To pay or not to pay, that’s been the question since the very first moments of the App Store.

The question of whether or not to pay for software and exactly how much you should pay is far older than Apple’s App Store of course. The question stretches back to the early days of the BBS and shareware. But it’s become a hot topic yet again now that so many companies are looking for a way to consolidate customers into ‘app stores’.

Specifically I think it’s important to consider why paying for apps, regardless of where you purchase them, isn’t just a good thing, but something you should absolutely want to do.

Free is free.

One of the biggest misconceptions about free apps is that if the label in the App Store or on a website says ‘Free’ that there is no cost to you.

There is always a cost. Sometimes that cost is up front and clear-cut. This app costs $9.99. Great, pay your $10 bucks and move on with your day, enjoying your app.

Sometimes however, especially in the case of apps that are offered without a price, the cost is hidden. Instead of paying for the app up front you may pay for it in one of many other ways over the course of using the app. The developer of a free app has several avenues of making money provided to them by Apple including in-app purchases and of course, advertising.

Let’s set aside in-app purchases for the moment because that does shift back to a discussion of fixed monetary cost. Instead, let’s talk about the ways that a user pays for an app that’s delivered to them free in an ad-supported model.

Take the recently hot Twitter app Tweetbot as an example. Tweetbot is currently offered at a $1.99 price point on the App Store, a price that seems like a huge luxury when the official Twitter app is free and offers very similar basic functionality.

All of those reasons why you wouldn’t pay for another Twitter client when the one you have is working fine just melt away once you start using Tweetbot’s clever crafted-with-care interface. Not only are many common Twitter tasks easier to do but the app is also much more satisfying to use than most Twitter clients. I asked Tweetbot co-creator Paul Haddad about why they chose not to go ad-supported in the already crowded Twitter client market

Paul was forthright about the fact that the designs of any of their apps simply wouldn’t work in an ad supported form, “None of our previous apps would work with an ad model,” Paul told me, “and I think for us it might cheapen the brand.”

The concept of keeping the aesthetic of an app and a brand clear of advertising isn’t new of course, but it’s becoming less common as the App Store shifts towards apps that are offered free as the developers hope that embedding ads in some portion of the app’s UI will deliver enough revenue to support it’s growth.

It would seem like the costs of advertising would be effectively zero for the user but a glance at many of the ad supported apps on the App Store shows that there is a huge cost in terms of aesthetics and usability. In order for ads to be displayed in portions of the app that users will be guaranteed to see and interact with, it’s hard to maintain the cohesiveness and integrity of your app.

You only have to look at the recent inclusion of the universally reviled ad bar across the top of the official Twitter app. Annoying and crass, it was quickly dubbed the #dickbar by the Twitter community and subsequently removed from the app by Twitter.

Haddad and his partner Mark Jardine run Tapbots as a two-man operation, aiming to produce apps of quality in a hands-on process rather than expanding to a larger team that wouldn’t maintain the same level of focus. Thanks to the fact that they charge for their apps, rather than rely on finicky revenue from ads, they’ve been able to do that.

“We’ve been profitable since day one,” Haddad says, “and have purposefully planned not to grow so that we can keep our quality as high as possible. That’s probably not the answer you normally get but I don’t think we’re a normal company either. We’re looking to push the envelope on the platform, have fun and pay the bills, not become the next Microsoft [or] Apple.”

This boutique app mentality isn’t unique to Tapbots either. It’s an avenue that more and more developers are pursuing as they try to serve a customer base that wants to invest in an app’s ability to serve them, rather than just pump out whatever piece of software is hot at the moment and move on to another project when interest fades.

Investing in apps.

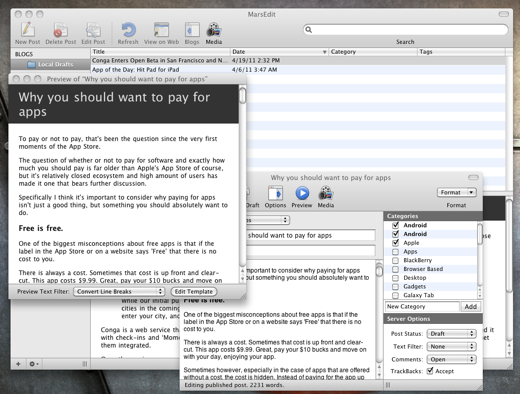

A veteran of Mac application development, Daniel Jalkut has plenty of thoughts about pricing and software. He’s the author of MarsEdit, a perennially popular offline blogging tool that has a cult-like following among many prolific bloggers.

MarsEdit is available for download via the Mac App Store or from Jalkut’s Red Sweater Software. You can grab a free version to try out the app and then purchase the full version for $39.99 after you’ve had a chance to check it out. I tried out MarsEdit after hearing about it for years and purchased it after a single day of use.

My snap decision to purchase MarsEdit has been rewarded with hours of time saved and many thousands of words typed and published with the tool. Using it for even a few minutes gives you the sense that someone has generally listened to requests from users and acted on them conscientiously.

