Sunny Burns, an Australian man living in Thailand as an actor, fashion blogger and English teacher, had his life turned upside down in the hours following the bombing that took place in central Bangkok.

After CCTV unveiled surveillance footage of the suspect, it didn’t take long for the internet community to speculate the bomber’s identity. Tweeters and Facebookers encouraged people to submit photos taken in the vicinity around the time of the bombing for clues, only the Web to start its own hunt for possible suspects.

The guy in the picture doesn’t look Thai or Asian, more like a Westerner. http://t.co/wmCcd2XGzR

— Marvin H. Chow (@mchow1973) August 18, 2015

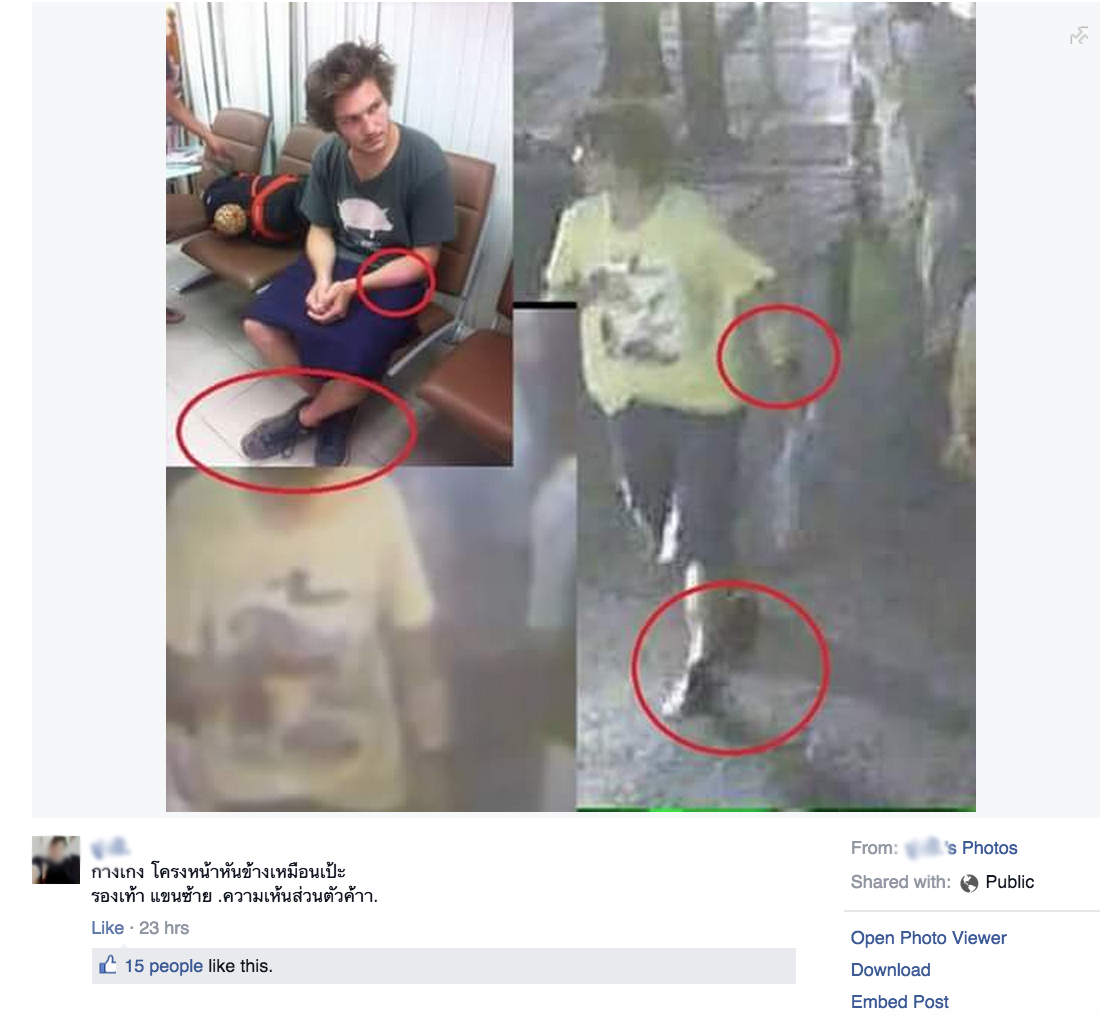

Which ultimately led to Burns’ photo being misidentified through various social media outlets. On his Facebook page, he writes:

“[M]any social media outlets released my photo in Thailand saying that I was a suspected terrorist as I looked like the suspect in question. All my private information from immigration was leaked online and people were looking for me – They even knew my home address.”

Burns eventually turned himself into the police, using Instagram to show his cooperation with Thai police. According to his Facebook update, authorities ended up searching Burns’ apartment for bombs.

I then had a number of death threats online and people asking me, “why did you do this to Thailand,” …. I used social media as a platform to protect myself and to let my family know where I was as I had no idea what was happening. I didn’t have phone credit to call my parents and the police couldn’t speak English. I was scared fucking shitless and was waiting for a translator. You have no idea about the trauma and how scared I was.

The situation is reminiscent of Reddit’s Find the Boston Bomber thread in which members used photographic evidence and recent news to pin their own terrorist suspects. In the rush, media sites wrongly accused a missing student of the act, further adding to his family’s grief.

Thinking before clicking

There are many perspectives on the effectiveness of internet activism. On one hand, the Web can be a great tool for relief efforts during disasters, such as the recent Nepal earthquake. A hashtag doesn’t mean you need to go lead a march for equality, especially if physical limitations are preventing you.

Yet, on the other, we have people changing their Facebook profile photos with a rainbow overlay and going back to watching cat videos. Hashtags and symbols are not a commodity; they are not meant to be used as a tool to pat yourself on the back for “taking part” in a revolution.

Internet activism is an extension of free speech and the right to petition – which means they should also be used responsibly. The United States protects you if you want to protest a homeless shelter being built in your neighborhood, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you should point fingers and abuse your right to opinions.

Hashtags can often cultivate much-needed discourse about race, gender and local policies. But it’s not enough to be engaging – you’ve got to find a way to be effective. By jumping too quickly to take part before the FOMO hits, you push the cause of online activism back five steps.

Read next: Meet the woman fighting Reddit racists by targeting the site’s advertisers

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.