable in print.

That’s not a shortcoming of the camera, but an inappropriate technical choice on my part. In fact, shots from the A7R IV are ridiculously sharp even at large aperture, if you nail the focus.

Look at that:

After a few outings, my thirst for shallow depth of field started to wear off. The image quality, as impressive as it is, was starting to make less of an impression on me. Instead, I gradually eased back into my shooting routine — searching for aesthetically pleasing scenes, picking the right moment, and seeking the right angles to snap a shot.

The thrill of flashy new tech is always ephemeral. It vanishes as soon as we get accustomed to it. Then we relapse back into our routines.

This is the most important lesson the A7R IV taught me. Yes, there are undeniable advantages to full-frame sensors, but those won’t make you a better photographer.

Stripped down to their essence, the defining features of the shots I got with the A7R IV aren’t a shallow depth of field and less noise at higher exposure: It’s the way I compose my images, the way I do colorwork in post-production, and the moments I choose to press the shutter button.

I’ve always sought to exhibit moments of solitude and despair in my photography. Sometimes I find these moments in the subtlety of facial expressions, other times I rely on colors and atmosphere to convey this mood.

Take this picture, for instance:

Casinos have always drawn my attention. For a place designed to be a hub of entertainment, there’s something inherently melancholic about them. Anyone who has frequented one of those facilities will know there’s a tiny fraction of regulars who you never see turn a profit — because they don’t.

With the odds stacked against them, there are no happy endings for these people. Only a bitter walk of shame. This story isn’t unique to a specific person, it’s a tragedy playing out at the casino every day. In my eyes, the casino regular is a faceless individual, let down by their own vices and impulsivity.

Red has always conjured associations with danger and vice in my mind, which is what drew my attention to this scene. What was missing was the bitter facelessness of a casino regular, and a shallow depth of field seemed like the appropriate creative choice in this particular situation.

I waited for the right person to step into the frame, and I pressed the shutter. I took the shot with the A7R IV, but at this point this is simply a formality — I could’ve used any other relatively recent consumer camera.

There’s no denying it: The A7R IV is a powerhouse of a camera. It literally does it all. But that comes at a hefty price, $3,499 to be precise. Then you’ve got to budget in a lens (or a few), and Sony glass doesn’t come cheap (even though you can probably find decent third-party alternatives for a bit less).

If photography is your profession, and the studio is your primary shooting terrain — the A7R IV could be a welcome addition to your arsenal, especially if your clients demand technical perfection. The same goes for any photographer whose work often appears in print.

That’s not me, though. Photography is still mostly a hobby for me. And I’ve already got a camera that I’ve built an intimate bond with, a weapon that I trust at all times. As much as I’m grateful to the A7R IV for pulling me out of a creative rut, it’s not the right tool for me.

I’m sorry, A7R IV: I like you, but it’s not you — it’s me.

P.S.: All images in this piece have been snapped with the A7R IV. They’re all heavily edited (and some heavily manipulated). If you’re interested in a closer look at my creative process, follow me on Instagram.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.