I spoke to Jalkut in preparation for this article and my initial questions were about the way that charging for MarsEdit has allowed him to build his business as a small indie developer without funding from investors. He acknowledged that setting the correct pricing and collecting payment for his app was important but said that a feeling of investment in an apps success was even more instrumental in the success of MarsEdit.

“I would like to take a slightly different tack and point out that I think it’s important to give customers the *opportunity* to invest in the livelihood of a product,” stated Jalkut, “I have found that pride of ownership is one of the most important things I can give to a customer, and without a reasonable price attached to that, I don’t think the pride would be as high.”

Taking pride in the way that a tool works for you isn’t limited to paid apps, there are many examples of fantastic free apps on the App Store for instance. “But,” Jalkut says, “I believe that something important clicks when they have spent hard-earned money to help support the tools that they use.”

He drew an interesting parallel in our discussion, one that stuck a chord with me. “You’ll take more pride in the car you saved for and bought, than the hand-me-down from parents or another relative.”

As a car enthusiast and tuner I’ve spent countless hours tweaking, polishing and modifying cars to get them ready for car shows or simply just to do it and I can attest to the pride you feel after investing your time and effort into a vehicle. I would venture to say that this investment goes both ways when it comes to apps.

If you invest your hard-earned money for an app, you deserve to open and use it and feel that same investment back from the developer. If you do get that feeling, that someone else has put their time, effort and care into making the app that your’e using, your investment is rewarded and you’re more likely to use the app’s capabilities fully.

Once that investment has been made on both sides, there is more likely to be a connection made between app and user. As Jalkut says, “They are not only likely to be more committed to exploring the app, but are more likely to be passionate in describing the app to friends, sharing news of the app with followers on Twitter, etc.”

However, as I touched on before, just because many of the truly fantastic apps on the App Store are paid apps doesn’t meant that you can’t find honest and meaningful products that are offered for free.

Not many apps have had the chance to enter the App Store as a free app and then gain enough love and promotion from the community to then re-launch as a premium paid app. SoundHound is one such app and their success on the App Store and the Android Market are a testament to the power of a well-built app.

Free to paid and back again.

SoundHound is a music identification app that began it’s life on the App Store as the free app Midomi. Soundhound is now available as a paid app and a free, feature limited, app on the Android Market and iOS App Store.

SoundHound gained popularity in the mobile space by being extremely quick about identifying songs and offering users the ability to hum or sing the songs that they’re trying to ID if they didn’t have an audio sample. The extensive feature set as well as a fantastic conversion rate of people that try out the free version of the app and then purchase the paid version made SoundHound the number one paid iPad app of all time earlier this year.

I asked SoundHound VP Katie McMahon about the beginnings of the app as a free tool. In 2009, we made the decision to change the model to a “paid app” for several reasons, ” McMahon said, stating among those that they needed additional revenue stream to grow the company. That increased revenue stream allowed SoundHound to achieve the goals of being the fastest music discovery app on the market.

That speed, enabled by their switch to a paid app, was directly related to the continued success of SoundHound when compared to other applications in the same space.

SoundHound is now available as both a free introductory app and a full-featured paid version, which runs $4.99 on both the Android Market and the App Store.

McMahon intimated that this flexibility was important as it allowed them to leverage the income of the paid version to fund company growth and the marketing power of the free version to show people the benefit of the paid app.

If SoundHound had continued along as the free app Midomi, they may have continued to grow at least slowly, at an ad supported speed. But charging a fair price for their app allowed them to grow and add new features. Features that made a huge difference for the company in a crowded market and features that continue to benefit users looking to see who sings ‘that song’.

Making good apps is tough, supporting them is important.

If there’s anything to take away from this discussion it’s that making apps that are truly engaging, feature rich and make you feel invested is a difficult proposition. Having the ability to charge for those apps fairly gives small and large developers the ability to enhance the apps, bring better features to the user and at a very basic level, simply continue making them.

In chatting with Haddad of Tapbots we touched on the fact that Twitter had recently implied that making any more Twitter clients was a waste of time for developers as there were plenty on the market.

“I do agree with them that its going to be very hard for anyone to make a competing client on any of the platforms Twitter currently supports,” says Haddad and he’s correct, there are dozens of free apps that access Twitter in at least a basic fashion, including Twitter’s own official client.

Free apps shouldn’t be looked on as evil by any means. There are tons of single-use utility apps and fun if briefly diverting games that are offered free on the App Store and that are pretty great.

But if you like well crafted and truly useful apps that make you want to use them, there’s a good chance that there is going to be a dedicated developer or team of developers behind that app that are going to need the money that you pay for their app to keep making them better.

As for the future of Tweetbot? “I’ve seen a few high profile twitter employee tweeting with it,” says Haddad, “and we’ve gotten complements from many of them. It’s hard to compete with apps that are both good and free. It can be done but you really need to have your act together to do it and its very high risk.”

The upside of that risk is that as long as developers can make a product that’s good enough to charge for and people continue making the investment in those products, we’ll keep seeing truly fantastic apps.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.