There’s a new member in our editorial team: Satoshi Nakaboto. Usually I get along great with my colleagues, we joke, we share our Monday blues, and braid each other’s hair — but Satoshi is… different. He’s a bot.

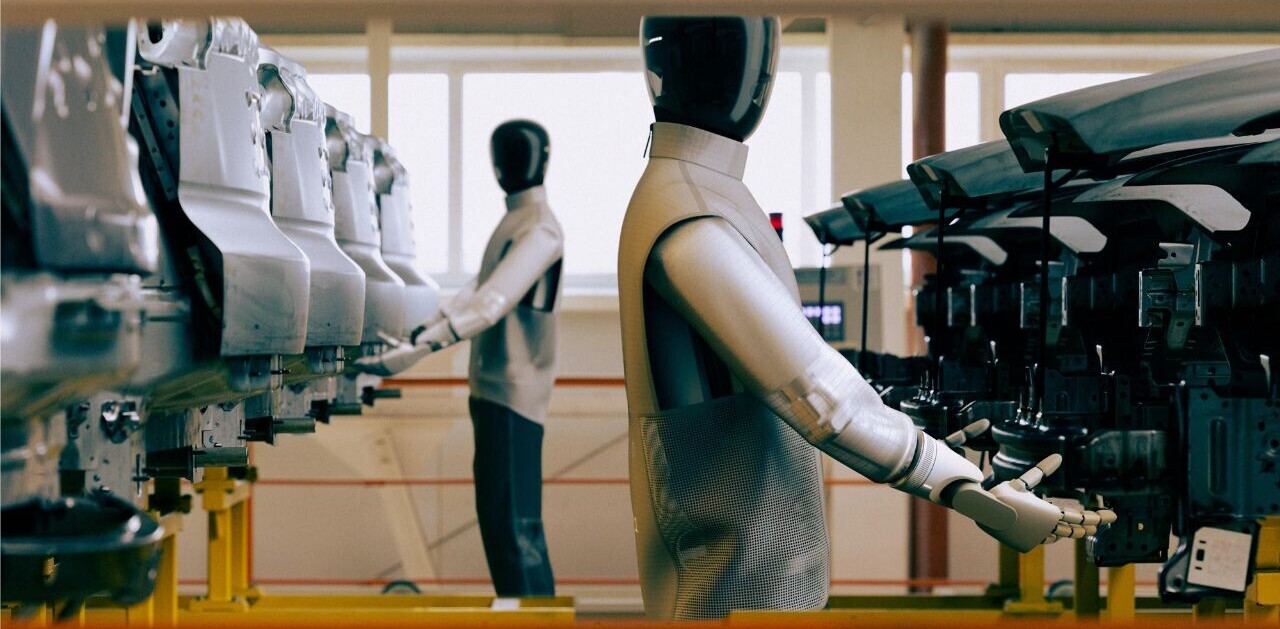

Amazingly futuristic? Absolutely. We’ve gone beyond just talking about when robots enter the workforce, and actually made it happen. We wrote a script which scours the internet for news about Bitcoin; how its price is developing, what people are tweeting/writing about it, and then it puts together all that info in human understandable terms — derived from rule-based phrases and terms we wrote beforehand.

So, what did I think of this at first? I honestly thought it was a smart move. As a tech reporter I’m of course aware of the fact that AI isn’t a threat to the workforce, and its future is collaborative. Also, robots aren’t that good at writing, so I don’t need to worry about my own job. Satoshi does the mundane stuff, which leaves us human writers more time to write something fun. The perfect example of the symbiotic relationship between man and machine.

Or so I thought. Bots might not threaten livelihoods of writers any time soon (if ever), but there’s one thing I forgot to consider: how it feels to have a never-tiring, high-performing robot colleague.

A simple message conveying the bot we made together is doing great, and we should all strive to do better. Basic boss stuff, all good. But being a somewhat neurotic human specimen, I couldn’t help but take this deeply personal and have an intense emotional response.

Am I meant to compete with a bot now? Satoshi doesn’t need to sleep, feel inspired, or even have a drop of coffee to excel at his job. How am I ever supposed to catch up with that damned bot?

