In our recent interview with GetGlue CEO Alex Iskold, Alex made an interesting point comparing the Check-In gesture used by services like Foursquare, GetGlue, Meebo, SCVNGR, Gowalla, Fanvibe, Yahoo! Sportacular, Souljaworld, Miso, Facebook Places, and more, and the Like gesture, brought mainstream by Facebook and used by countless other social media services.

In our recent interview with GetGlue CEO Alex Iskold, Alex made an interesting point comparing the Check-In gesture used by services like Foursquare, GetGlue, Meebo, SCVNGR, Gowalla, Fanvibe, Yahoo! Sportacular, Souljaworld, Miso, Facebook Places, and more, and the Like gesture, brought mainstream by Facebook and used by countless other social media services.

From a business perspective, there’s a lot to appreciate about both Likes and Check-Ins.

Both are simple, one tap actions. Simplicity matters, as the simpler a publishing action is, the more people will do it.

And both gestures are capable of mapping products / places / objects to consumer or user preference.

Just as the neighborhood pizza place would love to know who its most frequent patrons are, so would Pizza Hut like to know a list of people who actively expressed liking their brand. Mapping this link between consumers and product is a crucial part of marketing.

To date, the Facebook championed “like” gesture has a massive lead in adoption. Like buttons are ubiquitous on photos, content, brand pages, media, and more.

But check-ins are on the rise.

Here’s why we think that 2011 could be the Year of the Check In.

In recent posts, we’ve hinted that we think that the check-in gesture has a future far beyond pins on a map. In this post we’ll look at some of the reasons why a check-in is preferable to a like, both to a user and a marketer.

Snapshots vs Permanent States

A subtle difference between the two gestures has to do with the concept of repeatability.

One of the things that has always bugged me about the like gesture is its permanence. Once you like something on Facebook, you can’t like it again. And unless you go through the clunky process of unliking that object, you are permanently associating yourself with it – whether it be a band, a celebrity, or a product. It’s almost like a bumper sticker or a tattoo – you better be damn sure about your permanent, ongoing affection for something before you place that endorsement on your car or body.

The check-in gesture has no such limitation.

A check-in is a snapshot, not a permanent state. On Last.FM, you can scrobble / check-in to the same song again and again. On GetGlue, you can check in to the same TV show over and over. On Foursquare, you can check-in to the same venue every day – indeed, regular check-ins like the office or a favorite coffee shop seem to be one of the most common sorts of behavior.

The repeatable nature of the check-in gesture is not only better for the user, it’s also better for the marketer.

The element of frequency is a crucial piece of information in determining a consumer’s affinity towards something. Indeed, frequency of attendance / consumption may even be a better indicator of liking something, than hitting a like button. You are what you do, not what you say.

I Don’t Like Everything

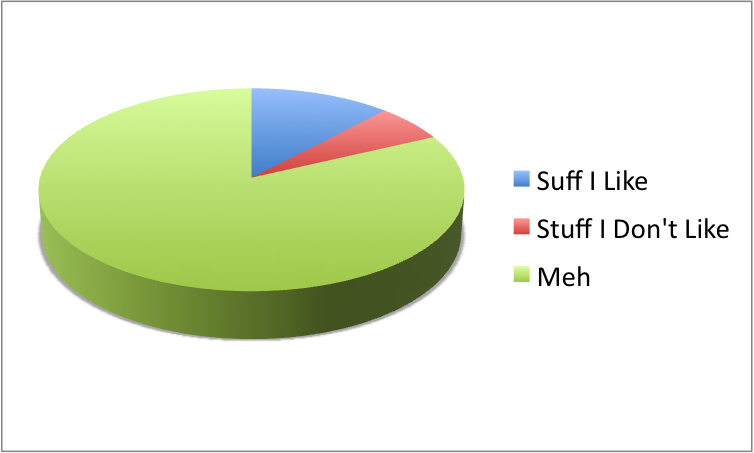

The world is made up of lots of different things. Things I like (Sublime, Sriracha hot sauce, and hoops), things I don’t like (eggplant, Nortena music), and lots of things I don’t have strong opinions about (chai, Atlanta) we’ll call this the Meh category. Here is a graphical illustration.

By limiting my content curation ability to only things that I like, Facebook is leaving a lot of news feed stories on the table (specifically, the Don’t Like and Meh categories), and is also leaving dark much of my product graph – the digital map that links me to products and brands.

Check-ins are not limited by the same contraints. I can just as easily check into a new restaurant that I end up not liking, as I can to a taqueria that I have been patronizing for ten years. With the check-in gesture, the connection is still made, and my presence or consumption noted. With the like gesture, that connection stays dark.

The Structured Status Update

At the end of the day, check-ins and likes have value in that they are able to communicate something meaningful in a structured fashion – affinity or present to a product, place, or thing – with minimal effort by the user.

If I want to tell the world that I like The Next Web, I have two primary options. I can click the “like” button on the TNW page on Facebook, or I can type the words “I like The Next Web” into Twitter.

On Twitter, my words are ephemeral. They will quickly wash down the stream, out of sight and out of mind. And even though other people are probably expressing their affinity for The Next Web via Twitter, it would be very difficult to match their sentiment with mine. Perhaps they used different words or word order, or spoke in a different language. This is the challenge of unstructured data.

But on Facebook, a hard link has been formed. TNW can now message me. Other readers can see my face in the sidebar as a fellow fan of TNW. A structured connection has been made that was easier for me to express (just one click!) than typing words into Twitter, and more valuable to The Next Web.

Foursquare was able to carve out a livelihood by taking a message that people like to share with their friends (their location), and making it easier, more useful, and more fun than typing words into Twitter.

Facebook’s like button is similar. It adds structure and ease to a behavior that was already occurring in social media – people expressing affinities for brands, products, and public figures.

But for once it seems that Facebook is not thinking big enough – its structured status update of choice, the like button, applies only to small subset of each user’s database of object interactions (aka stuff they encounter), leaving oxygen for the GetGlues, and Meebos, and Misos of the world.

Perhaps the most radically horizontal check-in service we’ve ever seen was a tiny New York based start-up called Hot Potato. They were so horizontal that you could check in to any verb, mad lib style, resulting in hilarious structured status updates like “Lawrence is going to bed with 27 others!”

Where are they now? Facebook bought them.

Whether or not Facebook decides to deprecate likes to check-ins, you heard it here first:

2011 will be the year of the check-in.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.