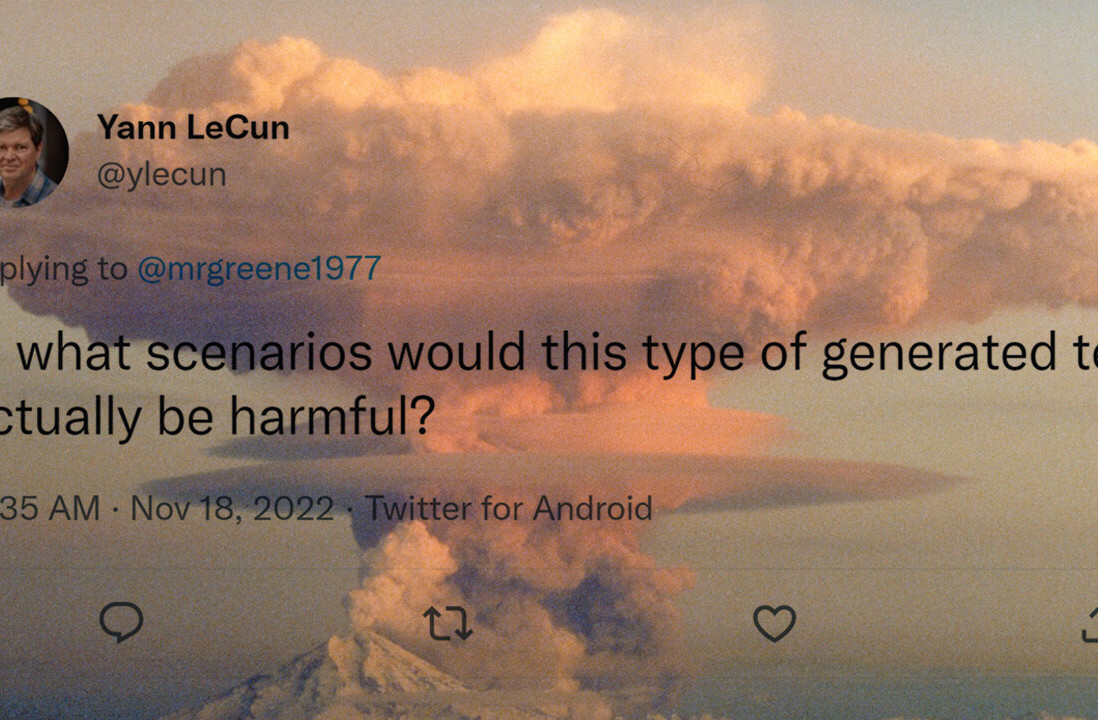

Faced with a potential crisis, the magnitude of which the world has never seen, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wants us all to slow down. Crises, however, wait for no one. And Facebook’s latest problem, that of altered or faked video, brings with it the democracy destroying power of an atom bomb.

“There is a question of whether deepfakes are actually just a completely different category of thing from normal false statements overall,” Zuckerberg told Harvard legal scholar Cass Sunstein at the Aspen Ideas Festival this week. “And I think there is a very good case that they are.”

Zuckerberg, of course, is talking about an artificial intelligence made popular on Reddit. In 2017, a Reddit user, u/deepfakes, posted a pornographic video featuring Daisy Ridley to the amazement of a crowd of voyeuristic onlookers. It was a fake. Later came additional erotic clips. There was Gal Gadot, Emma Watson, Katy Perry, Scarlett Johansson, and a handful of others, all looking as if they were performing in pornographic scenes. A short time later, u/deepfakes released the source code on GitHub, allowing other redditors to create and share their own video clips. The community was also integral in helping to fix bugs that made the videos less believable. The software improved so quickly, in fact, it became difficult to distinguish legitimate videos from those faked with the AI.

Take this video of Barack Obama, in which he refers to President Trump as a “dipshit.” It’s fake, of course, the product of a BuzzFeed collaboration with Academy Award-winning director Jordan Peele — who also voiced the clip.

Each of these deepfake videos is created using a machine learning algorithm, a smart AI that “learns” human facial expressions by studying a database of still images. From there it stitches together the images over an existing video, copying the facial expressions and applying them to the model to match its expressions.

Pop a few dozen photos into a database and you’re left with a flawed, but semi-passable fake. Add a few thousand photos from a public figure and the video becomes almost indistinguishable from the real deal.

There are subtle flaws, of course, dead giveaways to those who pay close attention or know what to look for. But the bulk of the population lacks the knowledge, the attention span, or perhaps the desire to make the differentiation. And it’s these stories that have a tendency to run amok, especially when they confirm longstanding biases. This same confirmation bias lead to fakes news stories outperforming real ones on Facebook in the run-up to the 2016 election, after all.