And some of my colleagues shared my worries: “I read this message whilst eating my cereal, it ruined it” and a simple, emotionally-charged “ugh.” While others didn’t mind because it frees us up for other stuff, “assuming we still have a job, of course.”

We probably don’t need to worry though, as bots will never reach human-level of creativity. But how will we feel working next to AIs? Probably a bit shit, to be honest.

It’s incredibly easy to anthropomorphize a bot that performs the same role as you, so when it becomes daddy’s — ehm, I mean the Editor-in-Chief’s — new favorite, it hurts. The comparison can also lead you to unconsciously start to shift your own goals.

What I want to do in my role could be summed up as writing good articles — an incredibly elusive and indefinable concept. I also like tinkering with phrases, coming up with clever little jokes, and making something that’s aesthetically pleasing to me. I also love it when an article I’m proud of gains a lot of traction and gets read by an insane amount of people — although that isn’t necessarily my main goal.

The problem with bots is that they have a singular, measurable goal — like pageviews — which makes me deeply uncomfortable. If I compare myself to the bot, the only thing I can compare myself to is the bots greatest quality, which is one of my secondary goals. Maximizing pageviews is the only goal this bot has, and can optimize ruthlessly for. And as Go, chess, and Starcraft 2 have shown, they excel at that.

Nonetheless, the more I think about it, the more I’m inclined to believe that the bot isn’t the villain, it’s metrics.

Don’t hate the player, hate the game

Bots are undeniably going to improve loads of fields as they’re far better at solving the tasks we set them up to do than we are. While this can include incredibly complex challenges, it always needs to be something highly optimizable — so where does that leave writing?

Journalism’s goal of finding hidden truths is hard to quantify — which is probably one of the reasons so many publications are failing. Being vague from a quantitative perspective means that the ‘metrics’ of journalism are difficult to stick a price on. And even harder for an AI to learn.

But the money has to come from somewhere, which means derivative metrics like pageviews are applied to measure overall success of publishing. Not in the least because eyeballs are what advertisers pay for, in the end.

One logical outcome of this was the flourishing of click farms, built only to churn out content that attracted clicks. As humans (and platforms) have wised up, however, this business model has taken some big hits. But what if content you originally had to pay humans to ‘write’ can suddenly be produced for almost zero cost by a bot? Bots can rise to the occasion.

They don’t need a salary, can’t unionize, don’t have paid time off, et cetera, et cetera, and I can go on and on. Which is exactly why my boss’ comment made me feel so uncomfortable. It leaves out the human factor (me! And my emotions!) completely. Is there no metric for how I feel?

The phrase du jour of technologists, ‘tech-minded’ CEOs, and other self-proclaimed thinkfluencers is that AI will actually make ‘work more human.’ The argument being that with the rise of AI, ‘soft skills’ like communication, creativity, teamwork, and problem solving will become the most valuable talents in the future job market.

But the truth is we’ve never fully known how to evaluate those skills — even before the Satoshi Nakabotos of the world started popping up. The struggle with finding a quantitative measure for journalism also applies to soft skills in general. How do we know if someone is great at problem solving? Maybe when their department manages to surpass their earnings target?

All the measurements we’ve come up with for job performances are incredibly rigid and don’t account for the multiplicity of the human experience — but great for bots. And even though you might get the freedom to create something cool, the fact is that everybody answers to somebody. What about the goals and responsibilities of your boss and your boss’ boss? What about the shareholders? What about the OKRs?!

Now, I could go on a full anti-capitalist marxist rant — but I’ll spare you the trouble. Bots are coming, there’s nothing we can do about it. We’ll probably feel like shit, because if bots set the bar, we might devalue our human traits that make us work well.

Hopefully we’ll actually get to a point where bots stay in their assigned supportive role, where it’s socially acceptable to not compare yourself to their output. But if we’re going to make work more human, we also need to find the human measurements to evaluate performance — and this will be the real challenge for society to overcome as tech progresses.

In the meantime, share this article as much as you can so I don’t lose my job to Satoshi Nakaboto.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.