“If someone here was a robot disguised as a human, who would it be?”

My coworkers and I play a game where we ask each other this question. Most go straight for the person who is the most efficient, most detail-oriented, and least emotional. I, on the other hand, have a different theory. Wouldn’t a scientist looking to humanize a bot attempt to create an AI system that appears least like a machine?

I search for the most irrational, most passionate, and most likeable — or unlikeable — person in the room. Maybe they’re the theoretical robot mole — that is, if the scientists are doing their jobs right.

The computational theory of mind, a philosophy that states that our brains are just computing machines, means we’re technically little more than robots anyway. So, what are the small details actually separating us from the machines?

According to Hooman Aghaebrahimi Samani, Assistant Professor at National Taipei University Robotics, and Elham Saadatian, a human-computer interaction specialist, it may just be chemical.

“The internal experience of love can be traced back to our endocrine system,” says Samani. “The way we feel about others is to a significant degree determined by hormones.”

But if love is just a recipe of pre-programmed hormones, does that mean we understand love about as well as Alexa?

The question of whether machines can truly possess emotional intelligence has been explored for decades. In the 1950s, Alan Turing, considered the grandfather of computers, posited a hypothetical test that could determine whether machines really do, in a sense, possess emotional intelligence that puts them on par with a human.

In essence, it’s not too far off from the game I played with my colleagues–in the test, a judge, not knowing if they are talking to a human or a machine, gets to type questions and receive answers. Based on those answers, they then have to guess if there is a human or a computer on the other side. It was once thought to be impossible that a machine would ever be able to “pass” the test by convincing the judge that it was a human.

But in 2014, a machine called Eugene Goostman beat Turing’s system, fooling a third of the judges — and not for the first time. Not only can machines pass the test that supposedly proves their humanity, but actual humans fail, sometimes being mistaken for machines.

Those results show that Samani and Saadatian, who theorized that the infrastructure of love is simply a hormonal mixture made up of estrogen, testosterone, and endorphins, are onto something. Maybe love really can be reduced into binary. Maybe it isn’t our hearts that draw us to the altar, but our anterior pituitary glands.

Besides, with virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) exploding into our small worlds, Snow Crash — the book that inspired the original VR world Second Life — reads like a prophecy instead of fiction, and Ready, Player One is its Part II. Let’s face it: reality is subjective, and it has been for decades.

Adding up the facts, the story doesn’t look good for humans hoping to claim an advantage over our robotic counterparts. Our brains are robots. Love is a concoction of hormones that can be digitally fed to robots. Robots are beating the Turing test, indicating their “humanity” while humans are failing, indicating their occasional lack of it. And the concept of “reality” is getting more and more blurry.

Ergo, we are robots and robots are us. The end?

Not quite. Yes, our brains are computers. Yes, mixed reality blurs the line. Yes, the same hormones that cause us to love can be digitally programmed into robots. Even morality is being programmed into robots, or at least the ability to make more moral choices using algorithms.

But what about programming something that can’t be drilled down into an algorithm, like a belief system, or faith in God? Robots, at least for now, can’t believe in God. Not don’t. Can’t. Humans can choose to believe in God, or choose not to. Operative word: choose. At least, we’d like to think so.

And if those choices and any others we make can seem absurd at times, perhaps that is exactly what gives us our humanity. After all, former Google and Microsoft software engineer David Auerbach once said that “absurdity is the mark of the human.”

Harsh.

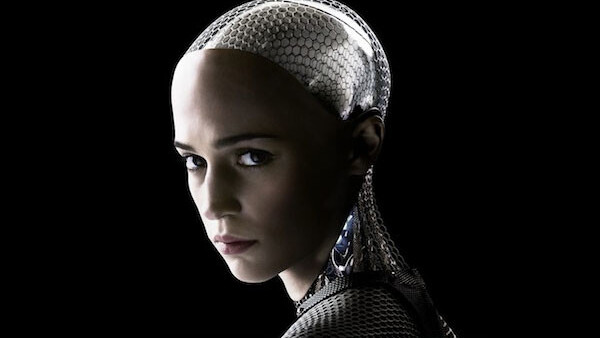

But he’s not wrong. People are absurd, especially in love. They love to torture themselves. In the popular science-fiction film Ex Machina, the human falls in love with the robot, while the robot? Not so much. So maybe the real test to determine humanity isn’t the Turing test; maybe it’s unrequited love. It’s our intention to be understood and our need to be loved that makes us human. We are ‘programmed’ to love because we are programmed to believe, to internalize, and at worst — to delude ourselves.

Perhaps, then, it really is our flaws — our errors in judgment, our illogical judgment, and our willingness to hold fast to love even when we get nothing in our return — that make us human. And If having flaws means I am human, I can live with that.

I would like to believe that all the people who didn’t love me back were really robots. At least I know this: since I’m the most likable (or unlikable) person at work, I’m not the mole. Or am I?

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.