And therein lies the rub. The idea that your average consumer of news would be able to tell the difference between real and fake video, especially those clips that confirm their own biases, is absurd. Or perhaps they could tell the difference, but would that stop them from sharing it?

A recent fake, which isn’t a deepfake but a misleading edit, put this premise to the test. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi fell victim to a video edited to look as though she were slurring her words, perhaps the result of cognitive decline, or some other secret defect that made her unfit for office.

While BuzzFeed’s Obama video is clearly a fake, as referenced in the video itself, the Pelosi video was real. Or, it was before a Facebook user slowed it down and then uploaded it as if the video were authentic. By slowing the timing just a touch, the user who uploaded it managed to convince millions that Pelosi was suffering from some undiagnosed, or undisclosed, ailment — a trick that relied on the same playbook used by Trump and his cronies during the 2016 election in an attempt to prove Hillary Clinton suffered from a similar cognitive impairment.

This is problem number two, of many, for Facebook. While we can point to deepfake videos as outright falsehoods, edited clips like the Pelosi video are a bit harder to classify. Some, including Zuckerberg, would lump it in with interview footage where the uploader cuts or edits a video in a way to highlight out-of-context replies, or slips of the tongue in an effort to further an agenda.

If [our deepfake definition] is any video that is cut in a way that someone thinks is misleading, well, I know a lot of people who have done TV interviews that have been cut in ways they didn’t like, that they thought changed the definition or meaning of what they were trying to say. I think you want to make sure you are scoping this carefully enough that you’re not giving people the grounds or precedent to argue that the things they don’t like, or changed the meaning of somewhat of what they said in an interview, get taken down.

Edited video, whether created with AI or not, offers up a nightmare scenario for Zuckerberg and Facebook. For a company that has stated repeatedly it’s not in the media business, the future of news — hell, the future of democracy — may rest on its determination of newsworthiness and how it handles false or misleading information.

At the Aspen Ideas Festival, Zuckerberg says he and Facebook are working through this potential hellscape through its “policy process” — a process that, so far, has led to Facebook taking no formal action on the Pelosi video, or a deepfake mimicking Zuckerberg himself that was released days later.

“Is it AI-manipulated media or manipulated media using AI that makes someone say something they didn’t say,” Zuckerberg asked. “I think that’s probably a pretty reasonable definition.”

It’s a narrow definition, but one that Zuckerberg claims to be working on through internal systems. He noted the primary failure was one of “execution,” as it took the company’s systems “more than a day” to flag the video as potentially misleading. Though, even when flagged, it didn’t appear to offer much in the way of a definitive statement that the video was false, or otherwise misleading. Instead, users saw this, and only if they were in the US (based solely on what I saw on my own Facebook feed, as a journalist living in Mexico who viewed the video both with and without a VPN):

Facebook added a fact check pop-up to the fake Nancy Pelosi video. But this doesn’t seem to be the case outside the US, at least not where I live in Mexico. pic.twitter.com/ub2D5eu58E

— Bryan Clark (@bryanclark) May 25, 2019

The post shows that there is “additional reporting on this,” a shallow way to sidestep Facebook claims that it’s “tagging” misleading updates to better inform its users. If that is indeed the case, Facebook hoping to educate its users, there’s a noticeable omission of words like fake, false, or misleading within the text. To me, it reads as if outlets like the Associated Press are reporting the story, thus adding legitimacy to the claim.

Zuckerberg sees it differently. In his mind the problem is still in execution. Though outside fact-checkers confirmed the story was misleading inside of an hour after it was posted, its algorithmic systems took much longer. This isn’t good news for a company who hired fact-checkers who are fleeing en masse, stating that their job is less about truth and more about performing “crisis PR” for a company that’s desperately clinging to accountability.

In Zuckerberg’s vision, his algorithms catch the story within minutes, and then decrease the reach of the video by limiting its visibility to Facebook’s users. Unfortunately, this does little to keep people from seeing it. Facebook’s NewsFeed is designed, after all, to show content you’re likely to interact with. The only people who will see fewer of these stories are the types of people who don’t want to see them in the first place.

For Zuckerberg, this ultimately will come down a decision to continue placing his trust in AI and policy, or to allow humans to dictate what is and isn’t appropriate for the world’s largest social network. Or, there’s a third option: regulation. Facebook’s botched attempts at taking legitimate threats seriously, including those that may have swung a Presidential election in 2016, have led to renewed interest by congressional leaders to break up the company or to find better ways to regulate it.

Zuckerberg’s failure to take the problem seriously is perhaps best summed up in an additional quote from his recent appearance in Aspen. When asked about what Facebook was doing to prevent foreign interference in our next election, Zuckerberg opted to punt, stating it’s a problem that’s “above his pay grade.”

To date, it seems all of these problems have been above Zuckerberg’s pay grade.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.